Getting married is an important decision that deserves a lot of careful thought—after all, it’s a promise to share a lifetime together, for better or worse.

For one Redditor, however, a recent and rather unusual experience forced him to reconsider whether his fiancée was truly the right match. During an unexpected house fire, she lost her composure and was quickly overtaken by panic and fear.

And just like that, he began wondering if she was really ‘wife material’ after all.

During an unexpected house fire, the man’s fiancée lost her composure, quickly overtaken by panic and fear

Image credits: Skylar Kang / pexels (not the actual photo)

And just like that, he found himself wondering if she was really ‘wife material’ after all

Image credits: Levi Damasceno / pexels (not the actual photo)

Image credits: Alena Darmel / pexels (not the actual photo)

Image credits: TrickyInteractions

Why we react the way we do during emergencies

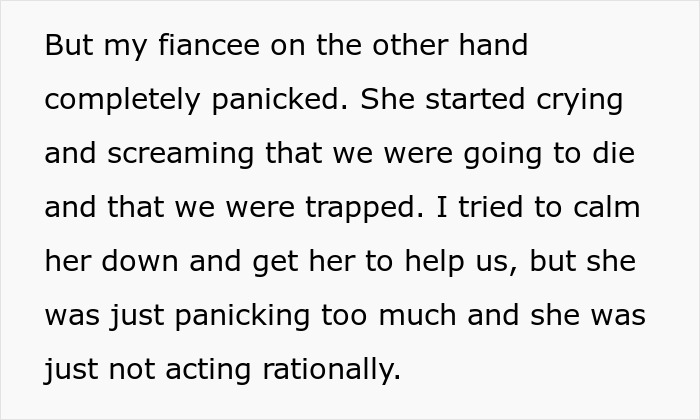

We can’t always predict how we’ll react in a crisis—whether it’s a friend choking at dinner or an earthquake shaking the city. Some people spring into action, some are gripped by panic like OP’s fiancée, while others might freeze altogether.

But what is it that makes our responses so different? Innovation advisor Russell Shilling, who has served as the American Psychological Association’s chief scientific officer and was a Navy aerospace experimental psychologist, shares some insights on the topic in a conversation with Fast Company.

According to Shilling, our reactions to danger are shaped by our past experiences and what we perceive as threats. “If you’re primed to be afraid of flying, you’re more likely to have a strong reaction to things going on in an airplane, such as turbulence,” he says. But in a situation such as a fire, your response could take on another form entirely.

When people freeze in an emergency, it’s often because they’re stuck in fight-or-flight mode. “You’re trying to find a plan on how to react,” but thinking clearly becomes difficult as the limbic system isn’t functioning properly. “You basically look like you’re freezing, but your mind is trying to plan your way through it,” Shilling explains.

This is is actually considered one of the most natural and common ways people behave. During a stabbing incident on London Bridge in the UK, for example, an off-duty police officer who tackled the attackers recalled that many bystanders were standing still, like “deer in the headlights.”

However, the good news is, it’s possible to teach yourself to stay calmer under pressure. Although it’s not easy, training can help replace automatic, unhelpful responses with actions that could save your life. “If you’ve been heavily trained, you’ve already got a set of responses that you’re ready to use, so you don’t have to spend a lot of that time [thinking about what to do]. Your training kicks in,” says Shilling.

For instance, whenever Shilling attends a large event with his family, they discuss and set up an emergency plan so everyone knows what to expect. This includes locating exits, noting the crowd size, and avoiding unnecessary anxiety.

Training and preparation, Shilling says, “can give [us] a sense of control.” It’s hard to say how we’ll act in a tough moment, but we can practice responses that’ll help us stay grounded if we ever need them.

Image credits: MART PRODUCTION / pexels (not the actual photo)

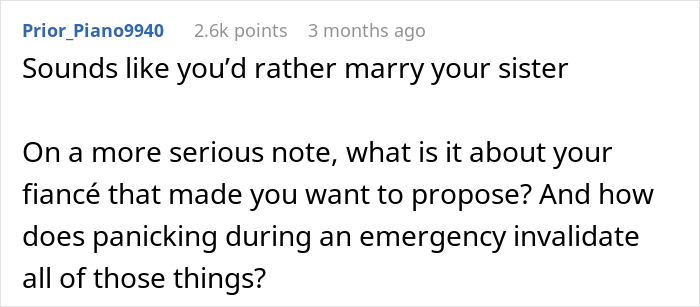

Commenters encouraged him to break up—not for his sake, but for hers

One user chimed in with a personal story, reminding everyone that it’s hard to predict how any of us will react in a crisis