One of the most important duties of a restaurant manager or owner is maintaining an effective shift schedule. However, not all of them are capable of it.

Some time ago, Reddit user Cartelans was working as a line cook at a fancy establishment. In a post on r/antiwork, he said it was run by a woman who was “fabulously wealthy” and “very out of touch with reality.” Quite the combination. As you might guess, it meant there was enough chaos in the kitchen.

So when the time came for the cook to take his pre-planned and long-awaited mini holiday, he couldn’t be happier to go away with his wife. But little did he know that his boss would demand he cancel it due to insufficient manpower for the upcoming weekend!

On-call schedules introduce a lot of uncertainty to an employee’s life

Image credits: cottonbro studio (Not the actual photo)

And as this story shows, at a certain point, enough is enough

Image credits: ckstockphoto (Not the actual photo)

Image credits: Cartelans

People need to have at least some guarantees

In many restaurants, on-call scheduling is pretty much unavoidable. That being said, it still needs to be handled in a way that respects employees’ time.

In recent decades, many companies have acquired sophisticated programs that track employee hours in 15-minute increments and help managers make scheduling decisions.

However, the use of such software echoes the trend of just-in-time manufacturing. And when a company applies principles developed for supply chains to its labor force, the result can be a mess.

“You’re waiting on your job to control your life,” Jannette Navarro, who was a Starbucks employee in San Diego, told The New York Times. She would get her week’s schedule just three days in advance and said that Starbucks software often determined everything from how much sleep her son would get to “what groceries I’ll be able to buy this month.” (It’s worth mentioning that Starbucks did change its scheduling policies after the Times article was published.)

Sadly, “From an employment law perspective, scheduling is pretty much unregulated,” said Charlotte Alexander, a legal scholar at Georgia State University.

For example, in some places, if workers report for their scheduled shift and then are sent home without pay, they are to be paid a minimum amount — usually between two and four hours of work. But if an employer simply refuses to make a schedule until shortly before a shift starts, policies do not apply.

Alexander worries that beefing up some of the existing worker protections, which take schedules as a given, will push employers to rely solely on a fully on-demand model in which workers don’t learn if they have work until the very last minute. “I would be afraid about nudging employers any closer to an all-contractor, all-temp world than they’re already going,” she explained.

Instead, Alexander argues, the law should directly regulate scheduling. For instance, the law could require employers to provide employees with their schedules a minimum number of days ahead of time. Employers that failed to provide sufficient notice — or who canceled shifts at the last moment — would be required to pay workers extra to compensate them for the inconvenience of, say, having to cancel their getaway.

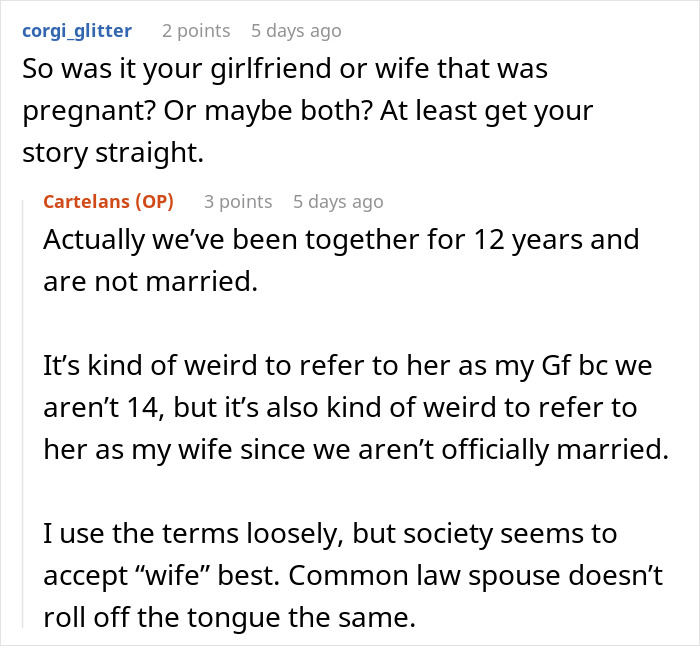

As his story went viral, its author clarified a few things in the comments

And it has received a wide range of reactions