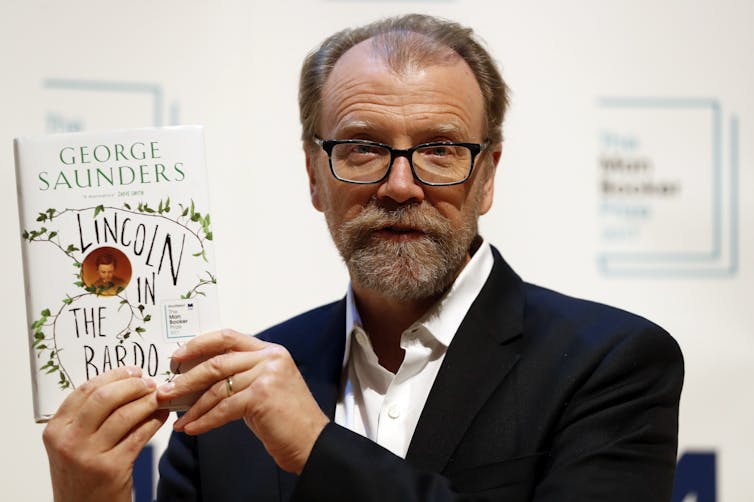

George Saunders is best known for his only novel to date, the Booker Prize winner and New York Times bestseller Lincoln in the Bardo. But he has long been celebrated for his innovative short fiction, which has won him a litany of prestigious awards and fellowships. In 2013, Time Magazine ranked him among the world’s 100 most influential people. The publicity for his new short story collection Liberation Day pummels you with praise of his literary powers: he is “masterful”, “the best short-story writer in English”, and so on.

Review: Liberation Day – George Saunders (Bloomsbury).

The “master” label sits awkwardly with Liberation Day’s interest in various forms of enslavement and entrapment. It is hardly one Saunders would embrace, judging by the humility of his interviews and his advice to aspiring authors in A Swim in the Pond in the Rain (2021), a book based on a course he teaches at Syracuse University, in which he outsources a wonderfully self-effacing “Master Class on Writing” to the 19th century short-story specialist Anton Chekhov, along with Chekhov’s fellow Russian writers Gogol, Tolstoy and Turgenev.

Saunders studied at Syracuse, where he was mentored by Tobias Wolff, but his first degree was in geophysical engineering. He worked for over 15 years in oil exploration and related fields before coming late to writing. This unconventional background, he contends, shows in some of the quirks of his prose: “Like if you put a welder to designing dresses.”

It may also help to explain his genre-bending tendencies. Saunders is not usually described as a science-fiction writer, but his short story CommComm won the World Fantasy Award, and several stories in Liberation Day could be classified as speculative fiction.

The “bardo” in the title of Lincoln in the Bardo refers to a state of limbo between death and rebirth in Tibetan Buddhism, reflecting Saunders’ own Buddhist leanings. The nine stories collected in Liberation Day, five of which were previously published, are likewise concerned with intermediate states. Characters are stranded between life and death, between personhood and thinghood.

Drilling aslant into questions of national identity, the stories are also linked by themes of complacency and resistance, the banality of evil, sins of self-preservation, cruelty as a social lubricant, and the collateral damage of unexamined lives. Saunders somehow marries postmodern irony with moral seriousness. He can wrap an emotional gut-punch in a belly laugh.

Read more: In The Candy House, Jennifer Egan delivers an inventive novel for a digital age

Scraped and enslaved

The lengthy title story, which opens the collection, is sublime: a deft, hilarious and terrifying feat of world-building that makes the words “tragic”, “absurd” and “inventive” feel inadequate. The story is itself concerned with the power of words. Readers must quickly adjust to the strange language of a first-person narrator whose cognition is simultaneously impaired and enhanced by artificial means.

Jeremy, it emerges, is one of four human “Speakers”, who are mentally “scraped” and enslaved by one Mr Untermeyer, or “Mr U”. They are programmed by a “Mod” to give oral recitals on different topics for “Company” (house guests). These recitals can be adjusted for “Intensity” and “Specificity”. The Speakers are literally fixed in place (“Pinioned”) on a wall, with minimal concessions to ergonomics:

Jed Dillon arrives to administer the Required Inter-Pose Stretching. Or, as he says it, “for to Stretch y’all.”

Stretching, after nine days in the shape of the letter X feels, as one might imagine, both good and bad.

If this excerpt fails to intrigue, the story may not be for you. Caveat lector: this is not science fiction, as such. Saunders is uninterested in the logistics of how a “Mod” would work, or the science of “scraping”. Rather, the focus is on the individual and group psychology of the scenario, the manipulations involved, the moral and political blindness.

Neither is it realism, although the improbabilities of the story are deeply and horribly connected to the now and the possible. Our gradual surmise is that Jeremy signed up for “scraping” due to economic hardship. This is not so far removed from the realities of paid medical trials exploiting the disenfranchised and uninsured accident victims begging bystanders not to call an ambulance as they bleed out.

Saunders earths his darkest flights of fancy with moments of jarring mundanity – the Speakers’ new uniform sweatshirts arrive in a Target box – and through the Untermeyer family’s naturalistic dialogue, as when “adult son Mike” scorns his father:

Fine, Dad […] Have fun with your “show”. Have fun choreographing your reactionary History Channel bullshit.

Mr U. (read: USA) then cynically purchases a data upgrade for the Mod to add “the Indigenous perspective” to his Speakers’ account of Custer’s Last Stand. The rapt passivity of the Company calls attention to how far our habits of speech and attention are already automated, and how much of our politics – even protest – is puppetry.

Saunders’ interest in such quandaries is evident throughout his work, from his first non-fiction collection The Braindead Megaphone to the wonderfully prescient fable My Flamboyant Grandson (2002), in which pedestrians encounter different versions of downtown Manhattan based on their personal purchasing and viewing histories.

During rehearsals, Mr U. instructs his dehumanised slaves to move out among Company and make them “understand that this thing actually happened, it involved real people”. Then actual violence intrudes, compounding the ironies and adding nuance to the tale’s politics. The siege is no longer a mere story. Saunders ingeniously orchestrates this convergence through the crossed wires of the narrator’s modified consciousness: “The prairie grass sways. Among the folding chairs.”

As Custer’s men rope the hands of widowed First Nations women, faint memories of Jeremy’s wife and family surface. When Jeremy assists in his own recapture, his inner conflict maps onto national divisions with gripping immediacy. It is not that one predicament is a stand-in for another; multiple layers of allegory and critique are going on at once – and we, as Saunders’ audience, are as problematically rapt in his story as Company are rapt in the Speakers’.

Further complexity arises from a subplot involving a warped romance between the narrator and Mrs Untermeyer, who has secretly set the Mod so that Jeremy will sweet-talk her. This is a curious take on the Orwellian question of how far thought is determined by language. “Speaking of her Beauty so often, with such high Specificity, made her Beauty real to me,” Jeremy explains. His curious idiom flowers in these romantic passages, as when he describes Mrs U. “smelling good, like a rose, if a rose were a bit angry”.

Read more: Ghoulishness, depravity and stupidity: welcome to the world of Ottessa Moshfegh's Lapvona

Limitations

It was actually a relief that the balance of the collection was not nearly so good as this opening story; the pity and terror of its tragicomic catharsis left me almost unable to read on. A couple of the other stories fit Saunders’ description of a good short story as “a thrill-producing machine”. Others, like My House and A Thing at Work, feel more like filler, though they do bring out some of the sub-themes and contemporary resonances of the more adventurous pieces.

Unfortunately, they also show up some limitations. I might, for instance, have been less conscious of the way the title story indulges tired stereotypes of middle-aged female vanity had this been balanced out in other stories in the collection. Instead, my concerns deepened.

In The Mom of Bold Action – the first of two stories with mothers in their titles – the protagonist is a (possibly unpublished) children’s book author, who is, as New Yorker editor Deborah Triesman points out, “used to anthropomorphizing everything around her”, from can openers to dog treats.

Yet she fails to extend human recognition to “two old hippies”, one of whom may have attacked her son. Her delusions of literary grandeur are skewered with crude ironies when she dashes off a self-righteous diatribe denying the hippies’ right to due process. She immediately dubs herself “an essayist” and assumes that her husband has taken up running because

reading her essay made him want to be as good at something as she was at writing. Not to brag.

The story’s title is one this “mom” bestows on herself. But as things go wrong, she becomes aware that she “could do more good in the world by, like, baking”. There is every indication that her essay is dreadful, both as literature and ethically, so the story might seem to endorse this “get back to the kitchen” message.

If you dislike The Mom of Bold Action, you’ll loathe Mother’s Day, in which the central complication is the rivalry of two vain and self-absorbed female characters over a man. Following a fairly trite vision of herself encountering saints in heaven, the mother character, Debi, congratulates herself:

The creative mind, wow. Especially hers.

Debi blames her child for her maternal failings, deciding that “somehow she’d gotten stuck with the wrong kid”. She resentfully recalls an occasion when her daughter refused to eat a mac and cheese she made with strawberry yoghurt instead of milk, because she’d been “a little distracted” by one of her lovers (“Phil, or maybe it was Clive”) and “hadn’t been to the store in a week or two”. In an imagined dialogue with her daughter, Debi concedes “there are too many men in my life”, then sarcastically resolves to “start saying no to life” and conforming to the mould of “Perfect Robotic Mother”.

Why does Saunders repeatedly undermine the idea of mothers making space for their desires or creative aspirations by presenting it through such caricatures? In both “bad mom” stories, there are startling swerves in the women’s thinking – fledgling moments of insight or self-awareness, apparently designed to introduce nuance and moral complexity – but they feel like too little too late.

Feminist attitudes are discredited again in A Thing at Work, in which the snobbish Gen films a working-class female colleague stealing paper towels from the office kitchen. When their supervisor quite reasonably questions Gen’s motives, Gen thinks:

What offensive questions! Would he have asked those of a man?

Yet her mockery of the “stout middle-aged chick stealing” is blatantly sexist. Later, Gen cynically plays the gender card to excuse her own misconduct, blaming “the insecurity of being a woman in a working world dominated by men, and also some stuff from her childhood, with her mom”. My emphasis.

Saunders’ characters are, as Triesman notes, often “comically limited in their thinking”, but it sours the collection that while focal male characters tend to be constrained by outside forces, the weaknesses of their female counterparts seem inherent (or home-grown, at least). The most sympathetic female character in Liberation Day is the young woman at the centre of Sparrow, a rather sweet heterosexual romance. She lacks any personal opinions and is “experienced by most people as a slightly puzzling blankness”.

Given Saunders’ outspoken opposition to macho writers and his urging of tenderness and generosity, one can only assume the bias is inadvertent.

Read more: Feminist stories and dangerous bodies: Siri Hustvedt in conversation with Julienne van Loon

Dystopian imaginings

I thought Saunders would not come close to equalling the opening story until I reached the tear-jerker Elliott Spencer, which belongs to the same speculative universe. Like the collection’s title story, it features a “scraped” narrator – this one is a former transient in his late seventies, who is part of a group being trained by their (implicitly) right-wing handlers to bellow insults at political rallies. There are indirect parallels with the way Saunders has written about the rise of Trump, which this collection also tackles in Love Letter.

Elliott Spencer begins with a vocabulary lesson. We are introduced to familiar words as if to a foreign language, so that they are made strange. The narrator recalls Jeremy from the title story in his naive devotion to his condescending captor, also apparently named Jeremy.

The prose is physically fragmented and spaced on the page so readers can see, typographically, the narrator’s shattered subjectivity and the difficulty he has connecting thoughts: “Jer who in early times my brain so blankslate all I could say was blegblegbleg taught me word upon word […] with his sometimes macaroni breath”.

When the narrator is attacked by his captors’ opponents, memories of a past mugging resurface, bringing back remnants of his former identity: “Elliott Spencer, under bridge Just like snap his money he got from returning shit ton of empties Is gone ”.

These italics are not for words new to his post-scrape vocabulary, but words recovered from his old life. In a passage of unbearable beauty and sadness, childhood memories also begin to return (with a nod to Citizen Kane’s “rosebud”). At the story’s wrenching conclusion, as Elliot makes a momentous decision, the remnants of his fallen self take on the gleam of something precious, even magnificent.

Along the way, there are moments of comic relief. Saunders’ dystopian imaginings often generate humour through incongruous specifics. In the post-apocalyptic story “Ghoul”, for example, the narrator is employed as “Squatting Ghoul Eight” in an underground amusement park with no sense of what lies above ground. His lunch consists of “a broth with, plopped down in it, a single gleaming Kit Kat”.

To the extent that the stories in Liberation Day blend “bizarre fantasy and brutal reality” (as the blurb promises), the former is always in service of the latter. Where they beggar belief, it is usually to deepen understanding. Saunders has admitted that he “used to look down on those floppy verbose novelists”, only to join their ranks. But the best stories in this hit-and-miss collection suggest we should stop looking for the Great American Novel: Saunders can do in one page what Jonathan Franzen cannot in 500. He digs so deep that, like the eponymous narrator of Ghoul, you may be left gaping: “What next?”

Sascha Morrell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.