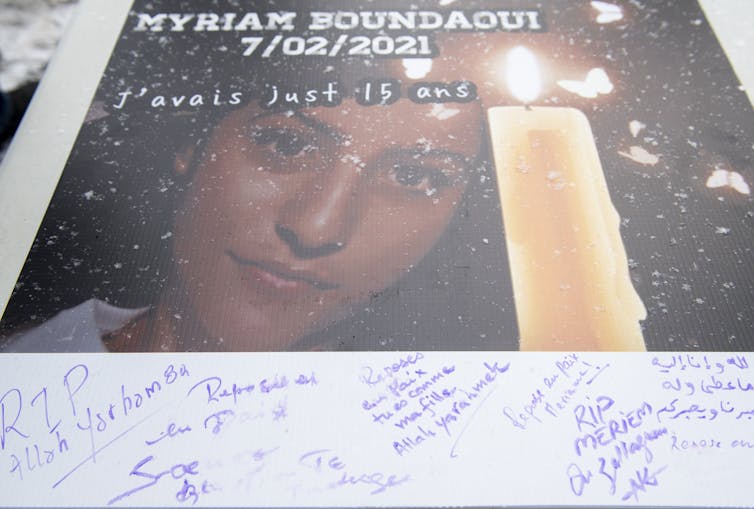

Canada has seen an increase in gun violence in recent years. In the past few months, Montréal and its suburbs have seen numerous shootings, with some fatalities, including bystanders. There have also been several shootings near Vancouver and Toronto.

In 2020, there were 277 firearm homicides in Canada, the highest number since 1991. It goes without saying that some sort of intervention is required to resolve a problem that has become costly and damaging for society, not to mention the victims and their loved ones.

At the moment, however, the only strategies that politicians and law enforcement agencies are suggesting involve increasing the number of police officers or crackdowns. This leaves me puzzled. Both my research on the issue of criminal networks and the scientific literature suggest there are other, more effective ways to address this problem.

À lire aussi : La prévention est le moyen le plus efficace de réduire la violence armée

Problem-oriented policing

Do more police translate into less violence? Not according to a systematic review of studies that have examined the issue.

While an increase in police resources is shown to have, at best, a small effect on crime in general, it has not been found to have a specific impact on violent crime. Moreover, these policing strategies create social tensions and discriminatory processes and increase the risks of victimization, all of which work against a comprehensive solution.

In addition to being fairly ineffective, these strategies are inefficient and represent considerable costs to taxpayers.

But we can learn from other innovative strategies that have been implemented elsewhere in the world. Although not widely implemented in Canada to date, these solutions, based on problem-oriented policing, promise better results in combating gun violence.

Targeting the problem at the source

Rather than simply reacting to each event, as is currently the case with gun violence, problem-oriented policing, as the name suggests, promotes a proactive approach to crime, targeting the problem at its source.

Specifically, the strategy focuses on deterrence. This strategy specifically targets individuals or groups at risk of committing violent acts, and aims to deter violent behaviours by leveraging the threat of punishments and the potential benefits of abstaining from violent acts.

In concrete terms, interventions based on focused deterrence involve both police services and community representatives who collaborate to initiate a discussion with individuals at high risk of becoming involved in violent crime. The purpose of this discussion is to communicate clear incentives to avoid violence, and disincentives to engage in it.

Incentives and deterrents

Once targeted, offenders are provided with information about the availability of various services in their community. Incentives include employment assistance, psycho-social intervention, training and community support programs.

Elements of deterrence are also invoked: the individuals we meet are informed of the increased legal sanctions that they and their associates will face if they continue to commit violent acts. This increased punishment may be specific to violent acts, but it may also be extended to other, less serious offences. For example, if a gang increases its level of violence, more attention may be placed globally on the group’s drug trafficking activities.

Beyond a simple carrot-and-stick strategy, focused deterrence initiatives aim to reduce the opportunities for individuals to commit violent acts, make the local community a partner in the process and improve the relationship between law enforcement and the community.

The group rather than the individual

These programs can take many forms, but the most effective is based on the Operation Ceasefire model introduced in Boston in the 1990s.

This violence-reduction strategy targets gangs as groups, rather than as individuals. In these programs, justice, social services and community organizers are encouraged to engage directly with violent groups, to express moral and legal concerns about the violence they have experienced, to offer sincere assistance to those who want it and to implement strategic law enforcement campaigns against those who continue their violent behaviour.

These strategies have shown very encouraging results. A systematic review of 24 studies evaluating programs of this nature concluded that they had significant effects on reducing gun violence.

For example, in one of our studies, we found that the implementation of such a program in New Haven, Conn., reduced gun violence committed by gangs by 73 per cent. In addition, through the process of information dissemination among members of criminal groups, associates of the individuals encountered in these programs also obtained benefits from these interventions.

This observed decrease is much more effective and efficient than simply increasing the number of police officers working without an overall strategy aimed at the cause of the problem, or one which does not involve community members.

To our knowledge, there is no such intervention strategy in Québec. The Québec government has announced $2 million in prevention projects in seven Montréal boroughs, such as upgrading sports and cultural facilities. But repressive strategies received more than double the investment of those focused on prevention.

There is no good reason not to implement these kinds of programs, which have been proven successful elsewhere in the world. It is time to think about the issue of gun violence in a comprehensive way, in terms of prevention, rather than just through reactive and strictly repressive measures.

Yanick Charette has received funding from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.