To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognised need of the human soul.

So claimed the great French philosopher, activist and spiritual writer, Simone Weil, in her classic 1943 book, The Need for Roots. It was published months before her death in England during some of the darkest days of German occupation of her homeland.

Eighty years later, this question of the vital need for people to have a sense of rootedness within communities, bringing meaning and a sense of worth to their lives and endeavours, is as urgent as ever.

An extraordinary, paradoxical figure

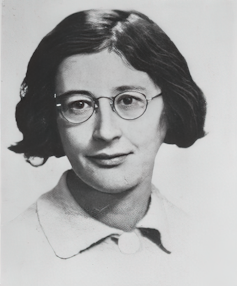

Weil is one of the 20th century’s most remarkable and paradoxical figures. She was born in Paris in 1909 into relative affluence, but she came to identify intensely and actively, with the poor and vulnerable. (This led her to take leave from teaching, at one point, to labour within the harsh factories of Paris.)

A first-rate scholar of philosophical thought (topping the entrance exam for the prestigious École normale supérieure), she set aside an academic career to direct her prodigious energies toward social activism.

A committed pacifist, she spent time on the front lines of the Spanish Civil War.

A secular Jew by birth, she nonetheless came to develop an intense Christian faith and practical devotion.

Weil died in 1943 at the age of just 34 in a sanatorium in Ashford, Kent, in circumstances that are still debated. She had contracted tuberculosis, but she had also been restricting her diet in solidarity with the suffering people of occupied France. So ended a life of almost unrelenting intensity and devotion.

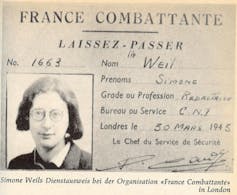

The Need for Roots was written under these conditions of great physical duress. Weil had been requested by the “Free French” resistance movement in London to write a report on the possibilities of bringing about the regeneration of France after the end of the second world war.

The result was nothing less than a tour de force of ethics and political philosophy, set in a lucid historical context, with an unrelenting eye on practical imperatives for rebuilding the French nation.

The needs of the soul

Weil’s book is marked by both socially conservative and economically progressive themes. In some senses, her thought anticipates so-called “postliberalist” positions in our own time, which reject both individualism and globalist economics.

She believes in strong local communities, condemns economic exploitation of the poor, and is deeply suspicious of the motives of the modern, centralised, bureaucratic state.

A deep traditionalism runs through the work, guided by a strong, virtue-based, spiritual understanding of the good life and the common good, which places powerful obligations on all people. Yet she is unrelentingly focused on compassion for society’s most vulnerable: both functionally enslaved urban factory workers and impoverished and marginalised rural peasantry.

The book begins not so much with a focus on rootedness, but with a short, extraordinarily dense manifesto highlighting a series of other fundamental “needs of the human soul”.

Weil gives priority to obligations over rights. She insists on the importance of personal responsibility as well as liberty. She affirms freedom of opinion, but she is no libertarian in this regard (truth trumps any right to propagandise).

She cherishes social equality, emphasises the value and honour of all professions, but also defends the legitimacy of hierarchy and punishment. There is a recognition of the need for order, property (private and collective) and security, alongside the importance of risk for the development of ambition and courage.

Work is an essential need of the soul for Weil (she speaks at one point of the “spirituality of work”). But not work that crushes the spirit with tedium or violence.

Read more: Friday essay: what do the 5 great religions say about the existence of the soul?

Urban and rural forms of uprootedness

Weil then turns to what she considers to be the chief challenge of the times: addressing the uprootedness of peoples in both urban and rural France, as well as the uprootedness of the French nation as such. Her observations and diagnoses here are often as acute as her prescriptions for addressing them.

The common theme throughout these sections is of a directionless society in need of a rejuvenated sense of active community life in which people have a sense of purpose and an opportunity to contribute. The parallels with our own time are striking.

In her analysis, urban workers face the twin perils of either unemployment or exploitation in workplaces that afford little or no opportunity for intrinsic reward from their labours. Meanwhile, an impoverished educational system pays little regard to the value of learning for its own sake, failing to provide the young with any serious historical context in which to orientate a larger sense of belonging and destiny.

This amounts to a “dangerous malady”. Workers can either fall into a “spiritual lethargy” or lash out in often violent ways against a system that traps them and offers little respect.

The plight of French rural workers is similarly perilous. She writes of the unhealthy rift between rural peasantry and urban workers, the depopulation of the countryside and the “ennui of French Provincial towns”; poverty, poor educational opportunities, and narrow cultural horizons.

Weil’s diagnosis bears comparison with contemporary western challenges: frustrated aspirations, precarious employment arrangements, social anxiety, economic fragility, the urban-rural divide, and educational systems in a crisis of purpose.

Her focus on the exploitative effects of mid-20th century workplace technologies and new patterns of work bring to mind shifts towards the gig-economy and other modes of employment today that often restrict workplace and labour union solidarity.

Read more: How to stop workers being exploited in the gig economy

In a similar way, Weil’s highlighting of the potential for popular indignation against the perceived culprits in her time (politicians, industrialists and those who collaborate in their schemes) prefigures contemporary outrage against so-called cultural and economic “elites” who have little regard for ordinary people, and who champion globalist values over local identities.

As British author David Goodhart has argued, the resulting “us-and-them” atmosphere further corrodes social cohesion while providing the basis for violent protest.

Weil’s warning about social rootlessness is no less pertinent today:

A tree whose roots are almost entirely eaten away falls at the first blow.

The idolatrous nation state

Though Weil was writing during the emergency of the second world war, in her view the origins of the problem of rootlessness go well back in history.

The rise and supremacy of the “state” in modern times, she suggests, has been a disaster for other more organic forms of sociality. This abstract entity (“the state”) has conquered and subsumed all other modes of social connection and loyalty: extended family, village, district, province, or region.

It uses its citizens for its own ends, including as cannon fodder in wars of conquest, while simultaneously demanding absolute loyalty through patriotism.

Here she sees the malign influence of Roman imperialism behind the growth of the powerful French state, which developed in the 17th century. Not only were provinces conquered and uprooted to create the modern French state, but as an imperial power it, in turn, uprooted and assimilated other territories, thus spreading the contagion. The wartime occupation of France by the more recently developed German state was a manifestation of the same phenomenon.

It is not that Weil is opposed to national patriotism as such (understood as a love of one’s own people). Her virulent opposition is rather to the state as an idol demanding absolute obedience.

Weil’s insights into the connection between the power of the modern state and the phenomenon of autocratic rule are especially poignant:

The State is a cold concern which cannot inspire love, but itself kills, suppresses everything that might be loved; so one is forced to love it, because there is nothing else […] Here lies perhaps the true cause of that phenomenon of the leader […] who is the personal magnet for all loyalties. Being compelled to embrace the cold, metallic surface of the State has made people, by contrast, hunger for something to love which is made of flesh and blood.

Such an explanation of the prevalence of authoritarian figures in the 1930s bears fascinating comparison to our own time. It is almost uncanny in anticipating the power of mass media in “manufacturing stars out of any sort of human material”, and giving “any sort of person the opportunity of presenting himself for the adoration of the masses.”

If Weil perhaps had in mind Leni Riefenstahl’s portrayal of Hitler, contemporary examples of strongman leaders (such as Trump, Bolsonaro, Putin) using media to elicit popular adoration that can be weaponised against civil institutions and “enemies of the people” come easily to mind.

In this and so many other respects, Weil’s analysis of the perils of rootlessness retains its bite in our own context.

For one whose work was so little read during her lifetime, her influence (which grew strongly in the decade after her death) continues to be profound, in social and political thought, but also in religious studies.

Weil’s wise and passionate writings reward frequent re-reading and reflection.

Richard Colledge does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.