Although I’m wary of declaring any literary work to be the greatest ever, Shakespeare’s Hamlet would be a frontrunner. It’s often proclaimed to be or voted Shakespeare’s best play (Google it). It has countless film adaptations, is widely referenced, and even gets a homage of sorts in The Simpsons.

Hamlet deserves such accolades because it offers the deepest of insights into the human condition; although this insight can be a little tricky to explain.

Let’s consider some of Shakespeare’s other popular, serious plays. Romeo and Juliet is a tale of forbidden love – the cliché drops effortlessly. Othello is about the horrors of jealousy. And Macbeth, with its Tarantino-grade account of regicide and its grim consequences, explores the dark side of ambition. So what about Hamlet?

Well … ah … It’s about when someone does something bad, and you’re pretty sure what they did wasn’t right, and you ought to do something about it, but you can’t find it within yourself to do this something, and your uncertainty and inaction cause you even more distress, but events roll on – as they always do – and everything ends up worse than if you’d done something in the first place. Maybe.

I’m being silly, but it’s my way of coping. For while I’m familiar with the woes associated with love, jealousy and ambition, my greatest grief is that time and again I did not act when the situation called for it. I was a coward. I’m certain that I’m far from alone in assessing my life this way. And this is why Hamlet, which depicts this state of inaction, is the Everest of literature.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Homer's Iliad

An overview of the play

Hamlet, the prince of Denmark, is a modern character. He attends the University of Wittenberg and is an intellectual. His father, the recently deceased king, also called Hamlet, was, in contrast to his son, a warrior.

In the play’s first scene, the ghost of old king Hamlet silently appears to Horatio, Hamlet’s friend. Upon seeing him, Horatio recalls the time when “in an angry parle [a battle], / He [the old king] smote the sledded Polacks on the ice.” This counterpoint to Hamlet’s famed inaction, like the ghost of the king itself, haunts the play.

We soon learn that the old king has only been dead two months and that Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, has hastily married the new king, Hamlet’s uncle Claudius.

The ghost of Hamlet’s father returns, this time telling his son he was murdered – poisoned – by Claudius (it was “murder most foul”) and urging Hamlet to avenge his death.

The scene finishes with young Hamlet revealing reluctance:

The time is out of joint: – O cursed spite, / That ever I was born to set it right!

But the ever more troubled prince is uncertain whether the ghost even spoke the truth. He gains proof when he asks a troupe of actors to reenact the poisoning before Claudius and Claudius reacts strongly.

Now Hamlet really must avenge his father. The opportunity arises when, on his way to meet his mother, he comes upon Claudius praying. But Hamlet is beset by doubts and cannot kill Claudius.

Hamlet goes on to confront his mother about her hasty marriage. While arguing with her, he stabs Polonius (the father of Ophelia, the woman he has been courting), who had been planted behind a curtain to spy on him.

Polonius’s son Laertes wants to avenge his father. He, unlike Hamlet, is willing to act.

Claudius, who now also wants Hamlet dead, arranges for Laertes to fight a duel with Hamlet with a poisoned rapier. They fight. Hamlet is cut by the rapier, and then Laertes is too. Meanwhile Hamlet’s mother accidentally consumes a poisoned drink intended for her son and dies.

Hamlet learns the truth of what has happened. He stabs Claudius, making him drink the poison too. Claudius dies, then Laertes dies, then finally, Hamlet dies. (South Park efficiently represents the final scene).

To be or not to be – or maybe not

I had expected to illustrate Hamlet’s struggle to act with an analysis of the most famous speech in all of Shakespeare: ‘To be, or not to be’ (Act III Scene I). It begins with these oft-quoted lines:

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

But now I’m not so sure it’s a good idea. “To be, or not to be” is ambiguous. Also, Hamlet probably knows he is being watched by the king or others while he is speaking, and thus is not really speaking his mind.

Arguably, Hamlet’s definitive speech in the play comes just before this one, at the end of Act II. In this red-blooded soliloquy, he berates himself for his inaction, asking, “am I a coward?” and reflects that he lacks the gall, “To make oppression bitter”.

He says, ‘I should have fatted all the region kites / With this slave’s offal’; i.e. murdered Claudius and fed his guts to the carrion eaters.

He also mocks his proclivity to seek solace in words:

Why, what an ass am I! Ay, sure, this is most brave;

That I, the son of a dear father murder’d,

Prompted to my revenge by heaven and hell,

Must, like a whore, unpack my heart with my words…

The refusal of the call to adventure

Shakespeare’s play is notable because it tells of one who, to draw on Joseph Campbell’s enduring concept of the “hero’s journey”, refuses “the call to adventure”.

So many of the stories we consume involve some sort of heroic quest where a reluctant hero accepts this call. Observe Frodo in Lord of the Rings or Luke Skywalker’s ambivalence around the call in Star Wars. Both heroes end up defeating evil. And while they are changed by the experience (not entirely for the better), one senses that refusing the call would have led to worse outcomes.

Hamlet’s inaction – his refusal of the call – directly or indirectly causes eight deaths, including his own. If he had acted, then probably only Claudius would have died.

The moral of the story is that there is risk in action, but the greater risk lies in inaction. In short, action, in bad situations, is the lesser of two evils.

But maybe this isn’t the moral. Maybe the play is not exhorting the audience to act, but asking a deeper question. Namely, what does it mean for us to cross the threshold that separates reason from power? That is, what does it mean for us to abandon reason and strike back at the monster?

Reason appeals to principles. It appeals to the capacity for reason in others. It doesn’t take the law into its own hands. But what if it is sometimes reasonable to abandon reason and strike at power with power? Can reason survive such a decision?

The endless appeal of Hamlet

Hamlet is not only successful because Hamlet himself embodies our own struggles. Hamlet is also staggeringly quotable – the quip is that there are too many quotations in it.

The play’s appeal also lies in the depth of the secondary characters, such as Ophelia, Polonius and the inseparable Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (Hamlet’s friends from university).

And the play is seductively enigmatic. We are unsure whether Hamlet’s mother was in on the murder of the old king, whether Polonius is indeed a fool, whether Hamlet loses his mind, and so on. Where there are mysteries, there are detectives.

Hamlet turns up everywhere in Western culture – not just in The Simpsons and South Park.

Given all the trouble Hamlet has with his father and mother, it’s not surprising that Freud saw something Oedipal in the whole business.

Ophelia, who suffers the double tragedy of her own demise and being less discussed than Hamlet despite having a compelling struggle and brilliant lines (“we know what we are, but / know not what we may be”), is referenced in Eliot’s The Waste Land. Her words, “Good night, ladies; good night, sweet ladies; good night, good night” provide a foreboding conclusion to the ghastly pub scene in Part II of Eliot’s poem.

And for the Star Wars fans (one Star Wars reference is never enough), Chewbacca has his own “Alas, poor Yorick” moment when he is reassembling C3P0 in Empire Strikes Back (Yorick was a jester who entertained Hamlet when Hamlet was a boy).

Compare this with Kenneth Branagh’s version.

Memento mori

All this said, and with Yorick in mind, what stands out most for me in Hamlet is the dark and beautiful graveyard scene at the beginning of Act V.

Polonius is dead. Ophelia, whom Hamlet probably loved, is dead. The bloody final sequence is nigh.

And the play pauses.

Two gravediggers have a wry debate about whether or not Ophelia committed suicide as they are digging her grave. It’s a moment of blackest comedy.

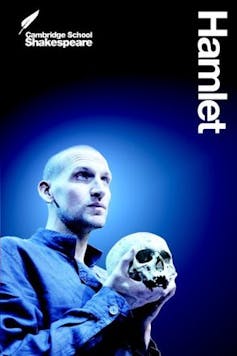

The gravediggers unearth Yorick’s skull. After Hamlet’s “Alas, poor Yorick! – I knew him”, Hamlet reflects that the most famous people, such as Alexander the Great and the Roman emperor Caesar, ended up no different to Yorick.

Imperious Caesar, dead and turned to clay

Might stop a hole to keep the wind away.

Oh, that that earth, which kept the world in awe,

Should patch a wall to expel the winter’s flaw!

Despite exploring the most serious aspects of the human condition, Shakespeare, with this memento mori, seems to be reminding us that existence has something of the cosmic joke about it. This is reminiscent of the ending of Life of Brian. Roll the credits.

Dr Jamie Q Roberts does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.