Tuesday Greenidge is a multimedia artist based in North Kensington, London. When Grenfell tower caught alight on the night of June 14, 2017, her daughter was in the lift. She managed to escape. She came to her mother’s home to tell her Grenfell was on fire.

In the five years since, Greenidge has been working on a quilt in memory of the 72 people who lost their lives that night. As she explained in a recent BBC interview:

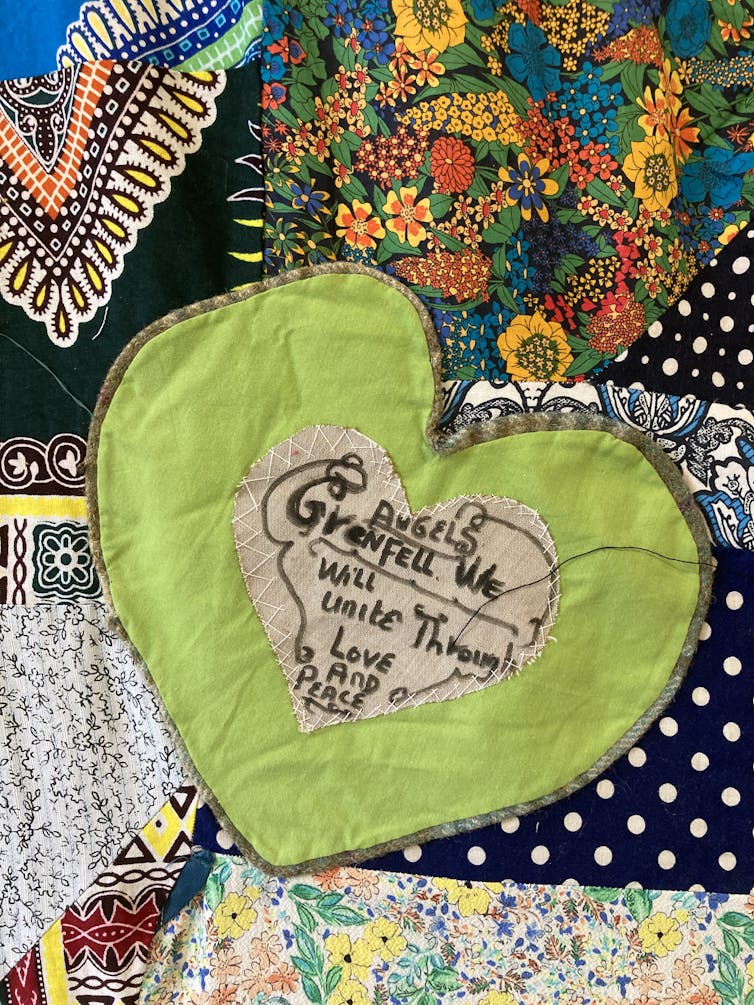

I wanted to salvage all the messages of love and condolence and defiance and prayers that grew organically around the walls and the fences around our community.

The Grenfell memorial quilt is inspired both by the world’s largest quilt, the Portuguese manta da cultura and the fabled Aids memorial quilt (which, in its first, 1987 iteration, featured the names of 1,920 people who had died from the virus). Greenidge’s idea is that it will ultimately be as wide and as long as Grenfell tower itself.

Artistically, this project is a monumental undertaking. Socially, it operates as a vital connector, a way for people to come together, to remember, to talk – and hopefully, to heal.

I have been designing and making quilts, individually and collaboratively, for over 25 years. As a textile academic, practitioner and researcher, I have found that quilt-making gives people the means to engage with the key issues of our time, be it social injustice, migration, identity, sustainability or health and wellbeing.

How a quilt is about preserving memory and bearing witness

Quilt-making is an art form with a long and global history, which stretches back to medieval times. Generally comprised of three layers of fabric, the top often pieced together in a patchwork, quilts are a kind of repository for memories.

Most commonly used as bedclothes, quilts quite literally provide comfort and protection. But this capacity extends beyond their practical uses, too. I have found that they are an important non-verbal means of communication. Greenidge has said as much. Speaking of the night of the fire, she has said:

It’s only years after that you can find the actual words to kind of describe it. That’s why I make art, to find other ways to express how I felt.

She began stitching small patches at home, then started running a weekly sewing bee in various locations. Every Tuesday the group now meets in the North Kensington library. Anyone is welcome to join in.

Talking about making the quilt communally, she has said that it feels wonderful, “like the power of people when they come together”. She says she dreams of it being taken up by BBC One’s Great British Sewing Bee and a nationwide army of quilters.

This power starts with the basic component of which quilts are made. Cloth is a potent physical reminder of people; the smell, the texture or simply the feel of a garment can help us to recall a presence.

Because it is made from donations, the Grenfell quilt has its history inscribed upon its surface. Slowly, names of the people who died in the fire are being stitched on to the quilt, along with green crocheted hearts, stuffed animal toys and embroidered versions of the spontaneous messages and drawings people left on the walls and fences around the tower. These fabric mementos act as sensory affirmations that these people are not forgotten.

The quilt as collective action

The Aids memorial quilt was a visceral and emotional response to social injustice and loss connected to the Aids crisis. As Gregg Stull, one of the academics involved in exhibiting it early on, wrote in 2001, “The eloquence of the quilt will stand as witness to a terrible time and a devastating loss of lives.” Similarly, the Grenfell quilt serves as a collaborative tool in a shared process of healing.

The names sewn into the quilt are also reminiscent of signature quilts. Featuring a mass of needlework autographs, they began in the US and gained popularity in the UK in the late 19th century.

While not as plentiful or varied as their American counterparts, I have unearthed a substantial number of British signature quilts in museums from the Quilters Guild in York to the Moravian community archive in Greater Manchester and several private collections. Made as fundraisers during the two world wars, these quilts are stitched commemorations of people and place.

In 2011, I worked with a refugee and asylum seekers organisation in East Manchester, called Rainbow Haven, to create a contemporary signature quilt. Much like the Grenfell quilt, it shines a light on an important but underrepresented group.

The Grenfell quilt, with its focus on the overlooked serves as a soft, tactile, portable counterpoint to the ubiquitous hard memorials, fixedly located in parks and city centres. When it is finished, this pieced cloth will be 67m long, as long as the tower is tall. Already, it stands as a sobering reminder of the enormity of this community’s loss.

The Grenfell memorial quilt will be on show at the Festival of Quilts, August 18-21, 2022, at the NEC in Birmingham. To find out more, follow on Instagram and Twitter.

Lynn Setterington does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.