A black screen and fragments of birdsong give way to blue sky, and the watery light of a low sun over fields, trees and the snaking streets of suburban sprawl. The camera moves – reeling towards a white arch reaching into the sky. Wembley Stadium comes into focus as London’s skyline swims at the horizon; a polluted mirage. Occasional sirens. The screech of trains. Then, tower blocks start to punctuate the landscape. Four are concrete grey, but the one in the centre – the one the camera keeps moving closer and closer to – is black. Charred. A burnt-out husk that steadily fills the screen, as the city soundscape rises to a fever pitch, before abruptly dropping into silence. The remains of Grenfell Tower confront you: stark, shattered and excruciating.

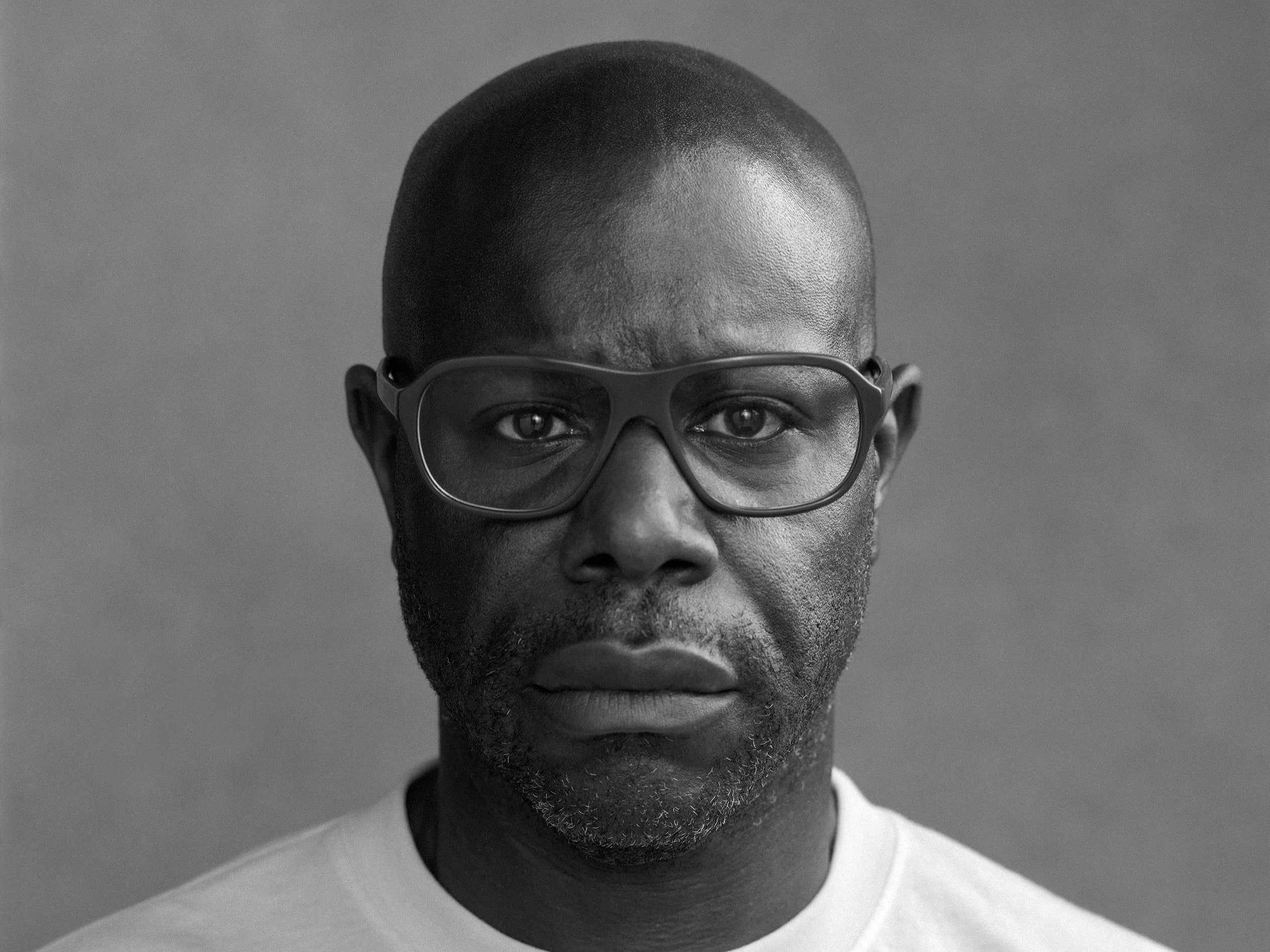

This is Grenfell – one unedited shot, 24 minutes and 2 seconds long – filmed by the artist Steve McQueen and showing at London’s Serpentine South Gallery in Kensington Gardens, just outside the boundary line of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, where Grenfell Tower’s fire-ravaged reproach still stands to this day. “I feared once the tower was covered up it would only be a matter of time before it faded from the public’s memory,” McQueen writes of his decision to film the tower, six months after the devastating fire that claimed the lives of 72 Grenfell residents, leaving hundreds more injured and bereaved. “In fact, I imagine there were people who were counting on that being the case.”

In December 2017, McQueen strapped himself into a helicopter and flew over London’s northern expanse, towards the gutted tower. Shortly afterwards, it was wrapped in layers of white plastic, like a colossal shroud. Again and again, McQueen’s camera circles Grenfell – spinning around the face where orange scorch marks in the building’s murderous cladding make it look still ablaze, to the scaffolded side all in shadow, like a satellite orbiting the moon. It is hypnotising in its horror. As the film pulls in close, piles of pink plastic bags stuffed with debris can be glimpsed through what were once windows. Later, a few forensic specialists can be seen, decked in PPE, before the camera’s rotation conceals them behind bubbled cladding panels.

Some will undoubtedly question the ethics of a film that peers so closely and intently at the razed remains of what were people’s homes – the places where so many lived, and so many died. It is certainly true that, while gripped by Grenfell’s awful sight and silence, the names of the dead and the testimony of survivors also seem to circle. Rania Ibrahim, who lived on the 23rd floor with her husband and two daughters; Fethia, aged four, and three-year-old Hania, who both died in the blaze along with their mother. Marjorie Vital and her 50-year-old son Ernie, whose bodies were found together in their bathroom on the 16th floor. Each loop of the block: other lives on other floors; other deaths. But what remains achingly clear for the film’s full length is that the Grenfell Tower McQueen’s camera circles is not only a monument of tragic loss and a traumatised community, it is a crime scene. “It was not an accident,” Paul Gilroy writes in Never Again Grenfell, an essay that accompanies Serpentine’s gallery text. Repeated warnings went ignored. Dangers were concealed or minimised in the service of profit.

In January, Michael Gove admitted that “faulty and ambiguous” government guidance was partly responsible. “The government did not think hard enough, or police effectively enough, the whole system of building safety,” he told The Sunday Times. In a further interview for Sky News, Gove, who is currently secretary of state for levelling up, housing and communities, said lax regulation allowed cladding firms to “put people in danger in order to make a profit”. At the time of his comments, only 7 per cent of UK homes covered with fire-risk cladding – which house an estimated 700,000 people – had been fixed.

McQueen’s project, which has involved extensive consultation with the bereaved, survivors and neighbours, comes as the Grenfell community waits for the findings of the second and final phase of the government inquiry that was launched after the fire. These are due to be reported later this year, four years after the publication of the phase one report. As it stands, the recommendations of that report are yet to be implemented, and the ongoing criminal investigation is yet to bring anyone to trial. It has been revealed, however, that a major shareholder in Arconic, the company that made Grenfell Tower’s combustible cladding, donated nearly £25,000 to the Conservative Party.

“Who can be killed without any consequences?” Gilroy writes. That, he indicates, is the “basic question... pending in the memory of Grenfell Tower just as it was in the long, multi-layered struggle over the 97 people who died on the terraces at Hillsborough”. On one of Grenfell’s awful loops, a car drives past below; on another a train cuts along from Latimer Road station. To say it is jarring to see life continue around the tower is an understatement. But it is of course what happened. The world carried on, much the same as before. “Whose lives matter,” Gilroy asks, “which deaths will be mourned? How can these acts of gratuitous killing be marked and remembered?” How can art respond to such a tragedy – one that could and should never have happened if warnings were heeded; one that stole lives needlessly, in the reckless and selfish enterprise of greed – and how can the community grieve when Grenfell’s slow violence still seeps out, and when justice is kept deliberately out of reach? No justice, no peace.

Five years on, monthly silent marches, the work of survivors, allies, activists and agitators, and the community’s relentless campaign for justice have stopped Grenfell from being forgotten. When the film comes to its close, a rush of noise suddenly surges in. It feels like screaming.

‘Grenfell’ is screening at Serpentine South, Kensington Gardens, London, from 7 April until 10 May