First released in New York on December 4 1924, Erich von Stroheim’s intense, monumental Greed remains more famous for what didn’t end up on screen than what did.

Based on Frank Norris’ 1899 novel McTeague, Greed is a psychologically intense story of the corrupting influence of capital.

Miner John McTeague (Gibson Gowland) journeys from northwestern California to become an (unregistered) dentist in San Francisco. There he courts and marries a local woman, Trina (ZaSu Pitts).

Drawing on a notorious murder of the 1890s, Greed dramatises his downward spiral, ending in “escape” to the forbidding vastness and isolation of Death Valley.

Greed was a financial failure on its initial release and received a mixed critical reception. But it quickly went on to be regarded as one of the great silent films and a key influence on many subsequent filmmakers and film archivists.

Self-made legend

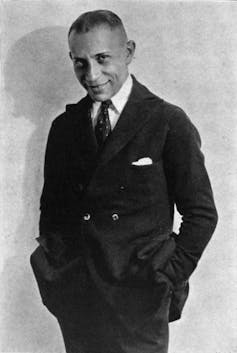

Stroheim was always a larger-than-life figure who actively embellished his own legend.

Arriving in the United States in his early 20s as a poor immigrant from a Jewish background, he claimed an aristocratic heritage – hence the “von” – and became a star in Hollywood. During World War I, he played an array of sadistic Prussian officers on screen and was touted as the “Man You Love to Hate”.

After working with director D. W. Griffith on films like The Birth of a Nation (1915), Stroheim began his directorial career in 1918. He quickly became notorious for his attention to detail, budgetary extravagance and fondness for excess and perversity.

Although stories about him insisting that soldiers in his 18th or 19th century set dramas must wear period appropriate underwear are almost definitely apocryphal, they pinpoint the extraordinary combination of the realistic and the baroque that marks his work.

After making a series of increasingly ambitious and often financially successful films in the late 1910s and early 1920s, in which he also often starred, Stroheim was contracted by Goldwyn Pictures to make a series of films.

The first of these was Greed.

A novel cinema

Stroheim was given considerable creative freedom on this project as well as some latitude in terms of its escalating budget.

The film’s often gritty and close to contemporary setting, as well as its American subject matter, were something of a departure for Stroheim. But the director plainly found a theme to match his escalating ambition in Norris’ downbeat novel and set about translating it to the screen on an epic and intimate scale.

Although many accounts suggest Stroheim aimed to adapt every full stop and comma of the novel to the screen, the reality is much more nuanced, with many additions also made to the material.

This mammoth production was shot over 198 days in 1923 with approximately 85 hours of footage captured. This was subsequently whittled down to around nine hours, a version shown to a select audience including other filmmakers and studio executives.

This version’s emphasis on expanding out particular incidents, psychologies and interrelationships was supposedly remarkable – even revolutionary. But this was never a version that was going to be commercially released.

Over the next few months various other cuts of the film were made, initially under Stroheim’s supervision, before a significantly shortened and bowdlerised version at just over two hours was released.

Many of the subplots and various characters were removed, diminishing its scope and downplaying German-American film director and producer Ernst Lubitsch’s claim Stroheim was “the only true novelist in films”.

This may seem like a backhanded compliment, but Lubitsch’s claim highlighted the thick detail and thematic ambition of Stroheim’s cinema as well as its profound connection to the work of realist novelists like Norris and Émile Zola.

Lasting legacy

After 100 years, why is Greed still an important film and influence?

Filmmakers such as Christopher Nolan, Jean Renoir, Josef von Sternberg and Sergei Eisenstein have cited it as inspiration.

It’s hard to imagine it wasn’t an important model for Paul Thomas Anderson’s similarly themed There Will Be Blood (2007) and a playful reference for Christoph Waltz’s dentist-turned-bounty-hunter in Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained (2012).

It has also long been a catchword for a certain kind of realism or naturalism in cinema.

Stroheim shot most of the film on location including a hellish two months at the height of summer in Death Valley for the film’s brilliant but brutal final stanza.

Although many of the novel’s San Francisco settings were destroyed in the 1906 earthquake, Stroheim still insisted on locating the places where the novel was set and using many of them.

The film remains remarkable for its sense of detail, its psychological intensity and its placement of its characters within actual environments.

But the true lasting legacy of Greed is more closely related to the extreme models of filmmaking it promoted. The “full” version of the film is one of the great “holy grails” for film archivists, even though the excised footage was allegedly destroyed not long after production. It is one of the films first mentioned whenever a filmmaker’s vision or excesses are brought into question.

It is the chief example, along with Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), of the great lost, once complete film but also of the indignities suffered by uncompromising artists in Hollywood.

Stroheim would go on to make a series of other films in the 1920s, some equally vexed, and then forge a varied career as a striking character actor. As an actor, he is best remembered for his dignified appearance in Renoir’s La grande illusion (1937) and the very close-to-the-bone Max von Mayerling in Sunset Blvd. (1950).

But Greed, and all it represents, remains his greatest legacy.

Adrian Danks does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.png?w=600)