Fanned by strong winds and record temperatures, wildfires on the Greek island of Rhodes recently spread from the hilly interior to the densely populated coastline with astonishing speed, leaving authorities with the daunting task of evacuating thousands of residents and holidaymakers from harm’s way.

The role of climate change in heightening the risk of wildfires cannot be ignored. The world is, on average, 1.2°C warmer than in the pre-industrial climate, and this extra heat is bringing more frequent heatwaves and droughts. These weather conditions make the environment more fire-prone, and their increasing frequency has exposed already fire-susceptible regions such as the Mediterranean to greater risk of disaster.

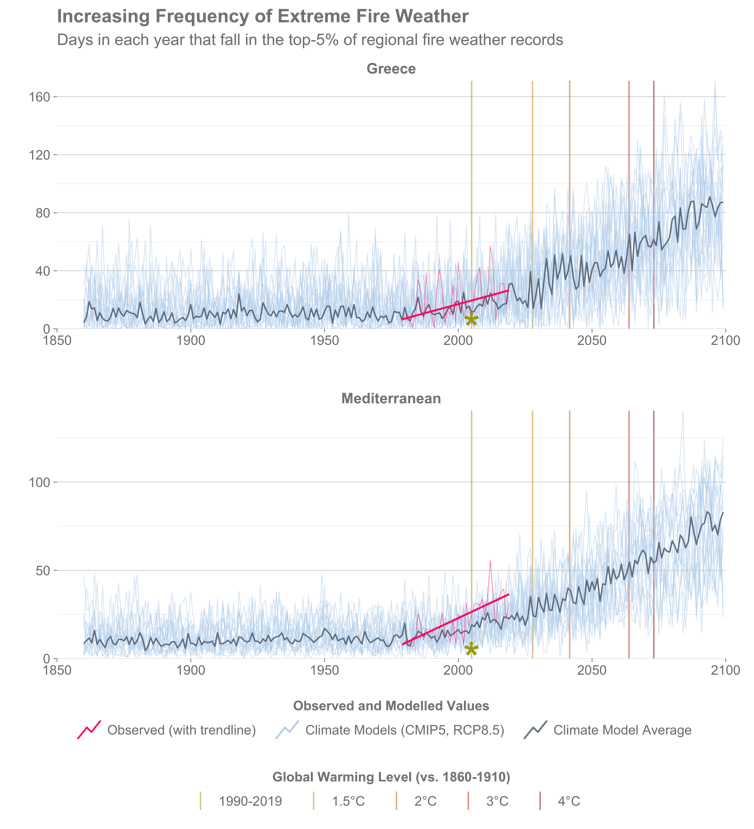

Scientists use a fire weather index to estimate how flammable vegetation becomes under a set of weather conditions including temperature, humidity, wind speed and how recently rain fell. In the Mediterranean, the frequency of extreme values on this index has increased faster than virtually anywhere else on Earth since the late 20th century. As a result, the Mediterranean now faces 29 additional days of extreme fire weather a year.

Greece’s recent bout of extreme fire weather emerged from a heatwave that would have been at least 50 times less likely in the pre-industrial climate. Days with extreme fire weather are set to increase through to 2100 if emissions are not reduced.

Due to changes in the global climate, the UN Environment Programme predicts an increase in extreme wildfires of up to 14% by 2030 and 50% by 2100. Even at 1.5°C of warming (the threshold nations pledged to halt temperature rise to as part of the 2015 Paris Agreement), a 40% greater area is expected to burn in the Mediterranean.

Breaking down the causes of wildfires

When attributing the cause of a wildfire, it is important to distinguish between the factors that cause a fire to ignite and those that cause vegetation to become so dry that they are primed to burn. Climate change alone cannot ignite a fire – a spark from an ignition source or lightning is necessary.

Arsonists were blamed for starting at least some of the fires in Greece, although arson is actually a minor cause of wildfires in the country. Of the past Greek wildfires with a verified ignition cause, only 23% were caused by arson. Most arose from fires on farmland initially started to burn crop waste or encourage new growth of pasture grasses, or from fires on scrubland and grassland that were lit to manage unwanted vegetation.

With climate change providing more of the conditions that support fire, fresh opportunities are arising for people to start fires, whether on purpose or by accident.

The frequency of extreme fire weather will accelerate if global warming exceeds 2°C, but the world can still avoid the most severe outcomes by rapidly reducing emissions of greenhouse gases. It is not too late to stop burning the fossil fuels that are driving climate change and extreme weather.

The worst can still be avoided

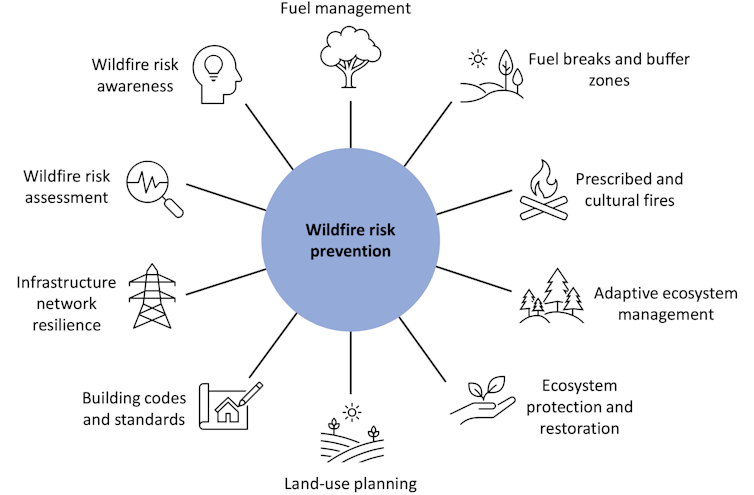

Regions like the Mediterranean have naturally fire-prone landscapes, and it is unrealistic to expect people to exclude fire from their lives completely. Society must learn to adapt and live with fire while increasing preparations for more extreme fires in the future.

Wildfire budgets have historically prioritised fighting active fires. For example, in Greece, 92% of the national budget for forest fires was devoted to suppressing fires during the 2010s, with only 8% devoted to preventing them in the first place. As well as investing in firefighting teams and equipment, countries should develop better early-warning systems, evacuation plans, fire-resistant buildings, and computer models of fire behaviour. Programmes that make communities more aware of their role in fire safety, including stopping arson and accidental ignitions, are also critical.

In many parts of the Mediterranean, decades of rural land being abandoned have caused vegetation to grow more densely than in the past. This denser vegetation can mean more fuel for wildfires, promoting more intense burning. One option to keep this fuel in check is to use controlled burns during safe weather windows.

The wildfires in Greece are a stark reminder of the threat posed by climate change, and the costliness of missing international targets to reduce emissions. Decisive action to curb emissions, manage fuels on the landscape, and prepare communities can still lower the risks that fires will pose in future.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Matthew William Jones receives funding from the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NE/V01417X/1).

Chantelle Burton receives funding from the Met Office Climate Science for Service Partnership Brazil (CSSP Brazil).

Douglas Kelley received funding from the UK Natural Environment Research Council (projects LTSM2 TerraFIRMA, NC-international programme, NE/X006247/1).

Stefan H Doerr receives funding from the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NE/T003553/1; NE/R011125/; NE/X005143/1) and the European Commission (H2020 FirEUrisk project no. 101003890).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.