Greenhouse gas emissions in Wellington, Wairarapa and the Kāpiti Coast will halve by 2030 under the regional council's new target, which goes further and faster than central government, Marc Daalder reports

Climate change will be embedded into almost all relevant decision-making at Greater Wellington Regional Council, as part of a sweeping set of policy changes expected to be agreed to on Thursday.

An order paper released on Monday ahead of the regional council's meeting later this week shows it will commit to a stringent emissions target to halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2030.

Sub-targets would see a 35 percent reduction in emissions from land transport, a 60 percent reduction in emissions from public transport and a 40 percent increase in walking, cycling and public transport use by the end of the decade.

Come 2050, the region would reach net-zero emissions.

The new climate objectives and policies come as part of an update to the Regional Policy Statement to align with new requirements around urban development and freshwater management.

"We have gone quite early in terms of updating our Regional Policy Statement. We have to do it for the National Policy Statement on urban development by the end of this year and I think for the freshwater rules by the end of next year, and so we've decided to just do it all in one pop," Thomas Nash, the chair of the regional council's climate change committee, told Newsroom.

"While we were there, we thought, hey let's put in some climate stuff as well. I was very encouraged that we have put in this emissions reduction target and not only have we put in a target but we've made it one that actually aligns with the Paris Agreement, rather than a weaker one."

The updated Regional Policy Statement will make Greater Wellington the country's first regional council to set a binding emissions target. And the commitment to halve emissions from 2018 levels by the end of the decade is more ambitious than the Government's national emissions budgets, which would reduce emissions by just 30 percent.

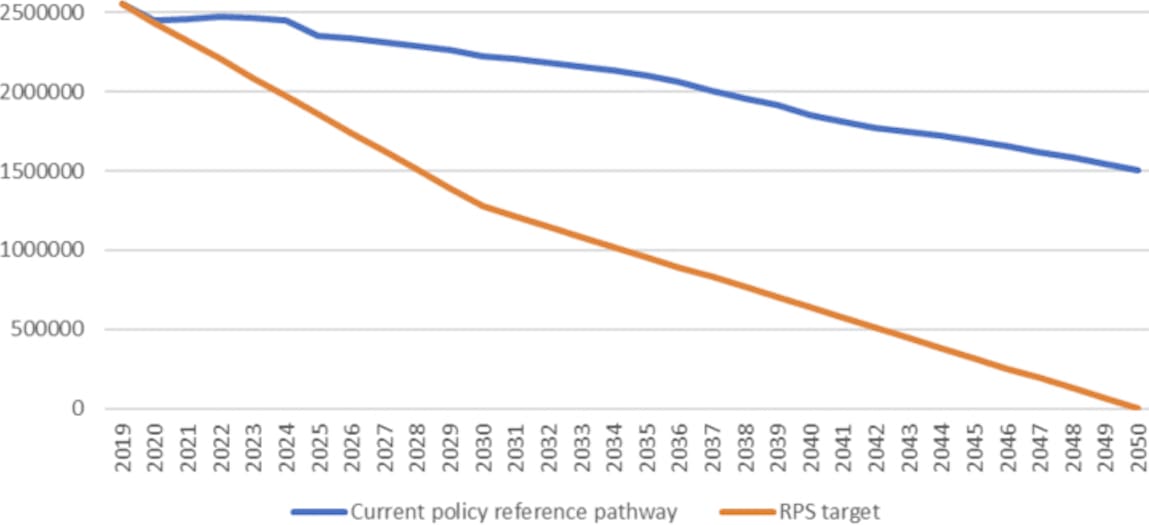

If the targets are met, 5.6 million tonnes of emissions in Wellington, Wairarapa and the Kāpiti Coast would be avoided by 2030, compared to emissions expected under current policy settings. Those cumulative savings would rise to 30.7 million tonnes by the middle of the century.

Regional net emissions pathways (all gases, tCO2-e)

The council used shadow emissions prices from the Treasury to estimate the expected economic impact of the emissions cuts given future carbon price pathways, which showed the regional economy would save $5.87 billion by 2050. If the human and social cost of greenhouse gas emissions is considered, the savings rise to $10.75 billion.

To accomplish the targets, the new Regional Policy Statement will include a range of new policies and new climate components added to existing ones.

These include a requirement for district and regional plans to maximise mode shift away from private vehicles in all new and altered transport infrastructure. By July 2025, district councils will require consent applicants to provide "travel demand management plans" which "minimise reliance on private vehicles and maximise use of public transport and active modes for all new subdivision, use and development" over a certain threshold.

"We're putting the marker down and we're doing it because we know that we have to meet those climate targets and confront the climate reality that we face." – Thomas Nash, Greater Wellington Regional Council

Changes to urban design rules within the new climate section of the Regional Policy Statement and the urban development section will encourage low-emissions infrastructure alongside new housing.

"In Wellington, one of the biggest drivers for emissions reduction is going to be urban form. There's some stuff in there around urban intensification where we're making it more difficult for car-dependent suburbs to be developed," Nash said. "We're essentially wanting to bake in rules into all of the planning documents that will be coming out from district councils to say that people have to have more options than just a private motorcar."

Agriculture is also a focus, for the district councils which encompass large rural areas. That sector makes up 34 percent of emissions in the region, second only to transport at 39 percent. To offset residual, hard-to-abate emissions, the climate plan calls for an increase in permanent forest cover in greater Wellington with a focus on native species.

At the regional level, plans dealing with air pollution will also need to consider greenhouse gas emissions, with a specific aim of phasing out domestic and utility-scale coal use by 2030. This is just one of many existing planks of the Regional Policy Statement which will be edited to add climate considerations.

"It's a very conscious decision," Nash said. "You want to almost make it so that every department in every aspect and every policy decision just considers climate as a matter of course. But I think we're not quite there yet that every decision in every public body, in every council, just automatically considers climate as a high priority."

Nash added that one additional purpose of embedding the target in a Regional Policy Statement is to make sure the council is held responsible for achieving it.

He pointed to the recent High Court decision on Auckland's Regional Land Transport Plan, which doesn't set it up to meet emissions targets Auckland Council set in 2020. Lawyers for the council successfully argued the emissions target doesn't oblige the council to "meet or support any specific emissions reduction target" because it was part of a "high-level" document.

While Auckland Council has since released a plan to meet its transport emissions target, Nash said the argument the unitary council used in court wouldn't work for Greater Wellington's target.

"One of the reasons that you're seeing us put our emissions reduction target in the objectives of a Regional Policy Statement is to make it clear that we mean what we say and that this is not something that can be dismissed," he said.

"This is a very firm, clear commitment that we all have to give effect to in all of our planning documents and planning decisions. We're putting the marker down and we're doing it because we know that we have to meet those climate targets and confront the climate reality that we face."