U.S. farmers navigating an unusual combination of risks and surprises in 2022 – including war, pandemic, and soaring inflation – now find themselves staring down the risk factor that’s always been there: weather.

A cold, wet April and May in the Midwest kept many farmers out of their fields for extended periods, resulting in the slowest corn planting pace in nine years. Adverse weather casts even greater uncertainty on acreage, production, and price outlooks for the two biggest U.S. crops and could further unsettle global markets already roiled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, drought in South America, and Covid lockdowns in China. Both winter and spring wheat have experienced weather disruptions as well, with a drought in Kansas affecting the winter crop, and wet weather affecting the spring crop planted in April and May. Recent corn market strength would seem to argue for stepped-up plantings, but prices for nitrogen fertilizer and other key crop inputs have soared as well.

“The Craziest Year”

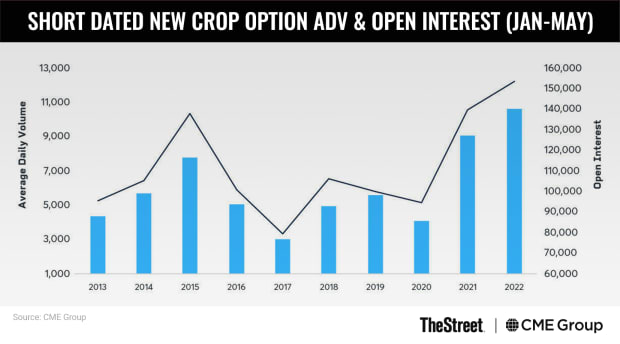

Reese Ivers, who farms near St. Francisville, Ill., said the mix of external factors and risks have made this the most unusual year that he can recall. "This has been the craziest year, with so much going on in the world now,” Ivers said. “Prices are so high, and we’ve seen shortages of key supplies. We’re just in unpredictable times. If we have a drought this summer, watch out.” High grain prices at this time of year may seem like a slam-dunk for farmers, but it’s not that simple. Many are reluctant to forward-sell any expected production this far in advance, considering the risks that drought or another adverse event could rob them of bushels. For farmers, 2022’s confluence of geopolitical turmoil and weather extremes reinforces the importance of nimble hedging and marketing strategies that account for fast-shifting risk considerations. Strong growth in CME Group's short-dated new-crop options, for example, illustrates the agriculture industry’s embrace of hedging tools that can be tailored around expected news (such as USDA reports), as well as the unexpected.

So far in 2022, U.S. farmers' planting decisions have been driven largely by the availability of and costs for crop inputs, such as fertilizer, said Matt Huston, a broker with New Frontier Capital Markets in Chicago. “Corn still pencils out better than soybeans in most areas, but a lack of nitrogen fertilizer has forced some farmers to plant more soybeans or turn to other crops,” Huston said.

The following are a few key risks for U.S. agriculture during the upcoming growing season, including some real use cases for short-dated new-crop options.

USDA’s Acreage Update June 30

The U.S. Department of Agriculture, in its Prospective Plantings report on March 31, projected U.S. soybean plantings at an unexpectedly large 90.96 million acres, up 4.3% from 2021 and a record high. Corn plantings were estimated at 89.49 million acres, down 4.1% from last year and a seven-year low.

The report’s figures were based on farmer surveys conducted earlier that month, weeks before many seeds were in the ground. Since then, corn futures rallied as soggy Midwest weather delayed planting and raised prospects that some farmers may shift acres to soybeans.

With corn and soybean plantings still in flux, the USDA’s annual Acreage report at the end of June looms as a key event that will help set the tone for grain markets for much of summer.

The soybean-corn price ratio, a widely followed gauge of producers' planting inclinations, recently fell to just above 2.0, which would seem to favor more corn acres. But that may not be the case this year. The ratio's recent levels “would normally ‘buy’ a lot of corn acres, but considering input costs and availability, corn's strength versus soybeans is really just keeping the current corn acreage outlook in place,” Huston said.

Ivers, like many Midwest farmers, is planting more soybeans than corn (about 6,000 acres to the former and 5,000 to the latter). Typically, it’s the other way around. But costs for nitrogen, a key fertilizer for corn, have doubled over the past year, prompting some farmers to favor soybeans.

Weather and Yield Risks

Over the winter, drought in South America helped send corn futures above $6.00 and soybean futures above $17.00, historically high levels that may have tempted farmers to hedge at least some of their expected 2022 production. However, locking in prices before the crop is planted carries risks in any year. Drought over the summer could slash yields, for example.

Read more about short-dated new crop options.

Supply-demand dislocations such as what’s occurred in 2022 can cause a disconnect between old-crop and new-crop futures, meaning hedging new-crop production using standard put options that derive value from old-crop futures (July corn and soybean contracts, for example) won't serve as an adequate hedge, said Jack Hainline of Advance Trading Inc.

Short-dated new-crop corn and soybean options provide a workaround for such scenarios, enabling producers to secure some protection at favorable prices while still leaving open the possibility of capturing benefits from an extended rally.

In one example, Hainline said some of his clients bought July short-dated $5.40 corn put options in late February that were worth 10 cents at the time. December corn was trading around $6.00; by late April, prices topped $7.50. “Those puts lost money but holding them gave us confidence to not sell corn at $6.00.”

Continuing increases in trading volume and open interest in short-dated new-crop options reflect accelerating acceptance among farmers, grain processors, and others in the ag industry. Short-Dated New Crop options open interest – the number of outstanding contracts – reached an average of 190,000 contracts in May, while April's average daily trading volume (14,071) was up 30% from the same month in 2021.

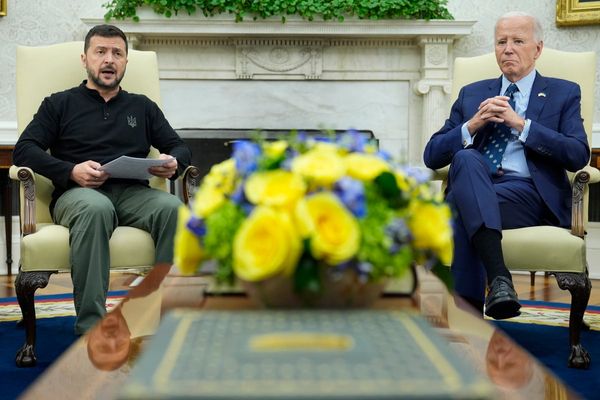

Russia-Ukraine Conflict and Other Geopolitical Disruptions

While grain prices have faded from steep, post-invasion rallies, the Russia-Ukraine war likely will keep markets on edge for the foreseeable future. Russia and Ukraine combined account for about 29% of global wheat exports and almost one-fifth of world corn exports.

Russia-Ukraine “will remain an uncertainty,” Hainline said.

Looking Ahead to 2023: Longer-Term Risks

Beyond the 2022 growing season and harvest, Huston sees energy and fertilizer as among the largest keys to U.S. farmers' production plans and income potential (fertilizer prices are linked to natural gas).

“For 2023, we are watching natural gas prices as an indicator of availability of nitrogen,” Huston said. “Cheaper natural gas prices could open up more production, but with current prices and supply chain disruptions, fertilizer suppliers cannot guarantee supply or price it to farmers. Russia being a big fertilizer supplier throws another kink in the chain.”

High grain prices won't stay high forever, Hainline added, meaning it's critical for farmers to consider hedging opportunities now.

“We’re actively looking ahead to 2023 and what tools we can use to hedge that crop,” Hainline said. “This has been a nice bull run in commodities. But the producer who comes out ahead isn’t the one who sold the last 10% of his 2021 corn crop at $8. It's the producer who has 2022 and 2023 hedged for if and when the market moves lower. We’re thinking about multiple crop years at one time.”

Ivers is pleased to see grain prices at levels that should generate favorable profit margins for farmers this year, but he’s also concerned about an inevitable market downturn – the best cure for high prices is high prices, as one old farmer saying goes. He, too, has an eye to 2023, noting he’s concerned about securing ample supplies of fertilizer and other inputs.

Current corn and soybean prices “are enticing,” Ivers said. “But you can’t overdo it either with your new-crop sales because there are no guarantees how much you’ll get. And there’s no weather factored into the markets, either. We could still have a drought. It’s all very unpredictable.”