Android is the most popular operating system in the world, has a huge and mostly open application ecosystem, and runs on thousands of different things. When it comes to security and user privacy that is the recipe for a disaster.

Add in the whole fragmentation thing, where there are several different versions of Android still in use and visiting Google's Play Store, all with different levels of system security features and it gets even worse. All Google can do is focus on fighting the problem on its own app store and through one of its own services.

That's where Play Store policies and Google Play Protect come into the picture. While it's not great that this can leave plenty of devices running Android — from Phones not using Google's services to hobby boards to TV boxes — out in the cold it is one area where Google is doing a pretty good job. The company even releases transparency reports to let us know how it's going.

The most recent report has some astonishing numbers that make owning a smartphone sound pretty scary, but what exactly does any of it mean?

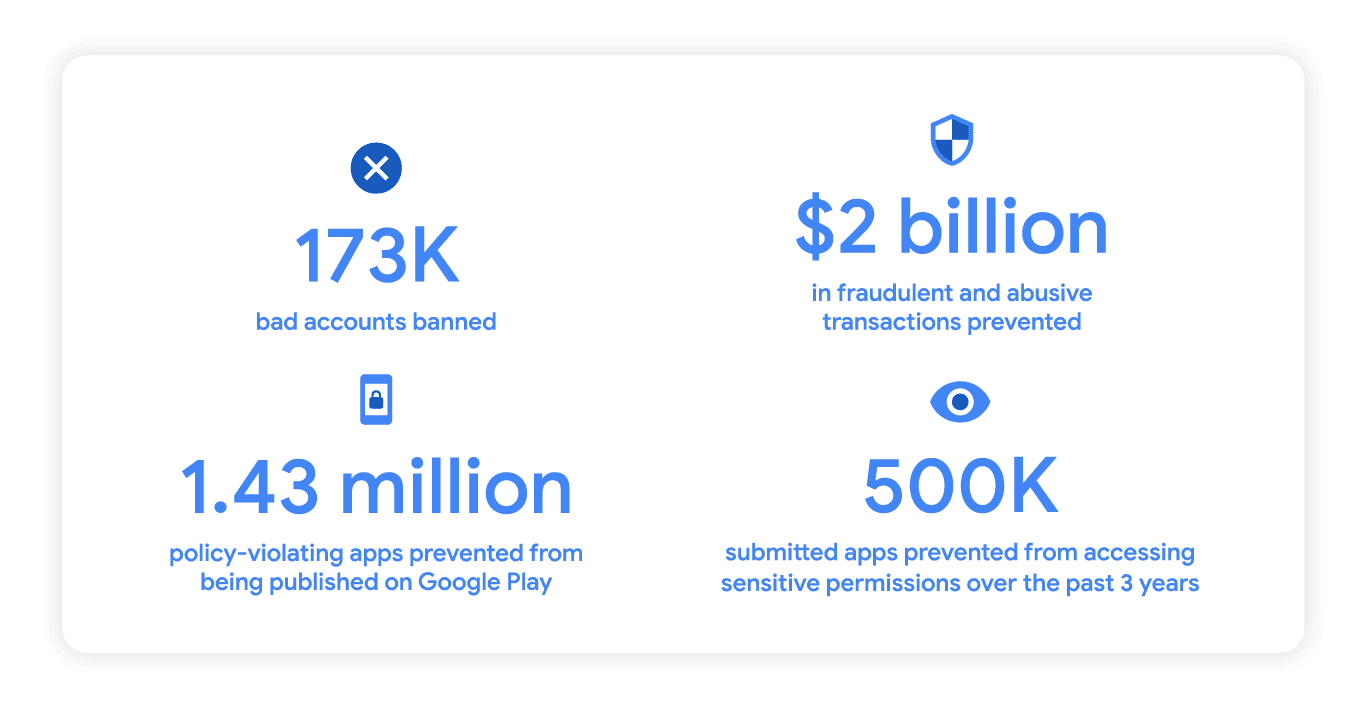

Google banned over 173,000 "bad" accounts.

Bad accounts is a pretty generic term, so what exactly does Google mean here? Google classifies a bad account as a developer account belonging to a person who is part of a fraudulent developer group, an app publisher working on behalf of a fraudulent developer group, or a fraudulent publisher group itself.

Writing apps can be hard work, but promoting them can be even harder. Many developers use an app publisher to get their work distributed and advertised so that you and I can find it and try it. Malicious developers can do the same thing, and those are the 173,000 "bad" accounts that got kicked out of the Play Store so they didn't end up in your phone in 2022.

Google prevented $2 billion worth of fraudulent or abusive transactions.

This doesn't mean what you probably think it means. Developers who try to cheat you or me out of our money are counted as one of those bad accounts mentioned above. This figure is about users trying to rip off developers.

A perfect example of this exists. Twitter users can pay for a month's worth of Twitter Blue and use a simple exploit to keep getting the benefits after canceling. No, I'm not telling you how you can use Google to find that out.

Google has what it calls Google Play Commerce to assist developers with taking payments and offering paid services, both one-time and subscription-based. Using Play Commerce APIs a developer can protect themselves from being cheated. Sometimes we are the bad guys.

1.43 million apps were not published because of policy violations.

Policy violations are a broad term that's easily defined. You can see the full list of Play Store developer policies here. They include things you expect to see like the prohibition of restricted or inappropriate content and the protection of user data.

These policies also include boring things like copyright and intellectual property provisions as well as things that serve Google's own interests like API target levels and SDK requirements.

Many of these policies are in place to protect users; does anyone really want hate speech or violent activities to be promoted through Google Play? Yes, some people do and those people have to find apps that do it from other sources. Google doesn't care what you install on your phone, but it does care what gets published on its app platform.

500,000 apps that could access sensitive permissions were blocked from being published.

Yes, a full half of a million apps were trying to steal your data. Except not really.

Writing an Android app is easy. Writing a good Android app is hard. Writing a good app that wades through the hundreds of APIs and methods available without getting at least one thing wrong is next to impossible.

This factoid doesn't mean Google blocked 500k malicious apps from making their way to Google Play. It means that Google and programs like the App Defense Alliance worked with developers to find ways to do the crazy and cool things apps can do without doing more than they needed to do.

Were some of these apps designed to steal data? Probably. Most of them though were apps that just needed a bit more refinement and another set of eyes to look over so the troubleshooting could find — and remove — permissions and methods that didn't need to be there.

It's good that Google tells us what it is doing to protect its app platform, its users, and its developers every year. The company does a good job spelling it out without being too nerdy with the language.

What's most important, though, is that we understand what it means so we know where and how Google can improve in 2023.