Gong were one of the great cult psychedelic rock bands. Founded in the late 1960s by Daevid Allen (who died in 2015), they charted an brilliantly eccentric course on the fringes of rock’s mainstream. In 2004, Classic Rock looked back over Gong’s unique career with Allen and former guitarist Steve Hillage.

When Mick Jagger knelt to receive his knighthood at Buckingham Palace in 2003, rock lost any pretence of being the soundtrack to revolution. But if the chief Stone is happy to become a member of the medal-wearing establishment, maybe he should take a look at another kind of ‘gong’: Daevid Allen, the self-styled ‘Alien Australian’ who is five years Jagger’s senior, but has lead these underground denizens on and off since the late 60s.

While there have been numerous changes of both line-up and musical direction over the year, Gong have grown into something more than just a band. Gong represent an ideal, a philosophy, a design for life that transcends the individuals involved. Allen has consistently claimed to be a channel through which Gong’s music – which he says has an independent existence – is brought to the audience. His work is imbued with ideas and concepts gathered from various (mostly Eastern) religious-belief systems around the world, but his approach to enlightenment fails to conform to any conventional structure.

Since the band first coalesced back in the late 60s, Gong’s almost non-stop revolving-door comings and goings of dozens of members – some staying for the long term, others just passing through – have seen the likes of Steve Hillage and Allan Holdsworth, Gary Wright (Spooky Tooth), Robert Wyatt (Soft Machine) and Tim Blake join the nucleus of Allen and poetess Gilli Smyth. The band have always enjoyed a fan base of people from a surprisingly broad musical spectrum, maintained through pro-active use of the internet, including many musicians from the stoner/trance scene, from Ozric Tentacles onwards, who freely confess a stylistic debt to Gong.

Three decades may have passed (and countless magic mushrooms consumed) since Gong’s Camembert Electrique album announced Allen’s presence in Britain, but his brain cells seem to be functioning as well as ever. Maybe that’s a miracle in itself, since Gong was the result of an acid-trip revelation Allen had back in 1965. At that point he was a poet living in Majorca, in the small coastal village of Deya, “playing a bit of jazz on the side” and interacting with poet and novelist Robert Graves – one of several influential characters to have featured in Allen’s life.

“It gave me very clear pictures of what was ahead,” he says. “I’ve never had anything like that again. Very extraordinary.”

After arriving in pre-Beatlemania Britain by boat from Australia, Allen’s first musical collaborators were Robert Wyatt, Hugh Hopper and Mike Ratledge, all of whom would go on to be members of Soft Machine, of which Allen was briefly a founder member. The group’s name was taken from the title of a controversial novel by William Burroughs, whom Allen had encountered while both were staying at Paris’s infamous Beat Hotel. Indeed Allen and avant-garde composer Terry Riley worked with Burroughs under the name The Machine Poets, in between earning a crust by distributing the New York Herald around the city by motorscooter; Riley instructed Allen on the use of tape loops, before the latter decamped to Deya where he later had his vision.

After his Soft Machine stint was terminated by the UK authorities on visa grounds, Allen went to Paris and undertook a series of gigs in Left Bank theatres, in which he, Gilli Smyth and a ‘floating’ cast of singers and musicians, played what he later described as ‘pure space music’, developing the ‘space-whisper’ vocals and glissando guitar technique (inspired by Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett) that would become fundamental to the Gong sound.

A recording – on the sound channel of a hand-held movie camera! – of the group’s appearance at the Amougies Jazz festival in Belgium in 1969 was later issued as the Magick Brother, Mystic Sister album. Soon afterwards the name Gong was first coined.

The student revolution in Paris in the Spring of 1968 had made Allen persona non grata in yet another country. Instead of hurling rocks at the police with everyone else, he had chosen the revolutionary alternative of presenting them with Teddy bears, reading poems and projecting a light show on to the clouds of smoke hanging over the barricades.

“Subsequently we were considered to be representing student anarchists,” Allen says, “and for quite a long time there was a riot everywhere we went.”

Learning of a warrant for his arrest, Allen sensibly legged it back to Deya the day before his apartment was raided and stayed there until the heat died down.

From the outset Gong had been a loosely defined collective, and numerous musicians, some now long-forgotten, passed through the band’s ever-changing line-up. One who stayed was Didier Malherbe, a seasoned jazz musician (discovered living in a cave in Deya) whose distinctive sax and flute playing became a vital piece in the band’s sonic jigsaw.

As things settled down, a flurry of activity saw Gong record a soundtrack album for the film Continental Circus and collaborate with poet Dashiell Hedayat on the now ultra-rare album Obsolete, while Allen also found time to record a jam-based debut solo album Bananamoon.

Many British fans got their first taste of Gong through 1971’s Camembert Electrique, regarded as the band’s first ‘real’ record. A stunning fusion of all that had gone before – the space whisper, glissando guitar, tape collages and humorous asides, unexpected changes in mood and texture, and a distinct jazz influence – Gong followed its recording with an appearance at that year’s Glastonbury Fayre.

But Gong was proving to be a hard way to earn a living. And after learning Gilli was expecting their child Allen decided to disband the group and concentrate on writing. The unlikely saviour of the day came in the shape of Richard Branson, whose fledgling Virgin Records made a splash by selling Camembert Electrique for a bargain 50p on the label’s Caroline imprint. “It was a pretty good idea, because it rose high in the British album chart,” Allen states.

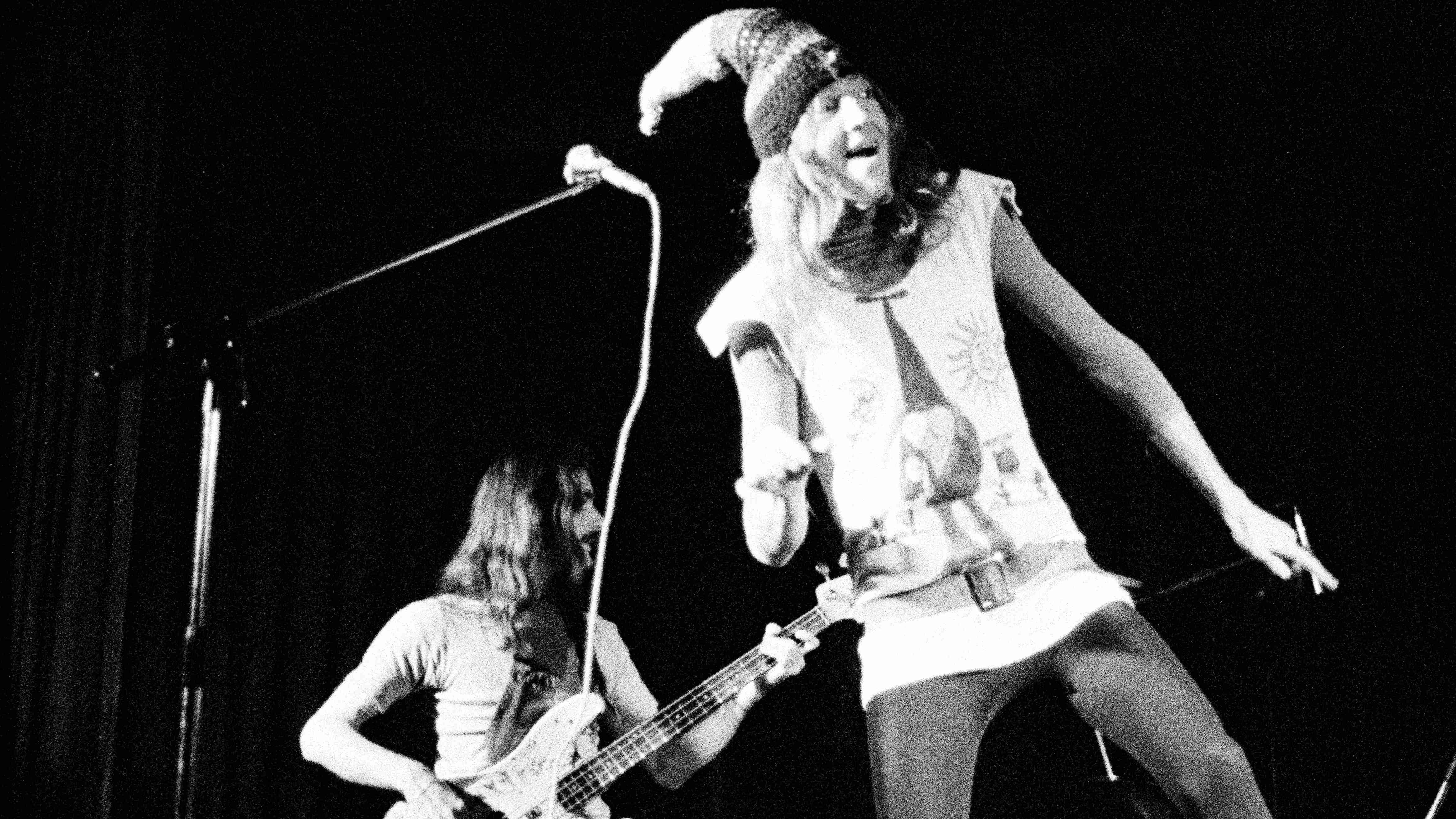

Virgin’s interest in recording new albums was enough to cause a change of heart, and Allen decided to revive Gong. In December 1972 the band went off en masse to see a French gig by Allen’s old Soft Machine colleague Kevin Ayers and his band The Whole World. When Didier Malherbe got up to play with them, the most impressed man on stage was Ayers’s guitarist Steve Hillage. Having felt confined by having to step into Mike Oldfield’s shoes in Ayers’s band, Hillage followed Didier like the Pied Piper and joined the Gong collective, where he perceived greater scope for developing his individual, spacey style. Thus began what Allen calls “the blissful, wild, peaking jamming of that particular time, the so-called classic mid-70s period”.

Hillage, something of a youthful prodigy, had got his first record deal at the age of 19 and formed the group Khan (whose drummer, Pip Pyle, had quit to go to France and join Gong – “I couldn’t really object, because I was a fan,” Hillage now laughs). “Daevid wanted to bring in fresh blood to the band and asked me to join. I became a full-time member in January 1973, not long before Gong signed their permanent deal with Virgin Records. Tim Blake [keyboardist] and I were the youngest members at that time.”

Also on board from early ’73 was Fiji-born bassist Mike Howlett, who, like Allen, had arrived in Britain via Australia. He was brought into the band on the basis of having the star sign Taurus. “We did actually jam together, but I had the impression it didn’t matter if I could play or not as long as the astrological signs were right,” Howlett says. Classically trained percussionist Pierre Moerlen eventually completed the rhythm section.

The so-called Mark III band recorded the ‘Radio Gnome’ trilogy of albums (The Flying Teapot, Angel’s Egg and You) that would come to be regarded as Gong classics. Those albums developed the philosophical ideas Allen had floated on Camembert…, reflecting his aim of spreading spiritual awareness and the attainment of a higher state of being. Drugs, and especially hallucinogens, played an inevitable part in this, but the aural trip was just as other-worldly. And if the lyrical content, expounding the ideology of Floating Anarchy, wasn’t your cup of strange-tasting herbal tea you could be transported just by the music.

But humour was always at the forefront of Allen’s mind as he told the story of Planet Gong, an idealised version of Earth on which the central character, Zero The Hero, met and interacted with the Pot Head Pixies (PHPs) and Octave Doctors, all the while listening to Radio Gnome Invisible, a kind of telepathic pirate station in your head. The band members embraced the spirit of things by adopting silly names like Hi T Moonweed (Blake), Bloomdido Bad de Grasse (Malherbe) and Shakti Yoni (Smyth). But Bert Camembert (Allen himself) was using humour with a purpose.

“My whole reason for making music is to be able to put a message over and have people experience it direct,” he explains, “rather than having them read about it or having someone tell them about it. The idea was to set up a giant workshop which people could get into by laughing or being silly.”

But the music itself was far from foolish, with Allen having cleverly surrounded himself with players technically better than him. Interestingly, both Allen and his musical lieutenant Hillage now pinpoint Angel’s Egg (1973) and You (1974) as the highlights.

Allen: “Angel’s Egg has got a tremendous diversity, a sort of smörgåsbord encompassing a wide range of styles and different political, sociological and spiritual attitudes. Then if you wanted to get the peak of the Hillage/Tim Blake period it would have to be You.”

Although it was all presented in an intentionally whimsical manner, the underlying beliefs were serious, and built Gong a considerable ‘alternative’ following. But the recording of You proved to be a traumatic experience. Allen’s ideas were under increasing attack from the other members of the band, especially as he had renounced drugs, and funds were frozen when contractual complications kicked in.

The history of Gong had taken many quirky turns over the years, but none so unexpected as the one in April 1975 that saw Allen hitch-hike away from a gig and out of the band completely. “It was the strangest experience, man,” he told an incredulous Melody Maker reporter, talking about a “force field” like a spongy rubber mattress that had prevented him from getting on stage. “Startled, I tried again. Still couldn’t make it, so I decided to go for a walk.”

Unlike his brief departure from March to May 1973, when the others had played on as Paragong, Allen was now out for good. The band not only played the gig without him, but also vowed to continue under the name. Though there was bitterness at the time, in retrospect Allen regards it as an evolution rather than an abandonment of his creation: “I think it was really great that it went on without me and without Gilli”.

He also admits he feared the consequences of fame. “To survive in the rock industry it’s better to limit your fame; I know very, very few people who’ve survived the fame trip.” The answer, he says, is “always to vanish, drop out. That’s another reason I left Gong at that time, because if I hadn’t it would’ve gone on to another level of people coming in with briefcases full of cocaine et cetera.”

In some respects Gong already had replacements for Allen and Smyth within the band, in Steve Hillage and his partner Miquette Giraudy. But these days Hillage insists that “for me, Gong without Daevid wasn’t Gong. After he left, Virgin Records put out a press release saying that I was the new ‘leader’. This made me feel very uncomfortable, and accelerated my own decision to leave the band.”

Hillage’s eventual departure, during the recording of Gong’s 1976 album Shamal, led to some marvellous Hillage solo albums that followed his Fish Rising from the previous year, recorded with the help of Gong members, which include the Todd Rundgren-produced L and Hillage’s first step into ambient music with 1979’s Rainbow Dome Musick.

“I suppose my post-Gong solo albums were a blend between what I started with Khan and what I discovered in Gong,” Hillage offers. “As the seventies progressed we became more influenced by funk and disco, which seriously confused the ‘progressive rock’ brigade. But Gong also had a funky side, as you can hear in tracks like The Isle Of Everywhere [from You]. The funk and disco influence, as well as early electronica like Giorgio Moroder and Kraftwerk, laid the seeds for System 7 [Hillage’s post-Gong dance act].”

In the absence of its two leading lights, the Gong name was picked up by drummer Pierre Moerlen, who subsequently took the music down a jazzy route that few original Gong fans were inclined to follow. Hillage agrees: “Despite my great respect for Pierre as a musician, the lateseventies jazz-rock direction didn’t really do it for me.”

Allen returned to Deya with Gilli and, by good fortune, was able to buy a house after a French TV station adopted 30 seconds of the Continental Circus soundtrack as a news theme. Allen and Gilli also each recorded solo work, before returning to England to form Planet Gong, taking over a hitherto unknown new-wave group called Here & Now. Since then, Allen’s musical projects have included New York Gong, The Divided Alien Playback Band and Gongmaison, while Gilli Smyth has released several albums with her own group Mother Gong. Allen highlights Shapeshifter, recorded in 1992 without Smyth but with Malherbe and ex-Gong drummer Pip Pyle, as significant: “It has a funny bridging quality to it; there are some really interesting parts.”

1994 saw Gong’s 25th anniversary (measured from Magick Brother, Mystic Sister), which was celebrated with two gigs at London’s Forum, which showed that the spirit of Gong was still alive and well. Allen singles out the performances of the reunited ‘Radio Gnome’ band and more than a dozen spin-off groups to ecstatic audiences as the one incident that ranks alongside “the demented gigs back in the 70s as a career highlight”. The only two major members of the family missing were Steve Hillage and Pierre Moerlen, the latter allegedly playing in a pit band for a stage production of Evita in Sweden.

The 1990s saw the arrival on the scene of musicians who, in their formative years, had been influenced by Gong. It kick-started another phase in the band’s career, as Allen returned to regain control of the Gong legacy and destiny. “I think the fact that Gong still is the band you listen to when you smoke your first joint or drop your first acid trip at school has served us extremely well over the years,” he laughs. “It’s enabled people to understand the unusual drifts that we’re trying to pull.”

Having released 1992’s Shapeshifter and 2000’s Zero To Infinity, Gong have embraced modern technology, utilising the internet to spread the word. “The net is made for bands like Gong,” Allen says. “Our audience is scattered about all over the world. They’re not a certain type of person but an across-the-board sprinkling, so it’s the only way you could find them; you would never find them by advertising in a magazine or newspaper, even Classic Rock.”

In 2000 Allen decided to take a break from Gong and spent much of his time in the States, working with a band called University Of Errors. “They’re a psychedelic rock band from San Francisco, and it’s a funny angle,” he says. “Like John Coltrane said: there’s no such thing as an error, there is only a new idea. And the band was basically built around this notion. It’s all to do with not being perfectionist, but making mistakes.”

In 2004, Allen’s benevolent Gong dictatorship continues – much to Steve Hillage’s delight. “I’ve seen them on several occasions and I’ve really enjoyed it,” the guitarist says. “They attract a really good crowd of both young and old and they’re putting out a really good energy. All power to them.”

So what of Allen’s initial acid-trip vision in 1965, nearly four decades ago – has everything gone to plan so far?

“Yeah, it has. Except for one bit at the end that hasn’t come yet. We were all gathered in a house somewhere; it could be Australia or perhaps Spain or the South of France, because it was very sunny and very bushy; or it could be down in the West Country. And we’re all gathered there and there was just this sense of completion about the whole thing. And it hasn’t happened yet.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 63