Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell dropped a major hint this week on the central bank's plans to end the longest stretch of high interest rates on record.

However, the hint wasn't tied to the path of inflation pressures.

Stocks have been rising for much of the past four months, booking a series of record highs and extending the S&P 500's year-to-date gain to around 17%. The heady returns were built on the back of outsized gains for megacap tech names, improving corporate earnings, and bets on an autumn Fed rate cut.

In an inflation fight that began shortly after prices spiked in the postpandemic era, the Fed lifted its benchmark lending rate to a 22-year high of around 5.375%. Its last hike was nearly a year ago when headline inflation ran at an annual rate of 3.2%.

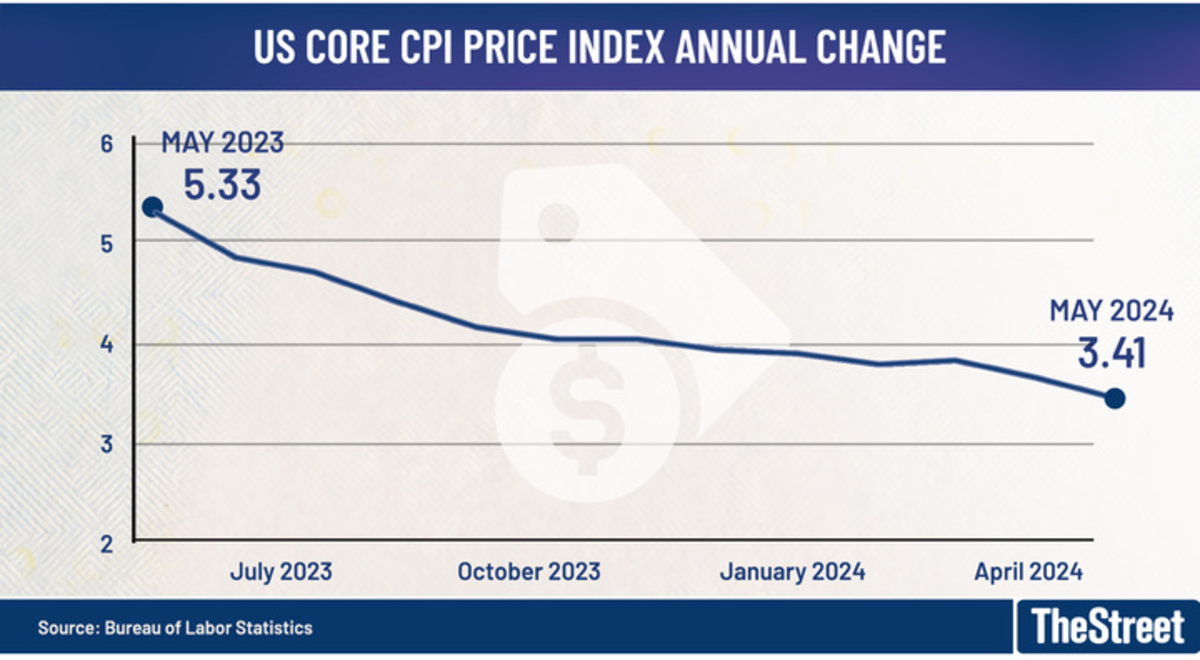

Bureau of Labor Statistics

Since then, inflation pressures have remained frustratingly difficult to tame or predict. They rose as high as 3.7% in November and fell to as low as 3.1% in January, tallies that in both cases remain well north of the Fed's preferred target of 2%.

Economists expect the Commerce Department's June Consumer Price Index reading to show headline CPI inflation rose at an annual rate of 3.1%, which is not terribly different from last year's level. Core prices are estimated at an annual rate of 3.4%, roughly where they were in May.

Getty

That won't be enough for the Fed to signal a near-term rate cut, particularly given that it's warned about so-called inflationary base effects that are likely to deliver modestly higher readings over the second half.

The Fed's subtle shift from inflation focus

But Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has instead subtly shifted the market's focus from the stubbornly sticky inflation readings to the recent weakness in the job market, suggesting that this may be the key to unlocking the central bank's next rate move.

“Elevated inflation is not the only risk we face,” Powell told lawmakers on the Senate Banking Committee Tuesday as part of his semiannual testimony on Capitol Hill.

“The latest data show that labor-market conditions have now cooled considerably from where they were two years ago," he added. "And I wouldn’t have said that until the last few readings.”

Related: Top Wall Street analyst issues stark warning for stocks

On its face, it's hard to see where that weakness comes from: The Labor Department reported last week that around 206,000 new hires were added to the economy last month, a stronger-than-expected result that lifted the 2024 total to around 1.4 million.

However, revisions to prior-month tallies took around 111,000 jobs back, according to Labor market figures, and the headline unemployment rate nudged past 4% for the first time in more than two years.

Two-sided risks face the economy

Broader economic growth is also slowing, with the Atlanta Fed's GDPNow tool suggesting a second-quarter pace of around 1.5%, just barely ahead of the 1.3% gain recorded over the year's first three months.

Mindful of that slowdown, Powell told lawmakers that the economy faces "two-sided risks," both of which are tied to Fed decision-making.

"If we loosen policy too late or too little, we could hurt economic activity," Powell said. "If we loosen policy too much or too soon, then we could undermine the progress on inflation. So we’re very much balancing those two risks."

Related: Analyst revamps S&P 500 target ahead of CPI inflation report

That likely puts the next round of job market data, including the June Jolts report, the July nonfarm-payrolls update, and corporate layoff figures from Challenger Gray, in sharp focus and leaves inflation readings secondary over the coming months.

"After two years of focusing on inflation, the Fed is talking more about the labor market and has acknowledged that any unexpected labor market weakness could prompt them to cut sooner," said Lauren Goodwin, economist and chief market strategist at New York Life Investments.

"(But) what we’re seeing today is not an unexpected weakness in the labor market – everything is still fine," she added. "We believe the earliest the Fed can cut is in September, and we believe the Fed will be attentive to reasons to make the pivot at that time."

The Fed's Jackson Hole meeting could be key

The Fed will meet on July 31 in Washington to unveil its latest interest rate decision. Few, if any, market participants expect a change in the current Federal Funds Rate, which sits between 5.25% and 5.5%.

However, Powell's next major event could provide the market's clearest signal for a rate move in September, upon which CME Group's FedWatch places a 74% chance of a quarter-point reduction.

The Fed chairman will give his keynote address at the central bank's annual economic forum in Jackson Hole, Wyo., on Aug. 22. Powell will then be armed with deeper jobs data and the July PCE inflation report.

"We still think the Fed already has waited too long and soon will be rushing to stop a major downturn," said Ian Shepherdson of Pantheon Macroeconomics. "We expect a clear signal from the chair at the Jackson Hole symposium in late August that rates need to be reduced at least once this year."

More Economic Analysis:

- June jobs report bolsters bets on an autumn Fed interest rate cut

- Biden debate flop boosts Trump, but economy may be tougher opponent

- First-half market gains come with a dash of investor unease

That would still likely disappoint markets, given that traders are forecasting at least two cuts this year, along with a host of further reductions in 2025. The cuts would support the rally in stocks and drive the S&P 500 closer to the 6,000-point mark.

Goldman Sachs analysts revamp outlook

It could also leave the stock market on what Goldman Sachs's Scott Rubner calls "correction watch" after the 36 record highs that the S&P 500 has produced this year.

Noting that August equity-market flows are typically the slowest of the year and that markets have historically retreated from mid-July highs, Rubner argued in a note published this week that he's modeling for a "late summer equity market correction" if earnings disappoint and investors begin to focus on the autumn election results.

Generally, a correction is defined as a decline of at least 10%.

LSEG data suggest collective second-quarter profits for the S&P 500 are likely to show a 10.1% rise from the year-earlier period to a share-weighted $492.8 billion, a tally about $5 billion lower than earlier forecasts.

For the whole of the year, analysts see earnings rising 10.6%, with a further 14.5% gain in 2025.

“The pain trade has shifted from the upside to the downside,” Rubner said. “The buyers are full and running out of ammo after the best trading days of the year are now behind us.”

Related: Veteran fund manager sees world of pain coming for stocks