When Gloria Steinem and I speak, five days ahead of the midterm elections, she has already cast her ballot. “I’m glad I voted by mail, so I’m sure that my vote is in there,” she says. We’re talking on the phone, Steinem from Manhattan’s Upper East Side in New York City.

She has resided in the area since 1966, when she was 31 and at the beginning of a career that would make her one of the foremost figures of American feminism. Roe v Wade — the landmark Supreme Court decision that guaranteed a woman’s federal right to abortion — wouldn’t be published for another seven years, in 1973. The decision stood for most of Steinem’s life. Then, in June of 2022, about three months before our conversation, the Supreme Court overturned it, triggering full and near-total bans in several states.

That moment “didn’t come as a total surprise” to Steinem, because “the manipulation of who is and is not on the Supreme Court has been clear for a very long time”.

“There had been many warnings,” she adds, “but I’m not sure that the importance of who is on the Supreme Court was absorbed into the public consciousness as not just a legal issue, but also a social justice issue.”

It feels like a particularly pertinent time to speak with Steinem, who over the course of her career fought for many of the liberties that are now under threat. Abortion-related measures are on the ballot in five states: California, Vermont and Michigan are considering updating their state constitutions to reflect the right to an abortion; Kentucky is considering a change to its constitution to effectively ban abortion outright for the state’s residents; and Montana is weighing a bizarre “Born Alive” bill that seeks to infringe further on women’s reproductive freedoms.

Yet, Steinem speaks with resolute optimism about the future. She was “heartened” by a recent report in Ms Magazine, the feminist publication she co-founded in 1971, according to which the fight for abortion rights and equality is driving young female voters to the polls. “Our rights over our own physical selves have not usually been enunciated as what’s on the ballot, and for obvious reasons, women especially realise that,” she says. “So I’m hoping this will have a big impact.”

A high turnout across all categories of voters is Steinem’s main hope in the lead-up to election day. Voter turnout remains lower in the US than in at least 30 other countries, including India, France and South Korea, according to the Pew Research Centre. This is a “fundamental problem” to Steinem, because, she says, “if we don’t vote, we don’t exist”.

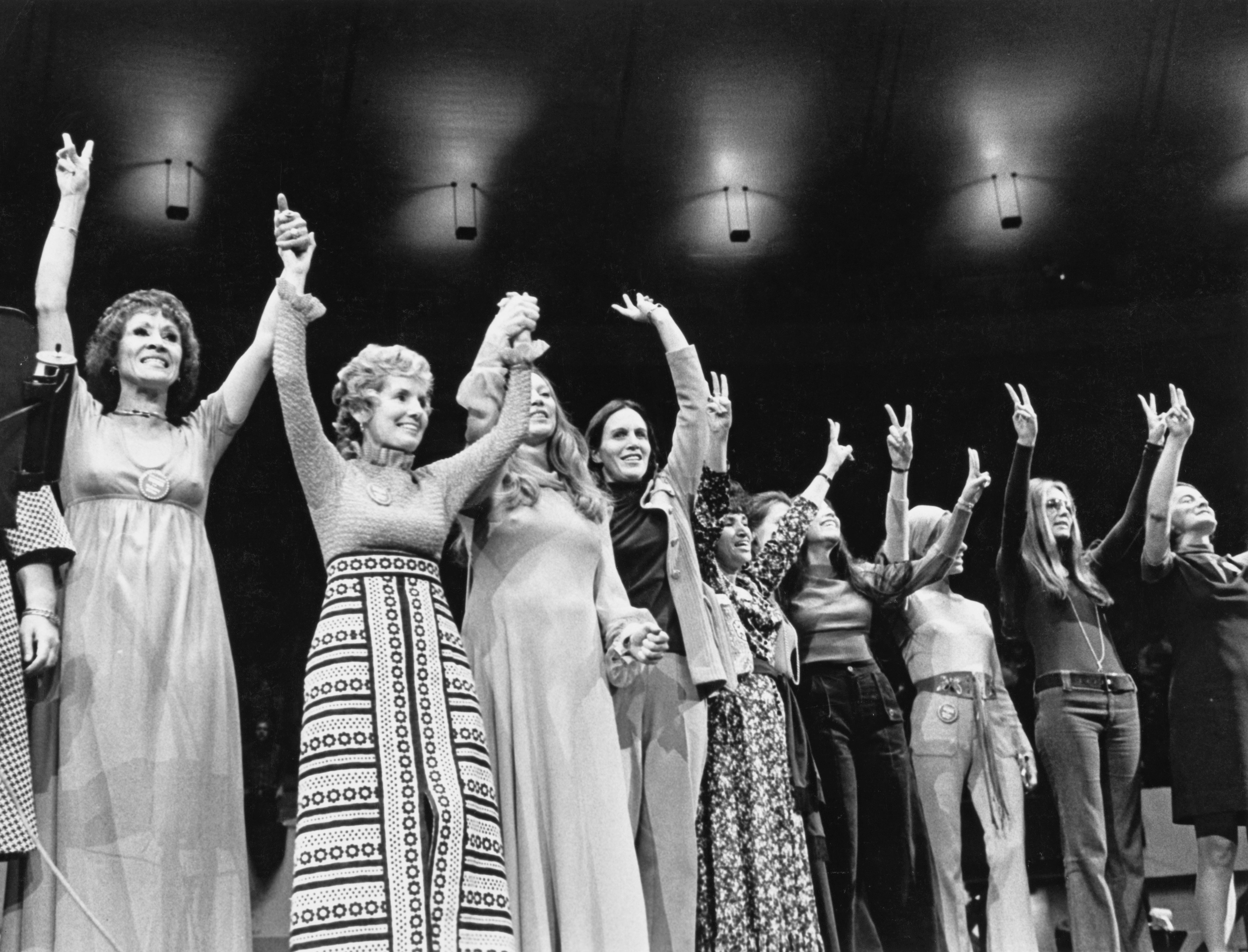

Steinem began her career as a freelance writer in the 1960s, after spending a couple of years in India on a fellowship. One of her breakthrough pieces was a 1963 exposé on the treatment of women hired to work as Playboy Bunnies – an assignment Steinem conducted undercover, after being hired as a Bunny herself. She was a speaker at the historic 1977 National Women’s Conference, a turning point in the movement for women’s rights. On her website, she describes herself as “a writer, lecturer, political activist, and feminist organiser”. She is the author of several books, including a biography of Marilyn Monroe, the collection The Truth Will Set You Free, But First It Will Piss You Off!, and the 2015 memoir My Life on the Road.

The latter was dedicated, poignantly, to the doctor who referred Steinem for an abortion in 1957, when she was 22 years old, who told her: “You must promise me two things. First, you will not tell anyone my name. Second, you will do what you want to do with your life.”

“Dear Dr Sharpe,” Steinem wrote in the book’s dedication, “I believe you, who knew the law was unjust, would not mind if I say this so long after your death: I’ve done the best I could with my life. This book is for you.”

Steinem has long written about, and spoken of, the ties between authoritarian regimes and the removal of women’s reproductive rights. “The power to make decisions about our own bodies is the first step towards democracy, so it comes as no surprise that authoritarian regimes resist our right to reproductive freedom,” she wrote on Instagram in October. During our conversation, she says she wishes this were more frequently taught in history, political science, and government courses: “Because we still view government and political change through a somewhat patriarchal lens, we miss the fact that authoritarian regimes tend to start that way.”

It’s a theme Steinem explored in an NPR interview last year, during which she was asked about “people who argue against abortion rights”, who would “be shouting at their radios” hearing Steinem defending them. “Well, then they don’t have to have an abortion,” Steinem replied. “They just can’t tell somebody else what to do.”

Why, I ask, does Steinem think people are swayed by anti-abortion rhetoric? “I’m not sure,” she says. “I think we have to ask each individual. But it seems to be a mix between a focus on the embryo as the most important entity, which is a kind of romanticised or mythologised response – which does not get interpreted as more care, or, say, free medical care for pregnant women. That doesn’t happen. And it seems to be partly about control, and partly about a traditional view of women’s rights and responsibilities.”

In that same NPR interview, Steinem brought up the need to “change who’s on the Supreme Court so it represents the country”. “The manly men on that court are never going to have to make [the decision of whether to get an abortion],” she added. “It’s not their decision. It’s not their bodies.”

During our call, she says it will “require a lot of thought to figure out if there is a more democratic way of appointing the justices”. “I don’t know if there should be a change in the way the justices are selected, so that they represent the population rather than who happens to be in the presidency, like Trump,” she says. But to her, the need for a change has been “clear for a long time” – “ever since the Civil Rights era, and how long it took for the court to represent the need for equal rights, and how long the racist legislation of the South was allowed to endure.”

I ask Steinem how she feels about the fact that we are discussing the same topics that made headlines during the founding of Ms Magazine half a century ago. “I think we would’ve been dismayed and alarmed to see where we are now, 50 years later,” she says. “But that was naivety too. We were thinking about democracy and not understanding patriarchy as the underpinning of the democracy we have. … If we can’t have decision-making power over our own bodies, we’re definitely not living in a democracy.”

Without taking away from the urgency of our present moment, Steinem has seen some improvements over the course of the past decades. When I bring up domestic violence, she remembers that “there wasn’t even a term” for it when she was growing up in Toledo, Ohio. “If police came to the scene, their goal was to get the couple back together again. That was their idea of success. There were no shelters, for instance,” she says. “So I do think that we have progressed, but we still are at best supporting the victim, and not punishing or trying to change the victimiser.”

In March 2020, Steinem shared on her Instagram account a Ms Magazine cover dating back to 1975. Back then, she wrote in her caption, “the phrases ‘battered woman’ and ‘domestic violence’ were just entering the language, and the women’s movement was organising the first shelters, and pressing for the first police responses and laws.”

“Now, the frontier is realising that domestic violence is the most reliable indicator of all violence – in the street or military violence against another country – because it normalises the idea that violence is an inevitable or an acceptable way of solving conflict,” she wrote. On the phone with me, she echoes this thought, calling domestic violence a “huge indicator of what’s to come” in the perpetrator’s life and of “the need to dominate”.

Because Steinem has been such a trailblazer, it is tempting to ask her what she’d say to the next generation of activists who are preparing to fight for their own rights. But, as it turns out, she’d rather listen and be of service: “What I would say to them is just, ‘How can I help?’” she says. “They know their shared life experiences better than I do. I just want to express a generational help.”

When I ask Steinem how she feels about the strange, reactionary turn America has taken of late, she once again reverts to optimism. “I feel hopeful, by decision or by rebellion, you know? Because hope itself is a form of planning,” she says. “If you don’t hope, you don’t formulate a possibility and you confer reality on the status quo, or even on your fears … If we don’t envision what we wish for, then we’ve given up a certain power.”