A glitch could be seen as a contemporary phenomenon. It might be the split-second freeze on a Zoom call. Or the iridescent warping of an iPhone display that develops around a crack in its screen. But glitches also pervade analogue technology, and they have inspired artists for over a century. Glitch: The Art of Interference, a new group exhibition at Germany’s Pinakothek der Moderne, brings together a host of cross generational names. The emotional and political potential of interference is explored in intriguing detail by the likes of Man Ray, Pipilotti Rist, and Nam June Paik.

In Freischwimmer 52, Wolfgang Tillmans pushes the limits of photography and presents a chemical tide of deep green; to make Queering the Dragset, Jake Elwes disrupted and retrained a digital facial recognition system with 1000 gender fluid and drag portraits found online; Arthur Jafa’s single-channel film Yellowjacket shows a man lying on the pavement as people walk past.

The exhibition developed out of curator Franziska Kunze’s long-held fascination with glitches in analogue imagery. “I am interested in looking at the surface instead of looking through it,” she says. “Interference, disruption, and failure make us so active. Otherwise, we’re just sitting there consuming. I hear this a lot from people who play computer games, where glitches play a big role. Once they appear, the gamers become more active and start to make use of them. I was interested in how failure or disruption makes us more creative.”

Many of the exhibition’s contemporary artists use glitches to challenge the systems that control us. The glitch offers a moment of awakening, enabling the user to see behind the primary structure or system and question its apparent omnipotence. “It’s a lot about changing perspective,” says Kunze. “Many of these artists are thinking outside the binary. If you think of digital images, they come from the binary system of 0s and 1s. In our culture there are also a lot of binary systems, even though so many people contradict them in the best way possible.”

These momentary slips or ‘mistakes’ also question the role of the artist. The makers of these works are responsible for planning the glitch, but the end result is often left to chance. “We are still living in a society that thinks so much about perfection” says Kunze. “This whole project is about embracing the failure and overcoming rules, systems, regularities, doctrines, and normative thought patterns. I think artists like to lose a bit of control.”

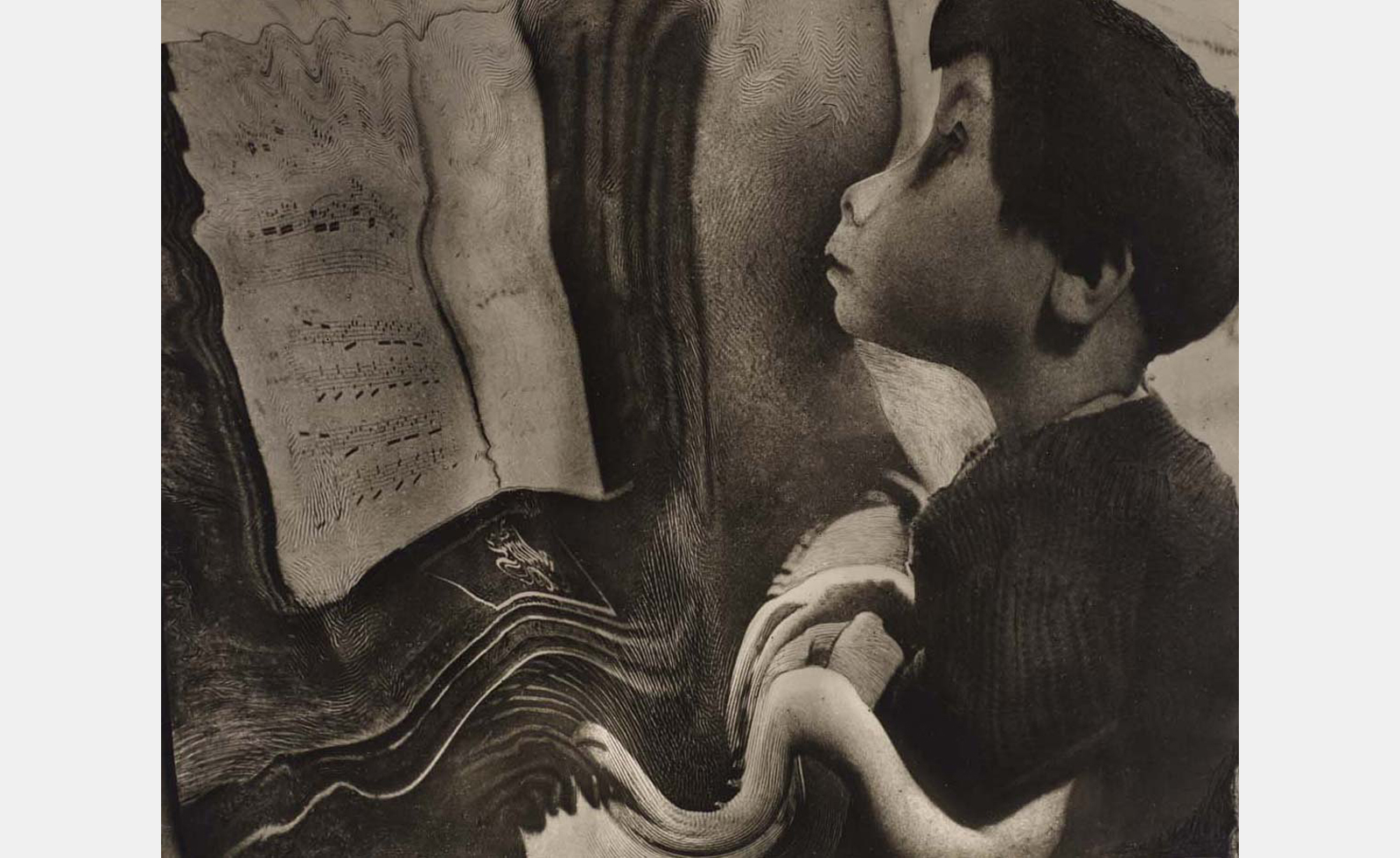

While the exhibition explores contemporary technology such as gaming software, digital video and audio, Kunze has looked back to the 19th century, highlighting the abstract nature of chemical slippages and light leaks on early photographic material. “When you look at how photography was developed, it was very different from what we think a photograph should look like or do,” she says. “It was more like a photochemical soup on top of light sensitive layers, but it was not shaping an image.”

There is something undeniably appealing about glitches. Analogue photography carries with it a sense of nostalgia and artistic intrigue precisely because it’s so prone to imperfections. There is a magic and fascination that surrounds the idea of glitches, whether in the mysterious orbs that used to appear in Victorian ‘ghost photography’ or the graphic errors in computer game programming. “There is a lot of wonder going on,” says Kunze. “I see it every time I walk through the exhibition.”

Glitch: The Art of Interference is on at Germany’s Pinakothek der Moderne until 17 March 2024