Continuing to prioritise economic growth is not a recipe for being a good ancestor. Nor is it a recipe for human progress, writes Jack Santa Barbara.

A large and growing number of scholars from many disciplines, are advocating for a reorientation of our social and political priorities by abandoning economic growth as our overriding priority.

Even some progressive economists are making these arguments. This degrowth movement argues for prioritising genuine progress in terms of both human wellbeing and ecological sustainability. Indeed, these scholars argue that abandoning economic growth is essential for achieving these more important objectives.

While recognising the need for social and economic change, others, mostly economists and business leaders, argue that economic growth is essential to achieve human wellbeing and ecological sustainability. They cite examples of green growth with clean technologies as pointing the way forward.

Obviously, both groups cannot be right; their views are mutually exclusive. Green growth and degrowth cannot both provide a guiding framework for a just and sustainable future. Which is most likely to be helpful?

Given the extent of our disruption of natural systems at a planetary level, our rapidly worsening social and political problems, and the growing investments in green growth technologies, this seems an important question.

Are we basically on course with the green growth, technology-driven initiatives that most major governments have embraced? Or do we need a radical rethink of our priorities and how we organise our economies and societies, as degrowth advocates argue?

Green growth is a more comforting option, as it implies we can continue pretty much as we are, and largely rely on technology to do the heavy lifting to clean up our environment, and deliver wellbeing in all its guises.

The more radical degrowth option is less comforting because it involves the unknown and many changes, some of which may seem unappealing at first sight.

Despite its appeal, what’s most comforting isn’t always what’s best for us.

There are now many thoughtful and scientifically based critiques of the dominant green growth approach. The essence of these critiques is that biophysical limits indicate that technology-driven green growth cannot deliver what it promises.

As conceived, green growth may well worsen environmental and social problems rather than alleviate them. Building out a clean, renewable energy system, for example, would require a quantity of fossil fuels that would create more emissions than our targets would allow.

Several critiques identify our dominant economic growth paradigm as the culprit in obscuring the flaws in the green growth approach, and the major obstacle to achieving the goals that both approaches share.

Because the degrowth scenario is less well understood, let’s focus on what it is and what its benefits might be.

The term “degrowth” is intentionally provocative, to shock us into at least giving serious thought to the role economic growth might play in our future. Degrowth involves much more than reducing economic activities to sustainable levels, for it includes many progressive policies and programs that would have broad appeal if understood.

The degrowth critique of economic growth acknowledges that economic growth has provided many benefits in the past. But the present is not the same as the past. The growth paradigm has been so successful that its (largely ignored) downsides now overwhelm planetary systems and exacerbate social inequities.

The way we measure economic growth is seriously flawed. We need to consider the drawbacks of economic growth as well as the benefits to provide a more comprehensive assessment of its net effects.

Economic growth is measured in terms of growing Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The term “Gross” tells us it measures all economic activity, regardless of whether that activity benefits people or the environment. GDP counts the monetary value of undesirable activities like cleaning up oil spills, clear cutting forests, automobile accidents, health costs for lifestyle diseases, and public expenditures for incarcerating offenders, for example.

In many cases the undesirable effects of economic growth are not even counted in GDP. These are the so called “externalities” such as species loss due to deforestation, greenhouse gas emissions, or human health problems from pollution.

In doing so, GDP confounds both the desirable and undesirable impacts of economic activity. Seeking GDP growth as a national goal is like a business adding its expenses to its revenue each year, and seeking to increase the total year after year.

These problems with GDP are not minor. Both climate change and biodiversity loss are negative costs associated with our level of economic activity. Both represent existential threats to human wellbeing and any notion of progress.

So GDP is hardly a good measure of “progress.” Yet our governments strive for more of it each year.

In discussions of the tension between GDP growth and environmental protection, the comment is often made that we need more economic growth to invest in cleaner technologies to protect the environment. Growing the economy to pay for the environmental damages associated with growing the economy, is a bit like an alcoholic having a morning drink to relieve a hangover.

There are multiple problems with GDP growth as a priority. Economists who developed GDP during WWII explicitly said GDP was not a good measure of social wellbeing, because it confounded desirable and undesirable activities.

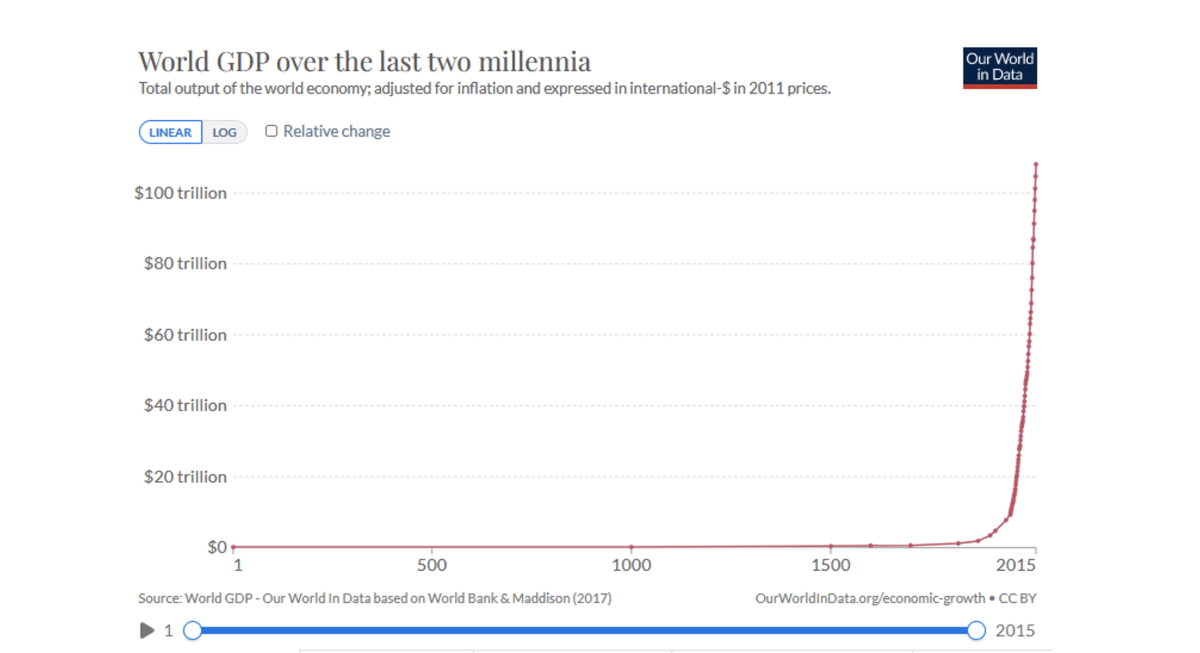

We also know that despite today’s global economy being at least 30 times larger than it was just a century ago, wellbeing and happiness have not followed suit.

GDP also fails to measure many unpaid exchanges that make life worthwhile in the care economy, largely provided by women. Without the care economy the financial economy could not function.

There is no denying there have been many material benefits associated with this explosion of economic growth. There is denial, however, about the costs associated with this level of economic growth, in terms of both increased inequality and ecological degradation.

In addition to being morally corrupt, a high level of inequality is a major obstacle to a well-functioning society. And our current level of ecological degradation is global in scope and threatens the wellbeing of all living things.

Both of these unaccounted costs are a direct consequence of our elevating economic growth above all other policy priorities. Continuing to prioritise economic growth is not a recipe for being a good ancestor. Nor is it a recipe for human progress.

The idea that human progress means increased economic growth leading to increased material consumption, is a relatively new idea in historical terms. That idea was energetically promoted by the marketing and public relations industries at the beginning of the last century in western nations, with considerable support from governments. Promoting consumerism was, and continues to be, a highly successful program with global annual expenditures of $ 1 trillion per year.

Previously, the focus of economic activity was to meet basic needs – adequate shelter to protect us from the elements, enough food to avoid malnutrition and starvation, health services, safe transport options, escape from drudgery, enough leisure to pursue personal interests, and participation in group decisions.

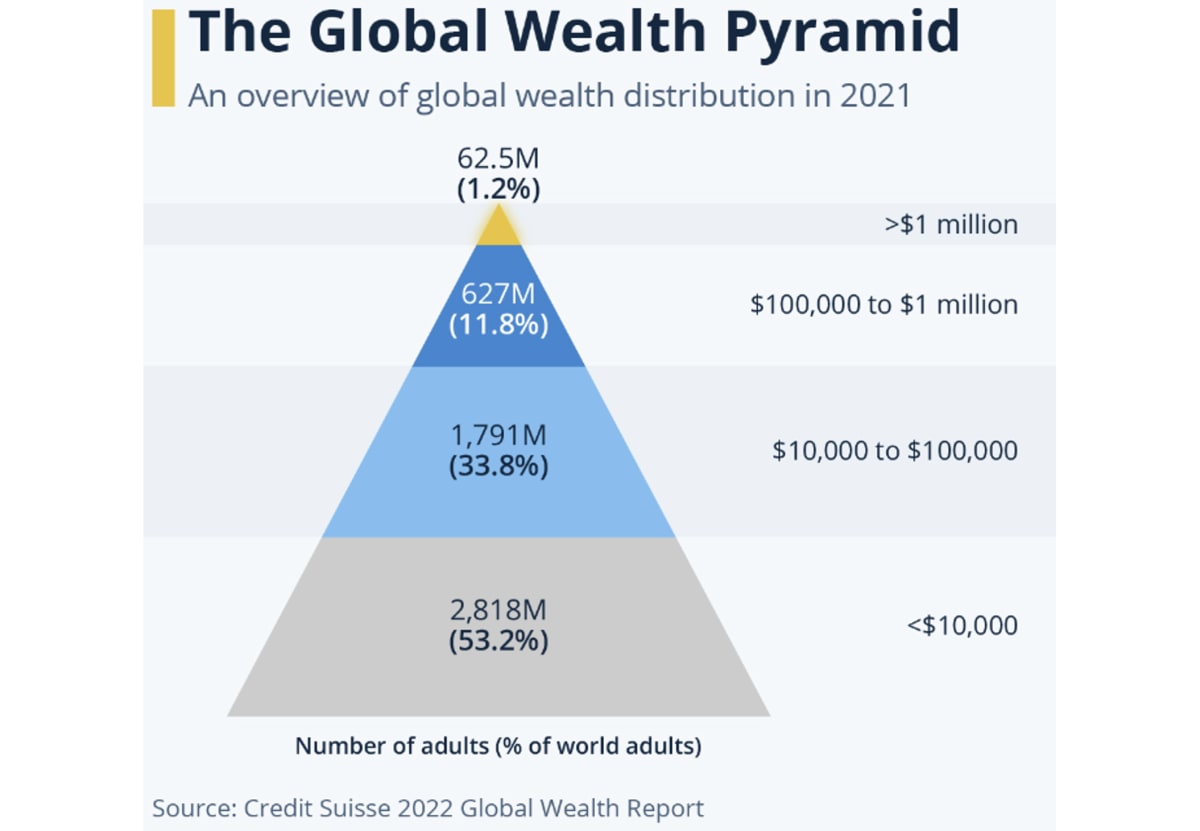

The acceleration of economic growth over the last century allowed for those basic needs to be met for many, but not the majority, of people. Indeed, economic growth benefits the relatively few rather than the majority.

Security regarding basic needs remains elusive for billions of people today despite the incredible growth of the global economy. If progress based on economic growth is, at a minimum, supposed to meet basic needs for everyone, then it has failed. Yet we continue to pursue it as our overarching priority.

The Degrowth Option

A wide range of progressive initiatives, policies and programs are being promoted by degrowth scholars from many disciplines. While they come at the major challenges we face from different perspectives, there is a convergence around two priorities – ensuring basic needs are met for everyone, and protecting the biosphere that nourishes and protects us.

The degrowth movement is receiving increasing mainstream attention. It has recently been referenced in some of the latest UN Reports on climate change and biodiversity, for example.

The idea of degrowth is sometimes criticised as being dull and unappealing, suggesting lives with degrowth would be primitive and uninteresting. The degrowth literature clearly suggests otherwise.

Degrowth would require a significant expansion of creativity and innovation in the social and economic spheres. And given its focus on creating conditions that are known to increase wellbeing and life satisfaction, degrowth living will be anything but dull and boring.

The degrowth movement is much more than simply a critique of economic growth. It contains a range of constructive social and ecological initiatives that, if implemented, would significantly contribute to a better life for most of humanity.

Think for a moment, what life would be like if we all had security regarding housing, health care, education, nutritious food, and meaningful work, and a full range of public services.

Think of what life would be like if we all could work fewer hours each week and have more time for leisure and personal interests.

Think of what would life be like if there were health and green job guarantees, so that everyone could have the opportunity of contributing to restoring the beauty and productivity of the natural world, and caring for each other in a dignified manner.

Think of what life would be like if there were reduced production of less necessary goods such as private jets, military equipment, mass produced meat and dairy, fast fashion, advertising, large private vehicles and luxury yachts.

Think of what life would be like if we took the climate emergency seriously and implemented a controlled reduction of fossil fuel use over a decade.

Think of what life would be like if housing were prioritised as a basic need rather than an investment opportunity.

Think of what life would be like if there were no more perverse subsidies going to fossil fuel and automobile industries, and there was a progressive wealth tax, the funds from both redirected to some of the above programs.

The degrowth movement is fully aware that simply abandoning economic growth and reducing the energy and material throughput of an economy would create great hardship without adequate supports in place. A significant part of degrowth thinking is precisely about ensuring these supports are available.

The dilemma we have is that our current economic system cannot function without growth. Even slow growth can be a problem in terms of employment and bankruptcies. And declining economic activity is a disaster within the existing system.

But degrowth is totally different from a recession or a government austerity program. It involves a carefully planned and managed reduction of less necessary and undesirable economic activities, and increase in activities supporting wellbeing and living within planetary boundaries. Degrowth is about reducing energy and raw material use to sustainable levels, and improving the quality of life for all.

Degrowth proposes changing the system so that economic growth is no longer needed to satisfy human needs and support human aspirations. A sustainable level of economic activity would still be needed, but at a much lower level of energy and material throughput. Our current system is way out of balance and degrowth aims to rebalance priorities on human and ecosystem wellbeing. Hence the types of initiatives summarised above.

The current economic system is simply not working, neither for protecting the natural systems that nurture us, nor for generating wellbeing for everyone.

Degrowth offers a desirable and workable alternative.

Doesn’t that sound like genuine progress?