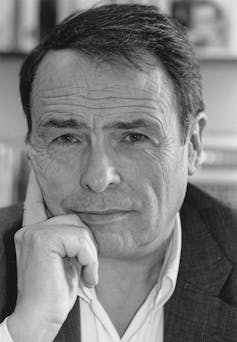

It is 50 years – two generations – since then Immigration Minister Al Grassby launched the idea of a multicultural Australia at a Melbourne conference in 1973. Ghassan Hage, Professor in Anthropology and Social Theory at the University of Melbourne, and currently visiting scholar at the prestigious Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle, Germany, has become the most significant intellectual commentator on multicultural Australia of the second of those generations.

The Racial Politics of Multicultural Australia – Ghassan Hage (Sweatshop)

The publication of The Racial Politics of Multicultural Australia by the Sweatshop Literacy Movement represents a significant collaboration. Hage is an Australian Arab immigrant, whose forebears came to Australia in the 1930s and settled in Lithgow, where they established a clothing factory. Sweatshop is an urban political project created in western Sydney by a younger generation of Australians from Arab and other immigrant and refugee backgrounds.

The volume contains two of Hage’s early books, White Nation (1998) and Against Paranoid Nationalism (2003), and some later essays exploring the place of racism in the rhetoric and practice of Australian multiculturalism. The foreword has been written by “critically conscious daughters and granddaughters of Lebanese, Palestinian and Egyptian immigrant and refugee settlers”, who acted as a reference group for the republishing project.

While the republished works were mainly written early in the second generation, their continuing relevance is both salutary and disturbing. The issues they raise remain deeply embedded today. Yet they also reveal how much has changed. There is a growing acceptance among “multicultural Australians” of the consciousness that Sweatshop advocates, and a moral rejection of much of the situation that Hage condemned.

Hage’s work began to take shape in reaction to the still-dominant Labor multiculturalism of the last years of prime minister Paul Keating. Hage argued that both Labor and the Coalition’s rhetoric and celebration of multiculturalism masked an ongoing reality of racial hierarchy and White privilege.

This privilege, Hage wrote, was bolstered by the capacity of official multiculturalism to authorise certain types of diversity, placing some within the boundaries of acceptability, while excluding others. Yet even behind that veneer there lies – or wriggles – another reality, where only White people are secure enough to unselfconsciously lay claim to the right to define the nation.

What is a White person?

Let’s begin with a critical question: what is a White person?

For Hage, it is a self-referential category into which White people put themselves. That is, people who think of themselves as White are White people.

It is not an ethnic label, in the anthropological sense that it has determinable mores, values and common histories that can be empirically discovered – though values and orientations are indicative. Nor is it racial, in the older sense of race as a bio-social category, with shared DNA clusters associated with territories of origin.

Rather, it is a “fantasy position” born out of colonial history, one that is essentially European. It is imagined to be rooted in the stories of north-western Europe: stories of empires won and an Enlightenment project sustained.

Reality, for a very disparate non-White world, is rather different.

Hage’s non-White world is focused on the Levant and its diasporas. It is important to understand the contradictions, for Hage, of being from Christian Lebanese stock (even without any theocratic perspective), yet oriented towards the metropolitan culture of Paris, where he studied under the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences.

Hage came of age within the Lebanese Civil War. Christian fascism and the Phalange, vied with trans-Arabism and an increasingly radicalised Islam. The European, anti-colonialist, democratic, non-sectarian left also sought to find a space. These contradictory and complicated intertwinings of love and hate have drawn Hage today to a focus on the struggle of Palestinians under the Israeli occupation.

Such different realities are Hage’s project. His lifetime has been committed to exploring, exposing and unravelling the dynamics through which different pictures of the world are formed in minds, cultures and social practices, and the way these pictures are contested, hidden, revealed and sometimes purged.

The underlying frameworks, shaped by class and culture, have been forged by imperial adventures and their often murderous consequences. While Hage writes about “race”, he reminds us this is not the “race” of the initial imperial invasions. It is race introduced from another place, then subjected to the tortuous compression of settlement and the normalisation of Otherness.

Hage warns us often that he recognises the power that sought to create the “Aboriginal race” in what became Australia. Though the reality of Indigenous oppression pervades his work, he does not address it directly. But he does suggest the power of the invaders has developed into a pervasive system of racialised control.

The power to set the agenda is the scaffolding that defines the struggles of the Australian nation. The everyday conceptions of who belongs, who can claim to say who can belong, and the consequences of these types of statements, set the conditions of possibility for the nation “going forward”.

“Race” lubricates this conceptual mechanism, making it move smoothly for some, while remaining slippery and dangerous for others.

Read more: Racism of rigid legalism greets asylum seekers and their kind

White Nation

In White Nation, Hage draws on two methods: one provided by his studies with Pierre Bourdieu in Paris, and another developed in the social anthropological space of ethnography and listening.

The Bourdieu dimension translates a Marxian view of class (as in, ruling class) into a less homogenised constellation of power. In this view, cultural capital draws together skills, knowledge, languages and even “looks” that enable the individuals who have them – and, importantly, share them with others – to replicate those forms, reinforcing their value and authority.

Among his many sources, Hage draws on letters to the editor, which provide a wealth of narratives to be unpicked. White people, suggests one letter, are more immediately seen as Australian (part of the dominant cultural group), even when they have only recently arrived. Others who have different “looks” – those who wear distinctive clothes, for example (the headscarf is a marker of difference) – aggravate. Racial and gender power is exerted through “tearing off the veil”.

Hage proposes that multicultural policies contain, at their heart, the logic that those who advocate and celebrate tolerance are capable of being, and perhaps have been, intolerant. “Mutual tolerance”, in other words, is only possible between parties who have the power to be intolerant of each other. The multicultural edifice thus depends on intolerance – an intolerance that is contained within boundaries of acceptability, but always pressing to escape.

In a racially demarcated social space, not everyone can be tolerant. The least powerful do not “tolerate” their racist harassers. They may avoid them, or be subjugated by them, or resist them, or seek to form an alternative ethnic will.

For Hage, the dark arc of refugee incarceration demonstrates the nature of this interaction, and how it is narrativised in the cause of creating a “good” multicultural nation. The nation’s tolerant multicultural goodness is constantly being challenged by “bad” ethnics: those people who seek refuge “illegally” in Australia, or contest the hegemony of Whiteness in other ways.

As Hage notes, White multiculturalism evades any commitment that “we are a multicultural community in all our diversity”. Rather, “we” only acknowledge our diversity when we can calculate a value that can be attached to that portion we select to notice.

Moreover, argues Hage, these views, be they for or against multiculturalism, all stand upon an edifice that assumes White superiority – and fantasises Australia as a place in which White superiority “should reign supreme”.

The politics of White decline

In the decades since White Nation first appeared, the politics of White decline have become an increasingly mainstream concern.

The current debate over legislation banning Nazi symbols, ASIO’s warnings about the apparent spread of White power groups and the devastation caused by online racism have positioned the White-decline narrative as a central threat to social order. This narrative played a key part in the anti-vaxx movement, despite the multicultural makeup of that movement.

Some of this was already emerging when Hage published Against Paranoid Nationalism in 2003. The primary focus of anti-migrant sentiment the 1990s had been on “Asians”, particularly Indo-Chinese refugees, and the emerging urban phenomenon of youth gangs and triads. The events of 2001 shifted this focus. A national paranoia erupted, generated locally by “Arab” drug lords and rape gangs, and globally by Islamist attacks on Western targets.

By the time of the invasion of Iraq by Western forces including Australia in 2003, Hage had two strong characters in public life who represented and intensified this paranoia: the then prime minister John Howard, victorious in 1996, and Pauline Hanson, who entered parliament that same year as a disendorsed Liberal Party candidate. Hanson alluded to their apparent political symbiosis when she spoke of the perception that racial tensions were being “inflamed by me and condoned by him”.

Both played a role in White Nation – but they foreground Against Paranoid Nationalism.

Worrying and caring

In Against Paranoid Nationalism, Hage proposes that two opposing stances – worrying and caring – establish the parameters of the narcissism and paranoia engulfing Australia.

Worrying about the nation’s present and future breeds an intense fear and hatred of outsiders who might threaten the interests of those who claim a unique right to worry. Colonial history, as a contest of explanatory and emotional narratives, becomes a struggle between conservative critics of “black-armband” perspectives on colonialism, and progressives searching for an alternative way of thinking through the possibility of an non-paranoid, inclusive identity.

The book, more of a compilation of linked essays, opens with an argument that neoliberal economic theory reshapes the social into a market, where individual interests emerge paramount and communal sense fragments and dissipates. What holds such a society together is the cultivation of images of threat.

Only strong and selfish stances are considered sensible and authorised by the state. It claims alone to stand against the threat from without – exemplified by asylum seekers and Islamist terrorists – and threats from within, from Indigenous challenges to the colonial project, and ethnic enclaves that emerge like cancers.

The state “worries” for the national project and those who support it. In the process, people become less willing to hope for a more caring future.

Against Paranoid Nationalism ends with a reference to what Hage calls the Black Economy – that is, an economy that depends on the theft of Aboriginal land. Even the “social gifts” that recognise the presence of individuals, and to some extent succour them, are a consequence of Australians being receivers of stolen goods.

Hage concludes that “our colonial theft […] will remain the ultimate source of our debilitating paranoia”, forcing us to worry and never really letting us care.

Against Paranoid Nationalism, together with the later essays collected in The Racial Politics of Multicultural Australia, offers a readable and challenging engagement with the issues that confront us today as a multicultural nation – one with a history of colonial invasion, but which is, by daring to hope, seeking not to have a racist future.

Hage has made a singularly powerful contribution to our understanding of Australian and global racism, and the politics of domination and resistance. He recently celebrated his mentor, Bourdieu, in a series of European lectures. Bourdieu, I am sure, would be proud of his student. We are all the better off for Hage’s eclectic, systematic, imaginative and penetrating assessment of the human condition in this time of late imperialism.

I have known Ghassan Hage since the early 1980s, when I first met him when I was director of the Centre for Multicultural Studies at the University of Wollongong. I interviewed him recently for a project on the "arc of the multicultural real". He has a more critical view of sociologists than do I. I am currently writing an Information Brief on Multicultural Policy past, present and future, for a community agency.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.