The German government will present its latest growth forecasts on Wednesday as Europe's crisis-hit top economy shows tentative signs it is finally turning a corner.

Improvements in key indicators, from industrial output to business activity, in recent months suggest that a hoped-for recovery may be slowly under way.

The German economy shrank slightly last year, hit by soaring inflation, a manufacturing slowdown and weakness in trading partners, and has acted as a major drag on the 20-nation eurozone.

Initial hopes for a strong rebound this year were dialled back as the economy languished, with Berlin in February slashing its growth forecast to just 0.2 percent. The International Monetary Fund followed suit last week and is now expecting the same figure.

But improving signs have fuelled hopes the lumbering economy -- while not about to break into a sprint -- may at least be getting back on its feet.

"The news flow is improving," said Berenberg bank economist Holger Schmieding. "The risks to our German call are tilting less to the downside than before."

He pointed to better readings in the closely watched Ifo index of business morale and improvements in manufacturing.

Last week the central bank, the Bundesbank, forecast the economy would expand slightly in the first quarter, dodging a recession, after earlier predicting a contraction.

And on Tuesday a survey showed that business activity in Germany had picked up.

The HCOB Flash Germany purchasing managers' index published by S&P Global registered a figure of 50.5 in April, up from 47.7 in March, returning to growth for the first time in 10 months.

Any reading above 50 indicates growth, while a figure below 50 shows contraction.

But slight improvements in indicators do not mean the government will make any big changes to its forecasts, with analysts still expecting tepid growth this year.

Already facing turbulence from pandemic-related supply chain woes, the German economy's problems deepened dramatically when Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022 and slashed supplies of gas to Europe.

This was a heavy blow for the country's manufacturers -- which still play a central role in the German economy, unlike in many other developed economies -- which had come to rely on cheap Russian energy.

While the energy shock has faded, continued weakness in key trading partners such as China has prolonged the pain.

Strikes in many sectors this year as workers pushed for better pay to combat inflation acted as a drag, as did higher interest rates as the European Central Bank has sought to tame runaway prices.

Higher wages and other costs have also prompted some major companies to scale down production in Germany, fuelling fears of layoffs and manufacturing moving abroad.

More long-term issues, such as an ageing population and a shortage of skilled labour, are also headaches for policymakers.

Business groups complain they face hurdles in improving their prospects, from red tape to a failure to enact much-need reforms.

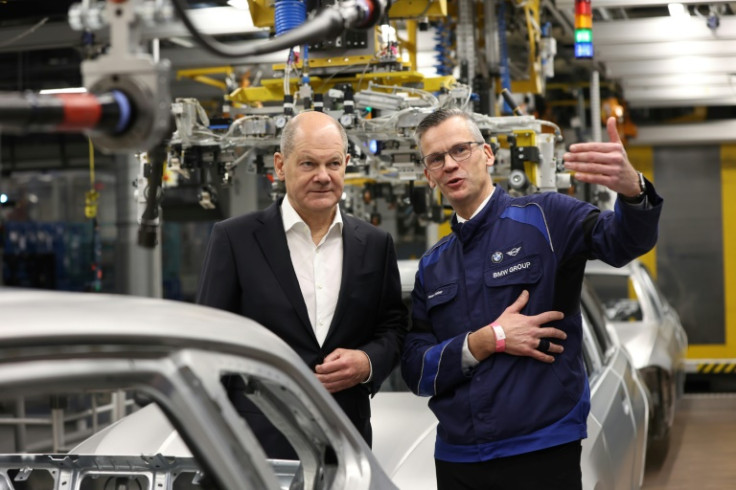

Disagreements in Chancellor Olaf Scholz's three-party ruling coalition are also hindering efforts to reignite growth, and bolster the greener industries of the future, critics say.

This week the pro-business FDP party, a coalition partner, faced an angry backlash from Scholz's SPD when it presented a 12-point plan for an "economic turnaround", which included deep cuts to state benefits.

While the economy's prospects may be starting to improve, a bumpy path ahead is still seen by some.

A "far-reaching recovery is not yet assured", said the Bundesbank in its latest monthly report.