Charles Mingus wrote the poignant ballad Goodbye Pork Pie Hat, which first appeared on his epic 1959 album Mingus Ah Um, in tribute to his gravely ill friend, saxophone giant Lester Young.

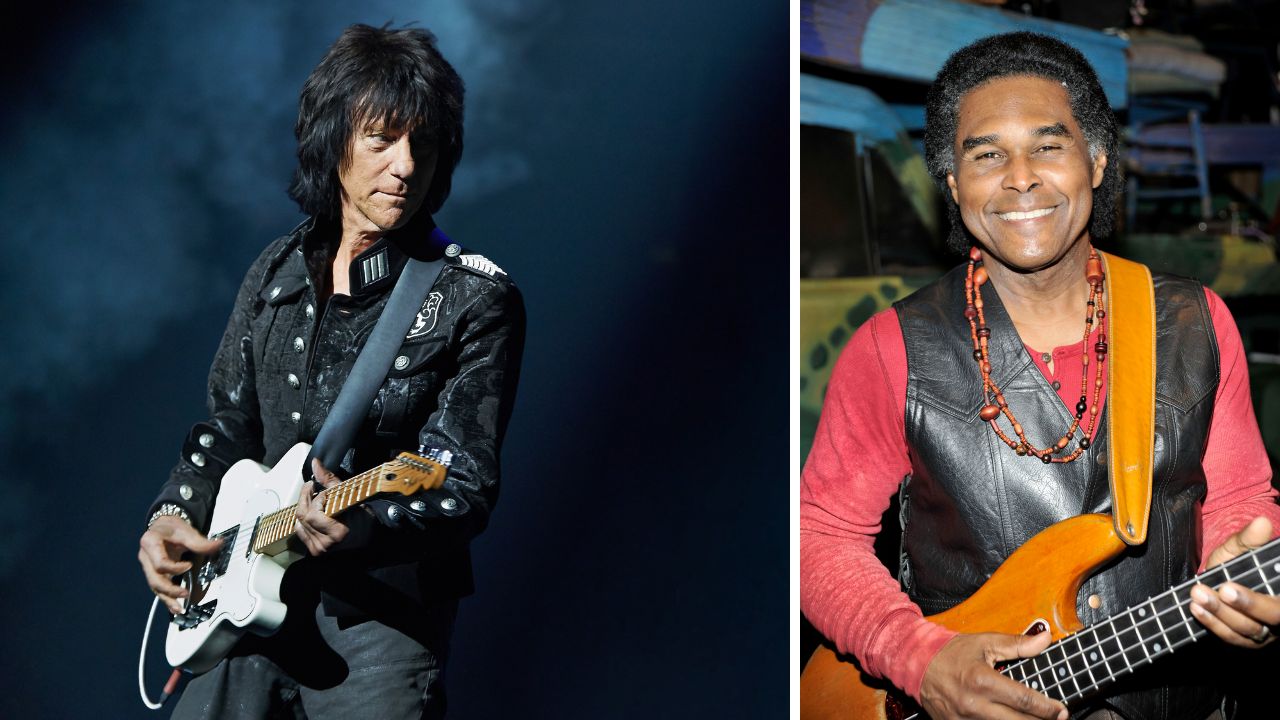

Since the original rendition, the song has gathered a bass guitar legacy, with covers by Stanley Clarke, Marcus Miller, and others, but it was Jeff Beck's take on the tune, on his 1976 classic album Wired, that brought the most success.

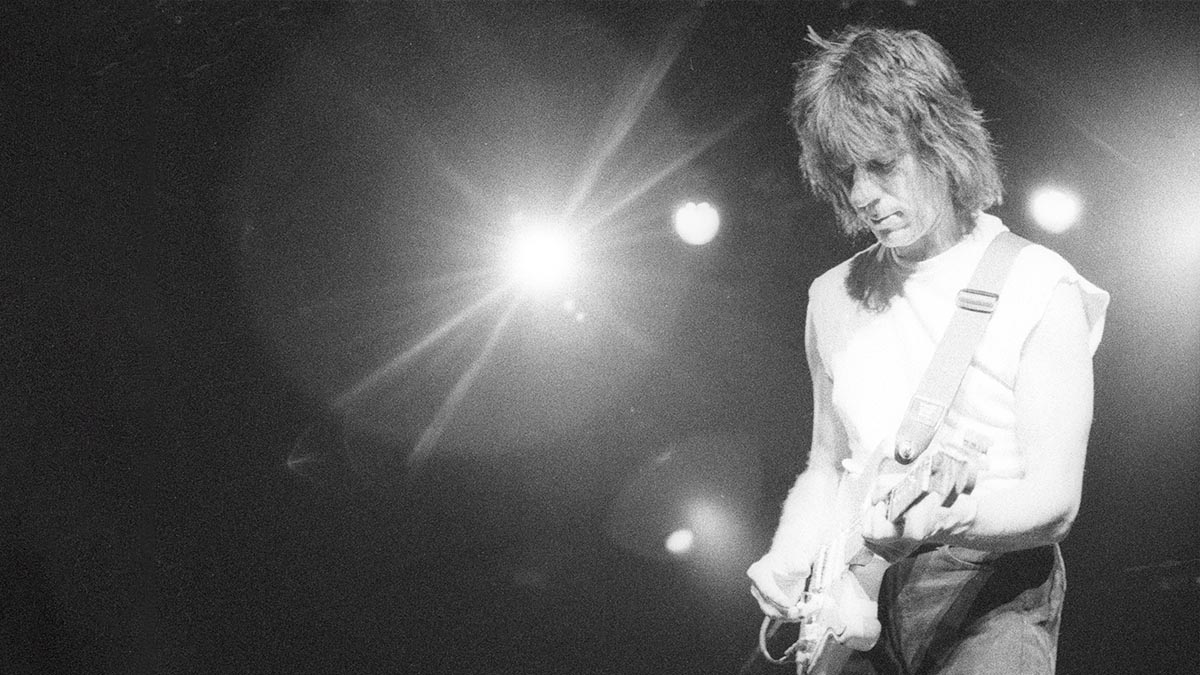

Wired, and its 1975 predecessor Blow by Blow, stand as milestones in Beck's career. Critics have hailed them both as pinnacle examples of instrumental rock, as well as some of the finest music made during the fertile fusion era.

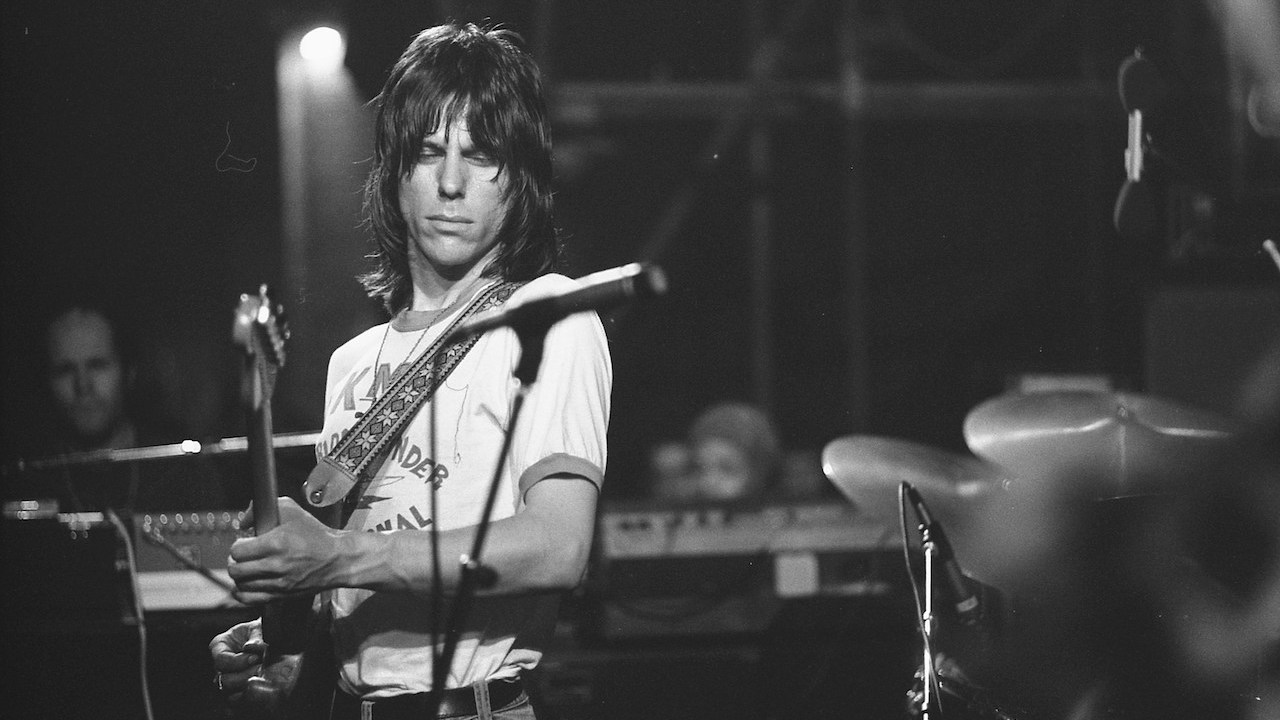

Following the recording of Blow by Blow (with Phil Chen handling the bulk of bass duties), Beck told his keyboardist, Max Middleton, he wanted to get “that funky drummer from America” for a world tour. Beck was referring to session legend Bernard Purdie, who, upon accepting the gig, was asked about a bassist.

“I've got a young guy who will be perfect,” Purdie replied. That “bloke,” as Beck would say, was 24-year-old Manhattan native Wilbur Bascomb Jr., son of noted Duke Ellington trumpeter Wilbur “Dud” Bascomb.

In February 1975, Bascomb and Purdie headed to Beck's castle in England to rehearse for the tour, which would find them splitting the bill with the Mahavishnu Orchestra. By the end of a very successful run that October, Beck – known for his abrupt shifts of interest – had become enamoured of Mahavishnu drummer Narada Michael Walden's playing and dissolved his quartet.

Bascomb received a call in November to head back to England to record Wired, with Walden, Middleton, and synth player Jan Hammer. The George Martin-produced album included Middleton's 5/4 classic Led Boots, and Bascomb's funky ostinato on Walden's Come Dancing.

Toward the end of recording, it was decided that a few more tunes were needed. With Hammer and Walden having departed, a teenage Richard Bailey (who had also appeared on Blow by Blow) came in to play drums. Bascomb contributed the meter-shifting Head for Backstage Pass, and Middleton delivered a reggae-ish ballad (recorded but not released) and got the idea to cover Pork Pie Hat.

In preparation for cutting Pork Pie Hat, Middleton taught Jeff Beck the melody, showed Bascomb the chords changes (no chart or lead sheet was used), and gave Bascomb and Bailey his idea for a groove – a medium 12/8 shuffle. He also suggested that Beck solo over vamps, instead of Mingus's complicated changes, and he dropped the original key of F down to D.

Returning to George Martin's Air Studios, Beck began having problems with the sound, leading him to eventually flee down the road – sans a frustrated Martin – to record the tracks at Trident Studios.

The quartet recorded live, with Bascomb plucking his '66 P-Bass (with an added Bartolini J-Bass bridge pickup). He went both direct and through an unknown miked amp at the studio. Bascomb made no fixes and only one punch: the final note, for which he got the idea to de-tune his E string and drop in a low D.

The track begins with a rubato run through the head, featuring Beck playing the melody. The tempo kicks in at bar 13. Bascomb enters and introduces some pentatonic fills, a signature move that became a key element of the piece.

“My active bass part was the result of several factors,” he told Bass Player. “First, we had no producer, because George Martin wasn't going to leave his own studio, so there was nobody telling us what to do or not do. Second, the tempo and the long vamps on one chord lent themselves to more bass movement.

“And finally, the nature of the band sort of indicated that I should step forward and fill up some space: Max always played sparsely and just right, Richard had more of a top-of-the-kit, lighter touch, and there was no second guitarist playing rhythm behind Jeff.”

For the start of Beck's solo and the first vamp in D, Bascomb continues his pentatonic ways, with fills at the back side of the bars. He then employs a jazz device that hints at upcoming chord changes by filling with notes from the next chord (here, the Bb and B leading to the C). Bascomb then uses octaves to get back to the original D tonality.

With a Bb vamp looming, he once again provides a precursor harmonically, via the Bb triad drop, and stays consistent with pentatonic fills, revealing his preference for reaching up to a high, bluesy, flat 3rd. Meanwhile, the influence of his pentatonic presence on Beck’s solo can be heard, where the guitarist unleashes a long, ascending pattern.

“I suppose there was a certain call and response aspect. It wasn't like I was trading lead riffs with Jeff – we were just reacting to his playing – but within that dialogue he was reacting to us, as well. Jeff was very loose; he never gave directions or said much. We were free to complement him how we saw fit.”

Following two more bars of D vamp, the song's head returns, with Beck restating the melody. Now dealt some hefty, angular jazz changes, Bascomb really rolls up his sleeves. He adds 10ths leading into the Ab maj7b5, and he slides up dramatically to outline the D11-to-D9 motion at the end of bar 42 (dig that doghouse-like, four-string drop on the last three beats).

“Almost everything I play on the electric I brought over from the upright – especially from listening to Sam Jones with Cannonball Adderly; Sam had all kinds of cool but subtle moves.”

Bar 45 contains another ear-grabbing upper-register chord outline, while the end of bar 47 boasts a killer upright-derived descending fill that runs pretty much the entire range of the instrument. Bascomb adds both a trill and a 5th-fret harmonic, and closes the tune with his punched low D.