The newly formed United Nations passed its first international treaty on Dec. 9, 1948, just three years after the Holocaust ended. The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was designed to prevent genocide from ever happening again.

But governments worldwide currently remain far from the goal of preventing genocide – despite 152 of them eventually signing on to the Genocide Convention.

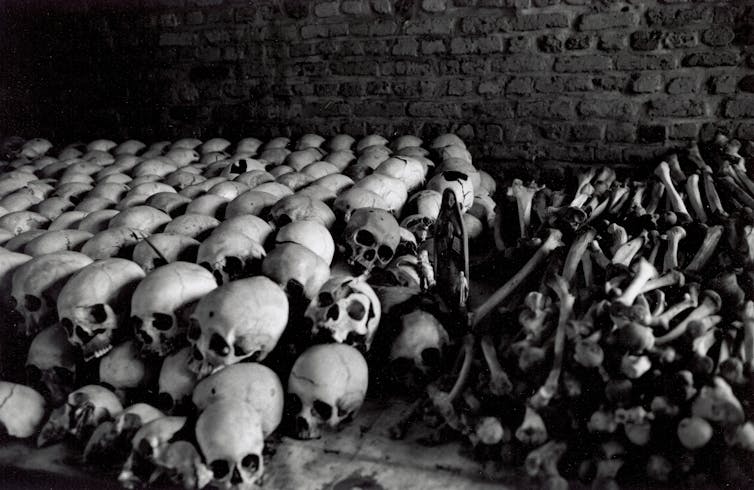

Genocide, meaning actions taken with the intent to destroy a group of people because of their identity, happened again in Cambodia in the 1970s. The communist Khmer Rouge regime tried to kill all ethnic Vietnamese and Cham people in the country, resulting in the deaths of 1.5 million to 3 million people. And it happened in 1994 in Rwanda, when the Hutu ethnic group murdered hundreds of thousands of Tutsis.

Today, governments are also carrying out genocide against ethnic minorities in Myanmar, where the military is killing the Muslim Rohingya people. Many experts and some governments, including the United States, also say genocide is happening in China, where the national government is arbitrarily detaining Uyghur people.

Some human rights experts also say that there is growing evidence Russia is committing genocide against the Ukrainian people.

Genocide has not been prevented, almost 75 years after the Genocide Convention was passed, in part because of a misunderstanding about how genocide happens and what prevention looks like.

As co-director of Binghamton University’s Institute for Genocide and Mass Atrocity Prevention and a program director at the Auschwitz Institute for the Prevention of Genocide and Mass Atrocities, I focus on helping students and government officials understand five important things that scholars and practitioners have learned about preventing genocide. Here are those five key points.

Genocide is a process, not an event

Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin first coined the term genocide in 1944. Specifically, the Genocide Convention protects racial, ethnic, religious and national identities.

Although this destruction often happens through mass murder, it can take other forms. It can mean taking children of one group away from their parents and transferring them to another group, for example.

Genocides are not events that happen overnight. They are long-term social and political processes that begin long before mass killing.

For instance, the Nazis did not build death camps immediately when Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany in 1933. The Holocaust began with smaller steps, like preventing Jewish people from holding certain jobs, then preventing Jews and non-Jews from marrying each other.

It was not until the late-1930s that the Nazis transitioned to their Final Solution, which called for the destruction of all Jewish people. And the Nazis did not construct the first death camps until 1941. But all these steps over the years constituted what we now call the Holocaust.

Prevention is also a process

When people understand genocide as a process and learn to recognize the early stages that can lead to genocide, there is more opportunity to intervene before people are killed.

Prevention scholars and activists stress a long-term view of prevention that entails three stages.

First, there are actions people can take before genocide occurs to make sure it never happens. This involves identifying which groups of people are at risk of violence, then passing laws, for example, to protect those groups.

A second stage of prevention involves responses to a genocide once it breaks out. This can include using military troops to quash violence. But it could also extend to things like diplomacy, threats of prosecution and economic sanctions.

Finally, a third stage of prevention only occurs when a genocide has already happened. This stage aims to prevent its recurrence. This can include things like truth commissions, which aim to expose and document mass violence or other periods of turmoil, trials against the perpetrators or reparations to victims.

Obviously, stopping a genocide before it actually happens is the most effective and least costly form of prevention.

Prevention starts with reducing risk

Scholars have identified certain risk factors that make a society more likely to experience genocide. Countries with poor human rights records, for example, are typically at higher risk of genocide.

Poor economic conditions and a country’s history of conflict are also factors that could contribute to large-scale violence against a group of people.

Migrants and refugees are people who are especially at risk of experiencing identity-based violence.

When more than 1 million Venezuelan refugees entered Colombia starting in 2015, for example, many risk factors were present. One risk factor is when a group has unequal access to basic resources and services.

The Colombian government saw this as a risk factor and responded. It introduced a new policy in February 2021 that gave temporary legal status to all refugees. This gave them access to public services, education and health care, immediately lowering the risk for large-scale violence in Colombia.

True prevention starts at home

Every country in the world features some risk factors associated with genocide, including the United States.

But not every country in the world has the same level of risk.

In recent years, many countries have recognized the need to assess their own genocide risk factors. Some have fashioned specific government initiatives focused on genocide prevention. This work spans government departments and ministries to make sure governments keep genocide prevention in focus. Argentina, Mexico, Tanzania and Uganda are among the countries to undertake this kind of work.

The United States also has a national strategy focused on genocide prevention, though it does not look inward at this point – it is only concerned with atrocity prevention in other countries.

There are also several nongovernmental organizations that assist governments in prevention work, including the institute where I work.

Prevention isn’t over when the genocide stops

There could be temptation to think that when mass killing stops, the work of prevention is finished. But one of the biggest genocide risk factors is if a society has already been involved with one. For example, the Holocaust happened only a couple decades after Germany perpetrated the genocide of Herero and Nama people in present-day Namibia.

For this reason, the work of prevention continues, even after a genocide is over.

This requires societies to deal with the risk factors that allowed genocide to take place, even as they rebuild.

For instance, after the 2007 elections in Kenya, massive inter-ethnic electoral violence broke out, killing over 1,000 people and displacing at least 350,000. The United Nations and the Kenyan government collaborated with nonprofits and local leaders to develop an early-warning network called the Uwiano Platform for Peace. This provides a hotline system where ordinary citizens can call or text if they hear hate speech or see violent acts. The information is then verified and, if it is credible, the central platform contacts local authorities to respond.

Following the implementation of Uwiano, no large-scale violence was reported after the 2010 and 2013 elections. Of course, Uwiano was not the only reason that Kenya avoided this violence. It took many international, national and local experts and others working together.

There is no single way to prevent genocide. What is clear, however, is that there are many different measures available that, together, can reduce the risk of genocide.

Kerry Whigham is affiliated with the Auschwitz Insitute for the Prevention of Genocide and Mass Atrocities, an international non-governmental organization.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.