As the war between Israel and Hamas has intensified in Gaza, disinformation and conspiracy theories about the conflict have been increasingly circulating on social media.

At least that’s what I found in my analysis of some 12,000 comments posted on Telegram channels in the immediate aftermath of Hamas’ October 7 attack on Israel. Not surprisingly, I also found language about the war was more likely to be threatening or hateful than language used in comments about other topics.

Many comments on Telegram also linked the Israel-Hamas conflict to dangerous, antisemitic conspiracy theories related to the war between Russia and Ukraine, hundreds of kilometres away on another continent.

For instance, I found the Russian invasion of Ukraine was characterised by these conspiracy theorists as a justified resistance against the “Khazarian Mafia” (so-called “fake Jews”) who supposedly govern Ukraine either as Nazis, or like them.

Commenters on Telegram characterised Hamas’ October 7 attack in similar terms – as an attack against “fake Zionist Ashkenazi Jews” and Nazis.

Both conflicts were also characterised as “new world order” plots. Proponents of these conspiracies believe that powerful elites (often characterised as Jewish) are secretly trying to establish a totalitarian world government or other forms of global oppression.

A comment in one of the channels summarised this view, arguing “these globalists are evil starting a second psyop [psychological operation] front after Ukraine failed”.

Other comments linked the two conflicts by calling Western supporters of Ukraine hypocrites for condemning the actions of Hamas. As one user argued: “The West’s weapons in Ukraine [were] sent to Hamas for the offensive.”

Polycrises and conspiracies

Many of these conspiracies are not new on their own. However, what is unique in this situation is the way people have linked two largely unrelated conflicts through conspiracy theories.

Research has shown that overlapping crises (often referred to as “polycrises”) may accelerate the spread of conspiracies, possibly due to the psychological toll that constantly adapting to rapid change places on people.

When crises overlap, such as wars and global pandemics, it can amplify the effects of conspiracies, too. For example, the amount of prejudice and radicalisation seen online may increase. In extreme cases, individuals may also act on their beliefs.

Although these conspiracies are appearing on the fringes of social media, it’s still important to understand how this type of rhetoric can evolve and how it can be harmful if it seeps into mainstream media or politics.

How I conducted my research

I have been following several public Australian Telegram channels as part of a broader project investigating the intersection of conspiracy theories and security.

For the latest phase of this research, which has yet to be peer reviewed, I analysed 12,000 comments posted to three of these channels between October 8 and October 11.

To analyse so many messages, I used a topic modelling approach. This is a statistical model that can identify frequently occurring themes (or topics) within large amounts of text-based data. Essentially, topic modelling is similar to highlighting sections of a book containing related themes.

There are many approaches to topic modelling. I used BERTopic, which generates topics by “clustering” messages with similar characteristics, like words, sentences and other bits of context. In total, I identified 40 distinct topics in the comments I analysed.

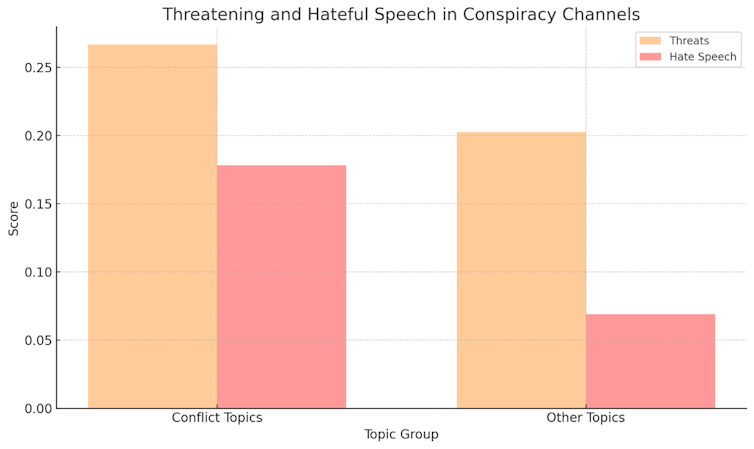

I then split these topics into conflict and non-conflict groupings to analyse the sentiment behind them. I used Google’s Perspective API algorithm to do this, as it can score text on a scale of zero to one for hateful or threatening language. The results show that conflict topics were more likely to involve threatening and hateful speech.

A key reason for this is the antisemitic nature of the most common conflict topic grouping (key words: “Israel”, “Jew”, “Hamas”, “Zionist”, “Palestinian”). One representative comment from this group, for instance, called for the elimination of Israel as a state.

I found Islamophobic messages in this topic grouping, as well. For example, some comments suggested Hamas’ actions were reflective of Islamic beliefs or demonstrated the danger posed by Muslims more generally.

The second-largest topic (key words: “Ukraine”, “Russia”, “Putin”, “war”, “Islam”, “propaganda”) captured discussions linking the Hamas attacks to the Russia-Ukraine war. Messages did this by casting both conflicts as justified on similar grounds (a fight against alleged Nazis and Zionists), or by linking them to global conspiracies.

And I found variations of the “new world order” global conspiracy theory in other topics. For instance, the fourth-largest topic (key words: “video”, “clown”, “fake”, “movie”, “staged”) included comments accusing Israel and other common conspiracy figures of staging the Hamas attacks.

This closely aligns with topics about the Russia-Ukraine war from my broader project. One of the most frequently discussed topics (key words: “Putin”, “war”, “Nazi”, “Ukraine”, “Jewish”) frames Ukraine’s defensive efforts as a sinister conspiracy, usually involving Jewish figures like Ukraine’s president.

Read more: Israel-Gaza conflict: when social media fakes are rampant, news verification is vital

How to combat the spread of conspiracy theories

As noted, the conspiracy-friendly nature of social media, in addition to overlapping “polycrises”, may increase people’s levels of prejudice and radicalisation.

Australian security agencies have already warned about this risk in the ongoing Israel-Hamas war. ASIO Director-General Mike Burgess warned of “spontaneous violence” arising from “language that inflames tension[s]”.

Read more: Far-right groups move to messaging apps as tech companies crack down on extremist social media

Research has also shown a strong relationship between conspiracies and antisemitism, which presents clear risks for Jewish people. Indeed, antisemitism reached unprecedented levels in the United States in 2021 and 2022, possibly due to the series of overlapping crises the world was experiencing at the time.

Countering online conspiracy theories is therefore an important, but challenging task. Effective counter-strategies involve a mix of preventative and responsive approaches targeting both the suppliers and consumers of conspiracies.

This includes increasing our investment in education, reducing social inequality, and carefully debunking conspiracy theories when they appear. Awareness of the dynamics and spread of conspiracy narratives is a necessary first step.

Nicholas Evans is affiliated with the Tasmanian Institute of Law Enforcement Studies (TILES).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.