Classic interview: We go back in time to just before the release of 1995’s Blues For Greeny album, Gary Moore reflected on the influence and friendship of Peter Green to Guitarist magazine's David Mead, and the Bluesbreaker’s legacy…

Gary Moore officially hung up the spandex and turned his back to the music that he grew up listening to around about five years ago. The blues was a formative influence upon his playing, but often such a dramatic mid-career change of tack has unfortunate results, and for many only the creative doldrums are all that awaits.

Happily, in Gary’s case this proves not to be the case. His first pure blues outing, the aptly titled Still Got The Blues, created an entirely new momentum for the Northern Irish guitarist, which has spurred him on to release two further blue hued projects since – After Hours and Blues Alive.

The latest venture is called Blues For Greeny, an album dedicated entirely to the music of Peter Green. Unable to contain himself any longer he invited Guitarist along to the studios for a sneak preview.

“Basically it’s just that,” he enthuses. “An album of Peter Green’s music, although it concentrates more on the blues aspect as opposed to his more poppy things. I’ve ignored the obvious things like Albatross and Man Of The World – in fact the only single of his I’ve done is Need Your Love So Bad, which I’ve been playing for a long time and so it means a lot to me. It’s a great song and I love Peter’s version of it but I’ve taken the guitar solo on a lot further at the end.

"The original is much shorter than people realise actually; as soon as the guitar comes in at the end it’s gone.”

While at the studio Gary previews several tracks from the album for us: Long Grey Mare, Merry-Go-Round, If You Be My Baby and I Loved Another Woman…

“Apart from those, there’s things like The Same Way from A Hard Road, which was either the first or one of the first vocals Peter ever did. I’ve tried to go from John Mayall onwards through Fleetwood Mac up to when he left.”

So there is a strong chronological aspect to the album?

“Yeah, but it’s not put together in that way. The songs are compiled as they fit together as opposed to chronologically. There are a couple of more obscure songs that I’ve chosen from the Fleetwood Mac period, things like Love That Burns and If You Be My Baby, which is more the rough and ready side of Peter’s music.”

It was like going back to the old roots again because I felt that in a blues sense I’d drifted away very much from the essence of what I started to do when I did Still Got The Blues

The end results speak for themselves, but what was it that initiated the project in the first place?

“I don’t really know to be honest! I’ve wanted to do it for a long time and I just felt that now was a good time. It was like going back to the old roots again because I felt that in a blues sense I’d drifted away very much from the essence of what I started to do when I did Still Got The Blues.

"When I did that album I started off doing stuff more like this – it was more contained, much more low key with just a bass player and drummer. But by the time the album came out and we went on the road, the whole thing had got bigger and bigger and it became like a rock thing again.

"The whole thing got blown out of proportion and I ended up playing very loud with a big distorted guitar sound and I lost the essence of it. It was very successful and everything, but that’s not the point. The point is that musically this is more where it started off, so I’ve gone right back to that very bare feeling. Merry-Go-Round is just done with bass and drums; it’s very dry and very pure.

"It’s got that essence of what Peter was about, which was that very stripped down, minimal way of playing and that was something I hadn’t done a lot of on record before but something that I really enjoy listening to.”

Despite its influences you don’t feel ‘tribute’ is an appropriate description?

“I don’t really like to use that word because the guy’s alive – Peter Green’s not dead. People may say it’s a tribute album but for me it’s a thank you album – it’s dedicated to Peter, it’s his music, but it’s more an appreciation, me saying thank you to him for everything that he’s given to me, both musically and personally.

"In the early days I got to know him quite well because when I was in Skid Row, we opened for Fleetwood Mac and Peter helped me a lot. He helped us get management sorted out and a lot of what has happened to me is through meeting him, so this is by way of a thank you.

This is the first blues album I’ve ever recorded, to be honest because although Still Got The Blues was very blues influenced, this is much more a pure blues record for me

“This is the first blues album I’ve ever recorded, to be honest because although Still Got The Blues was very blues influenced, this is much more a pure blues record for me. There’s a lot less of the more aggressive, busy sort of playing on the record. It’s a more straightforward, clean sound much of the time.

Did you consciously try to emulate Peter’s guitar sound on the album?

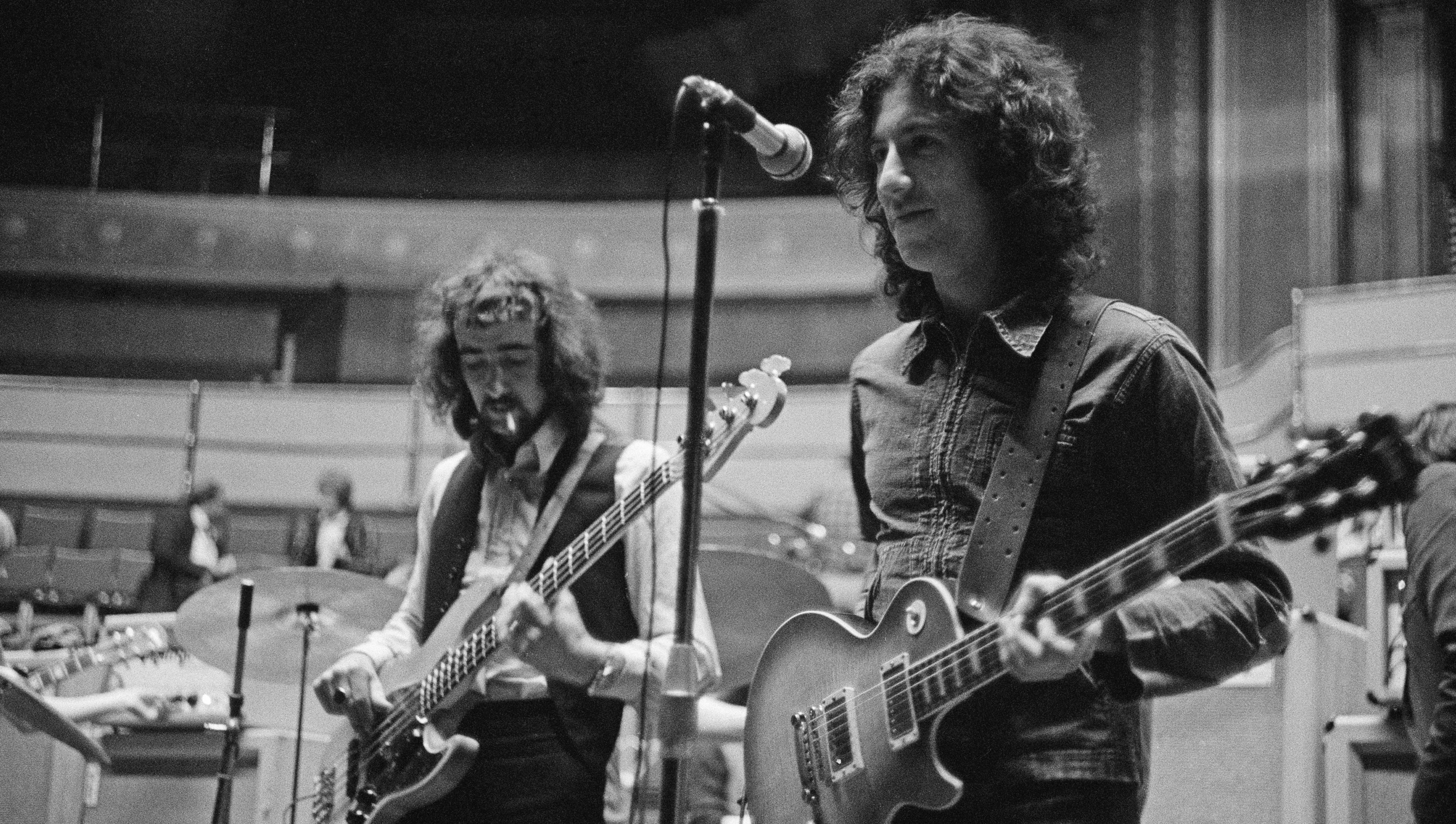

“Well I used his guitar! When you pick up that guitar it’s kind of hard to play any other way, and so of course I wanted to play along those lines. But I also wanted to come through myself, which I think I’ve done – it’s just obtaining a balance between those two things.

"Obviously I don’t play the same way as Peter, but I could do a passable imitation of Peter Green; if you gave me a guitar I could sit here and probably get closer than anybody else.

"But there’s no point in coming across like an expensive bar band, you want to let whatever it is you do come through in the music. So I didn’t just want to clone it and do everything exactly the same as he did, I’ve tried to be faithful to the original songs but put a bit of myself in there as well.

“Definitely the vocals are quite different and I think that’s something that will set it apart. There are places where it is very close to the original in terms of the sound and everything, like I think Love That Burns is close, we’ve used the same horn line and everything.

"There’s something about it, the sound became very similar to the old version. There was a sort of nasal sound to the whole track and the way the guitar sounded like it was bleeding down the vocal mic which brought out all the mid-range. So there’s a lot of that on that particular track, and that’s probably the closest I get to the way he plays on the record.”

"This is the livest studio record I’ve ever made"

Was there any attempt to recreate the feel of a 60s recording in the studio by having all instruments playing together live?

“We all played live but I played in the control room a lot of the time because I don’t like wearing headphones. But we still played all together and we could see each other so it was just like me being in a booth, all screened off, except I had the luxury of being able to hear everything coming through the speakers.

"This is the livest studio record I’ve ever made, actually, even some of the vocals are live. Equipment-wise I used a little Fender Vibroverb reissue, a Matchless amplifier and a 60s Fender Bassman. A lot of the time we were going through a 4x12 Marshall cabinet. The key elements in recreating Peter’s sound are basically that guitar and the touch, really.

"You can’t recreate his sound to the point where it’s the same, you can only approximate it – but luckily I’ve got the guitar. I mean, everyone knows that one of the pickups is turned round the wrong way but I’ve played other guitars where people have done that and it doesn’t sound anything like it!

"There’s still something else about that particular guitar, it has a characteristic sound so there’s that and there’s the point of not overdriving it too much, obviously.

"Peter always had a clean sound and I think it’s down to the playing after that; it’s down to the touch and sensitivity of the player, and the phrasing and the he space that you leave. It’s all those things.”

Some of your playing on the album is very intimate, suggesting the guitar’s volume control was rolled right back…

“Well, when I’m playing I fiddle with the sound a lot, changing the tone, so at times the guitar would get full, at other times I’d back it off. It’s just depending on how I feel at the time really.

"Merry-Go-Round is very close to Peter’s old sound I would say. It was on the first Fleetwood Mac album, the second or third track on there and it comes in and it’s very dry. It’s like, wow, I don’t think I’d heard anything that pure before, it was so basic, just with the bass and drums behind it.

"So the guitar was very in your face – very present with no echo or anything like that.”

How did you come to meet Peter?

“I’d seen him play with John Mayall just after Eric [Clapton] had left the band when I was 14. He had a Selmer amplifier, which was rented because no one could afford to bring their own gear and he had to play All Your Love. I thought it was going to sound like shit but the moment that he plugged in he went into that lick at the start and I remember the whole room was vibrating!

"It was an amazing experience just to hear a guitarist walk on stage and plug into this amplifier, which I thought was a pile of shit, and get this incredible sound. I’d never heard anything like it and I thought, God, if I could ever get a guitar to sound like that or even better, to have that guitar!

We both sat there and talked all night and played together, no amps or anything – there weren’t any practice amps in those days

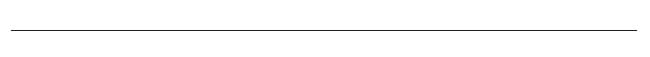

"He was absolutely fantastic, everything about him was so graceful. Anyway, later on when Skid Row opened for Fleetwood Mac at the National Stadium in Dublin around 1969 or 1970, I was only 16 or 17 at the time and Peter had said to this DJ guy who was hosting the show that he’d like to meet me.

"I was really thrilled, because Peter was one of my big heroes and so I just went up and said hello and he said, ‘Oh I really like your playing, do you want to come back to the hotel afterwards and we’ll have a chat?’ I had to go and play another gig after that but he waited for me back at the hotel and I went up to the room and there was Mick Fleetwood and Peter sharing a room and he had the guitars on the bed.

"We both sat there and talked all night and played together, no amps or anything – there weren’t any practice amps in those days so we just played and talked all night. It was great. Then I travelled with him to the next gig and he persuaded his manager to bring Skid Row over to England and then we stayed in touch after that for quite a while.

"I used to go up to his house and stuff and hang out there and play with him sometimes. I haven’t seen him for quite a few years. I saw him a couple of times when I was recording Back On The Streets in the late 70s. He was downstairs in the bar at the studio and I said, 'Come up, I want to play you this track.' We’d done this slow version of Don’t Believe A Word, which was very much in the Fleetwood Mac style.

The [Greeny] Les Paul was leaning against the chair in the studio and he came in, walked across and brushed it with his hand – that’s why it’s given me another 20 years of magic ever since!

"The [Greeny] Les Paul was leaning against the chair in the studio and he came in, walked across and brushed it with his hand – that’s why it’s given me another 20 years of magic ever since! It was losing the old vibes having been in my hands for a while, so he put some of the old magic back into it for me and then he came up the stairs and sat in the control room and we played him Don’t Believe A Word and he said, ‘That’s like something Fleetwood Mac would have done…’ and we went, ‘Er, really?’”

Peter Green has carved his own enigmatic niche in rock history – similar, perhaps, to Syd Barrett…

“In so much as no one knows much about him any more – yeah, he’s a bit of a recluse for whatever reasons. I personally think that you just have to listen to the way Peter played, you just can’t play like that and not be incredibly spiritual and sensitive and this business is not the place for that kind of person.

He said this himself – he said he wasn’t cut out for the music business and I think he did the right thing leaving. I wish he would come back and play and I wish he was playing today and I wish he’d been playing all through those years. But because of the way it affected him it just definitely wasn’t the right place for him to be. He was an amazingly deep person – I mean, it’s in the music isn’t it? Anyone can hear that.”

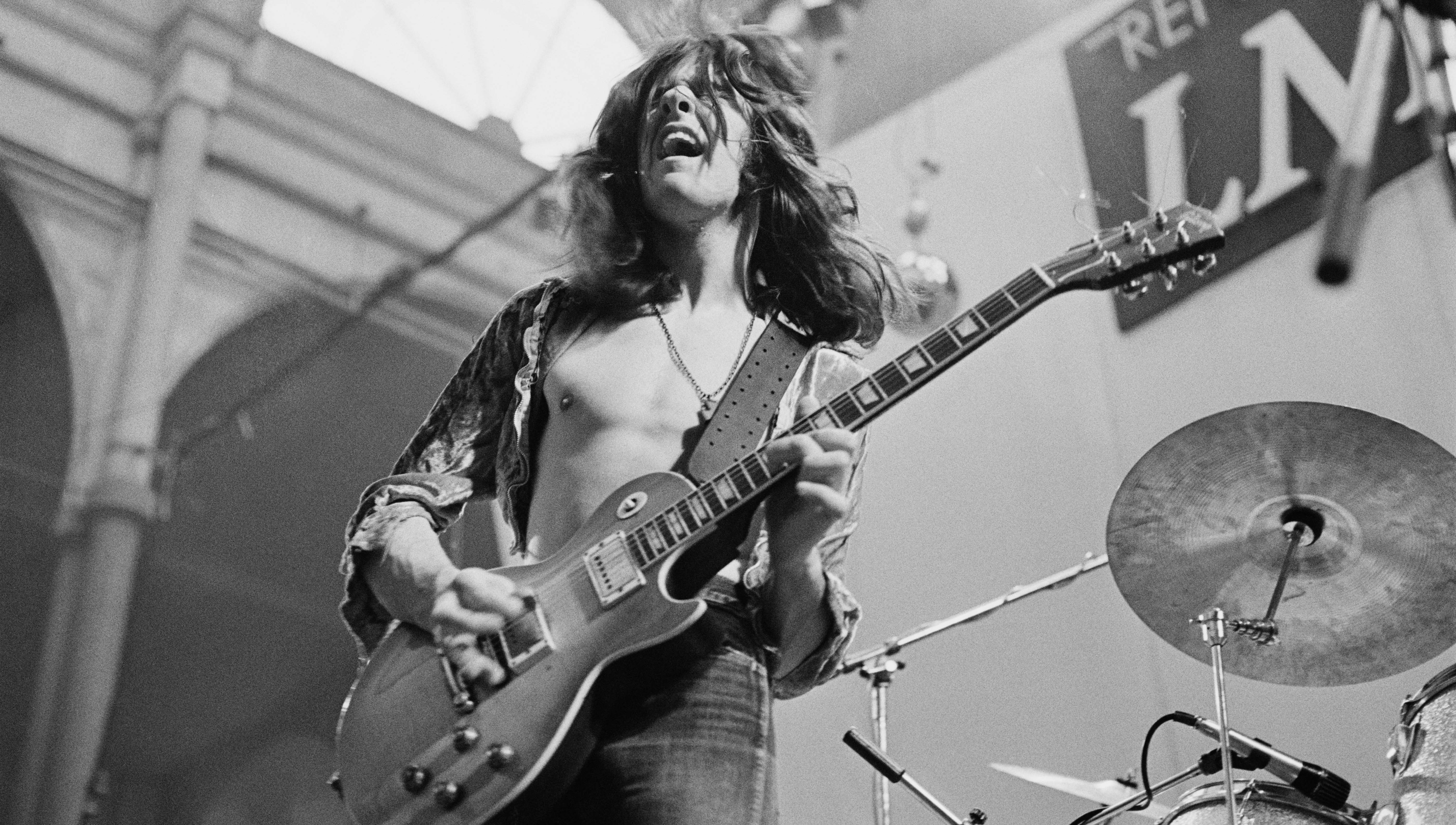

One of your lasting memories of Peter was a nightmare gig at London’s Roundhouse venue…

“I’d met him the night before, and he asked me to play with him. So I was struggling to get to the Roundhouse on the tube all the way across town from the East End. I ran up to the door, Les Paul under my arm, and said, My name’s on the guest list, I’m playing with Peter Green.

"The guy on the door told me that Peter was already on stage so I had to run round to the back of the stage, get my guitar out, plug into this horrible amplifier with a dodgy lead, which was just buzzing the whole time and get up and play. He just sort of looked at me like, You’re late!

But I think that was his last major gig. It was such a bring-down for me because I’d always wanted to play with him properly and I’d played with him in a room before and it was great and then I had to plug into this horrible amp and he had his Fender there, a little Twin, and he had this beautiful sound. I sounded like a joke but that’s one of the lessons you have to learn.”

Are there going to be any live dates to support the new album?

“I’m not going to tour with it but we might do a couple of things here and there or maybe some festivals in the summer but I’m not going to do a full blown concert tour with it, no.”

Is that decision based upon the intimacy of the music and the fear that it may not weather well at larger venues?

“I don’t know. I think on the surface it is but I think this stuff can work anywhere because the music is so powerful and soulful. I mean, if you go to a rock gig and someone plays a ballad it can still really come across, even though there’s a hundred thousand people there.”

One tends to associate Peter’s music – and perhaps blues in general – with the small clubs…

“Yeah, very much so. But I’m not crazy about playing in clubs anyway. I always think it would be great to play clubs again and then when I do I don’t like it because I just feel sometimes it’s a bit too intimate.

"I mean, we did a club, the Marquee, with BBM and the band nearly broke up! The volume was terrible and it was awful, a nightmare. It was the first gig we’d done together and we were under a lot of pressure.

"But the monitor desk was down on the floor with the crowd - we couldn’t even have it up on stage. All the luxuries you get used to – you come from rehearsing in the Academy in Brixton and you play the Marquee! It’s kind of round the wrong way isn’t it?”

On the subject of BBM (Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, Gary Moore), so many stories surrounded the band…

“Yeah, like they couldn’t get Eric so they got me! [laughs] It was so misunderstood! It happened so naturally and because of the people involved, it was perceived to be such a hype and it wasn’t at all.

"I would never ever get involved in anything that was a hype. It came about when I did a gig with Jack Bruce in Germany because his guitarist left very suddenly and he called me up and said he’d got to do this gig would I come out and do it? We had such a good time that I asked him to get involved in my next solo album. Jack came over and we wrote some things together.

Gary Husband from Level 42 was meant to be playing drums but he couldn’t make the sessions and Jack, amazingly, suggested Ginger to come and do it. At that point it was still a Gary Moore album.

"I was delighted he did suggest Ginger because I’ve always wanted to play with the two of them – most guitarists would. Ginger came in and it was obvious it had to be a band, it couldn’t be just my name on it.

"It was so easy to work with them in the studio, the whole thing was just great and the album took no time at all. We got a new deal and the whole thing went from there, but because of my background and because of their backgrounds it was seen as a poor man’s Cream.

Let’s face it, it would have been a bit weird if it didn’t sound a bit like Cream, with a guitarist who grew up listening to Eric and Peter Green and Jack and Ginger Baker

Let’s face it, it would have been a bit weird if it didn’t sound a bit like Cream, with a guitarist who grew up listening to Eric and Peter Green and Jack and Ginger Baker. I mean, what do you expect it to sound like?

“The shame of the whole thing was that it was a bloody good band. I’ve got tapes of some of the gigs and it was great. We did some shows in Spain and the crowds loved it, we had such a great time on stage, but the media just perceived it as this very superficial thing, which it wasn’t. I just don’t think people were ready for that band at the time but I’m still very proud of what we did together and I always will be.

"I’ve no regrets about doing it whatsoever because it was such a great musical experience to work with Jack on a more permanent basis and to work with Ginger who’s the finest drummer I’ve ever played with, he’s absolutely amazing.

“But it’s over now, finished. I might do some work with Jack again but there was just too many things against us really to continue, so we had to finish when we did. There were a lot of things within the band that would have made it impossible, long term. I think that politically Jack was used to having his own band, I was used to having my own band and so it was very difficult.

"Jack always considered it to be my band, which it was and it wasn’t, I kind of helped set the whole thing up and everything so I think he was very uncomfortable with that which is fair enough. He’s always had his own bands and he likes to call the shots and I like to do the same thing.

"We’re both quite headstrong in that way, so there was a bit of friction. But at the end of the day I don’t have a bad taste in my mouth about it at all. I feel like I can call Jack up and if he wants me to do anything I’ll do it for the guy – and I’m sure it works both ways. In fact we’ve worked together since then: he played on a couple of tracks on Ballads And Blues. I said to him, ‘If you want any guitar on your next album, just call me – I’ll send Eric over!’”

Since your blues renaissance a few years ago, you’ve worked with many legendary figures including BB King and Albert Collins. Are there any players you’d still like to work with?

“Not many of them left… I really enjoyed working with BB King because I think a lot of his style was handed down to me through Peter. Obviously he was into BB and everything and so when I play with him I feel he’s a lot easier to play with stylistically than say, Albert King or Albert Collins because you can relate a lot more to what he’s doing.

"For a start we both play in standard tuning, whereas the other guys had their own ways – totally alien ways of playing – and the more you try and play like either of the Alberts really, you’ve got no chance. I mean, nobody could play like Albert King, I’ve never heard anyone get really close. Stevie Ray could to a certain extent, but if you look at it there’s no way you could play like those guys because it’s such an unorthodox way of playing.

"Albert King’s tuning alone is just the weirdest thing and the fact that he’s playing upside down, pulling when you’re pushing, it’s like – you can’t win! And Albert Collins – no one could play like that except him and he knew it.

"He told me that it went back to when he had no bass player and it was just him and a drummer, so he’d have to fill the sound out, try and play the bass at the same time. So it all came out of necessity for him I don’t know where the F minor tuning came from, that’s still a bit of a mystery to me.”

Albert Collins would come on and I’d stand back and play one chord every couple of bars and watch him, and I learnt nothing!

Not to forget the other remarkable facet of Albert Collins’ playing, his capo.

“Ah yeah. It was just, Hey what key are we in?” he laughs. “He didn’t give a shit what key it was in, which made me think, why would he tune to F minor to begin with?

"Why not E minor and go from there? He used to listen to different music as well and he used to play some country stuff; it wasn’t just blues when he started out, but he was amazing just to be around. I remember when we did the Still Got The Blues tour, he played with us for four months or something so I was up there every night with him and a lot of the time I wouldn’t bother to play, he’d come on and I’d stand back and play one chord every couple of bars and watch him, and I learnt nothing!

"It wasn’t until about a year or two afterwards that the influence started to come through. That’s the weird thing, you know, hard as I tried to be like him on the tour – nothing. It wasn’t until I got away from the whole thing that I was able to pick up a few things that he did and even then it was very fragmented. Just the attack on the notes and stuff like that, and a bit of phrasing, but that’s as close as I ever got.”

After severing all connection with all things metal have you now established a musical direction that you’re happy with?

“Well no, I wouldn’t say that. I’m never wholly happy with anything I do, otherwise I wouldn’t bother. I think it’s nice to be considered as a blues musician and it was probably the best move I’ve ever made.

"The idea of being 45 years old and wearing spandex just doesn’t happen for me, you know? I had to sidestep it somehow and get away from the whole thing because I was so bored with it. I hated it and I hate it even more now because it’s got even worse as far as I can make out. It’s like cartoon music or music for computer games a lot of the time.”

I love Eric’s playing, if it wasn’t for Eric, this world I live in wouldn’t exist

Do you ever see yourself doing a blues project like Clapton’s From The Cradle, where authenticity is the watchword?

“I don’t know, it’s something he does so well because he’s more of a historian than I am. He’s always been more into that whereas I’ll always just enjoy listening to it and playing it. I don’t claim to be an expert on the blues or anything whereas Eric – you could talk to him about any aspect of the blues and I’m sure he would know the whole history of it, which is probably why he did the album like that, more of a history lesson.”

For all the comparisons, you’ve never played with Clapton…

“No, he’s never asked me! And I don’t think he will – I think I’m the only one he hasn’t asked. But listen, I love Eric’s playing, if it wasn’t for Eric, this world I live in wouldn’t exist. When I heard the Bluesbreakers album, like a lot of guitarists of my generation, that was the thing that turned the world upside down for me.

"When I heard that guitar that was as powerful for me as Robert Johnson was for Eric. To hear a guitar become the main voice in the music and to be that forceful and so direct, it was amazing, there was nothing like that before and nothing like it since either, really.”