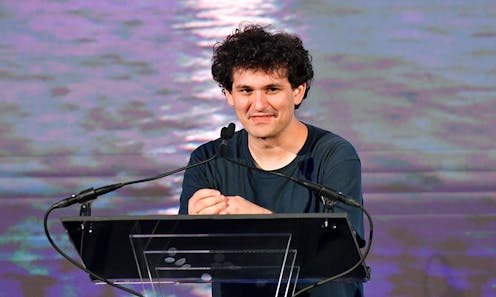

FTX, an exchange for trading cryptocurrencies, quickly became bankrupt and defunct in November 2022. Its founder, Sam Bankman-Fried, is broke, and the 30-year-old former billionaire could be in serious legal trouble for his alleged financial improprieties. The Conversation asked Brian Mittendorf, an accounting scholar at The Ohio State University, to explain the significance of FTX’s implosion for philanthropy and the nonprofits Bankman-Fried supported.

What was the connection between FTX and philanthropy?

Though FTX was a cryptocurrency exchange, Bankman-Fried viewed it as something more: a vehicle to change the world through giving. Bankman-Fried often noted that his goal for his business was to make money in order to donate it to support a variety of social causes like global health and investigative journalism. Bankman-Fried was also a major donor to politicians in the Democratic Party, while FTX co-founder Ryan Salame gave millions to Republicans.

Bankman-Fried was an acolyte of Scottish philosopher William MacAskill and the effective altruism movement, which emphasizes causes that its supporters believe can do the most good. Many effective altruists “earn to give,” trying to make as much money as they can in order to maximize their charitable impact. In recent years, a growing number of effective altruists have also championed “longtermism” – the view that giving to causes that donors believe will greatly benefit future generations is a higher priority than meeting current needs.

The lines between FTX, the FTX Foundation – Bankman-Fried’s philanthropic collective – and a longtermist offshoot of that foundation called the FTX Future Fund were blurry. The promises for big giving, however, were clear, with Bankman-Fried pledging to donate the bulk of his fortune to assorted causes.

What’s the most immediate fallout of FTX’s demise for charities?

Soon after FTX collapsed, the FTX Future Fund’s entire staff resigned.

The team cited concerns about the legitimacy and integrity of FTX’s operations. By quitting as a group, the staffers signaled that the fund had halted disbursements, while also attempting to distance the broader effective altruism movement from its most famous adherent.

Though Bankman-Fried and his FTX-affiliated philanthropic endeavors were only getting started toward meeting their lofty ambitions, many charities and other organizations had already received funding, and many had obtained further promises for future funding. Those commitments now seem unlikely to ever be disbursed. Many recipients, including ProPublica – a nonprofit investigative media outlet – are no longer counting on receiving those funds.

All signs point to much of that promised giving being unlikely to materialize.

Can charities be forced to relinquish any donations tied to FTX that they have received?

What might happen to the money that had already been disbursed is less clear.

The possibility of it being “clawed back” from the causes that received funds from FTX affiliates or Bankman-Fried himself is real but less likely. Funds given in the 90 days prior to bankruptcy are the most likely to be vulnerable to claims in bankruptcy, but other gifts could be at risk too, if the activities of Bankman-Fried or FTX are found to be fraudulent. Even in that case, however, charitable gifts are given extra protection, limiting the likelihood of such a “claw back.”

What will the FTX fallout mean for cryptocurrency donations?

Charities have become more adept at receiving cryptocurrency donations over the years, primarily due to a multiyear boom in crypto markets and tax considerations that can make it advantageous for crypto investors to give away some of their large, untaxed gains.

In 2022, that boom gave way to a crypto bust, which has only gotten worse in the aftermath of FTX’s collapse. I believe it will reduce the flow of crypto to charities to a trickle – at least for now.

The FTX collapse also highlights the inherent risks charities face when they hold onto crypto assets and engage with these largely unregulated markets. The Silicon Valley Community Foundation, a charity which pools resources for the benefit of northern California, has seen fluctuations in values of its crypto holdings to the tune of billions of dollars. Other charities have shown themselves eager to join the craze as well. The FTX fiasco may prompt charities to think twice before seeking crypto gifts or holding onto cryptocurrencies instead of liquidating them as soon as possible.

What does this whole episode say about philanthropy?

Though the failures at FTX may not indicate similar failures are imminent, either in crypto markets or in effective altruism efforts, they do highlight some of the risks.

FTX operated in a lightly regulated environment, and Bankman-Fried’s brand of effective altruism was praised for being both visionary and disruptive. Together, these features highlighted an ethos of philanthropic giving that, by favoring big bets and bold goals, adopted the big-tech mantra of moving fast and breaking things.

In my view, FTX’s epic failure highlights the value of being transparent and accountable, both in business endeavors and giving. Minding the nitty-gritty details, heeding regulatory obligations and giving to established organizations may seem humdrum, but it’s worth the trouble and is surely more “effective” than the alternative in the long run.

As details about FTX’s demise came to light, a very different new and highly visible megadonor briefly made one of her intermittent appearances in the news. MacKenzie Scott, a novelist who was married to Jeff Bezos when he launched and built up Amazon, announced on Nov. 14, 2022, that she had given nearly US$2 billion in the previous seven months to charities that work directly on acute community needs, like many local chapters of Big Brothers Big Sisters of America and the National Urban League.

Although Scott isn’t operating a traditional foundation and she has bucked many philanthropic conventions with her emphasis on social justice, her approach and record stand in stark contrast to Bankman-Fried’s.

Brian Mittendorf does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.