The University of Illinois at Chicago in its original form was a bold and mysterious place when it opened in the mid-1960s on the city’s West Side.

The idiosyncratic campus of modernist buildings linked by elevated concrete walkways, with a huge outdoor amphitheater called the Circle Forum at its center, was disliked by more than a few.

Then-Sun-Times architecture critic M.W. Newman famously dubbed the campus “Fortress Illini.”

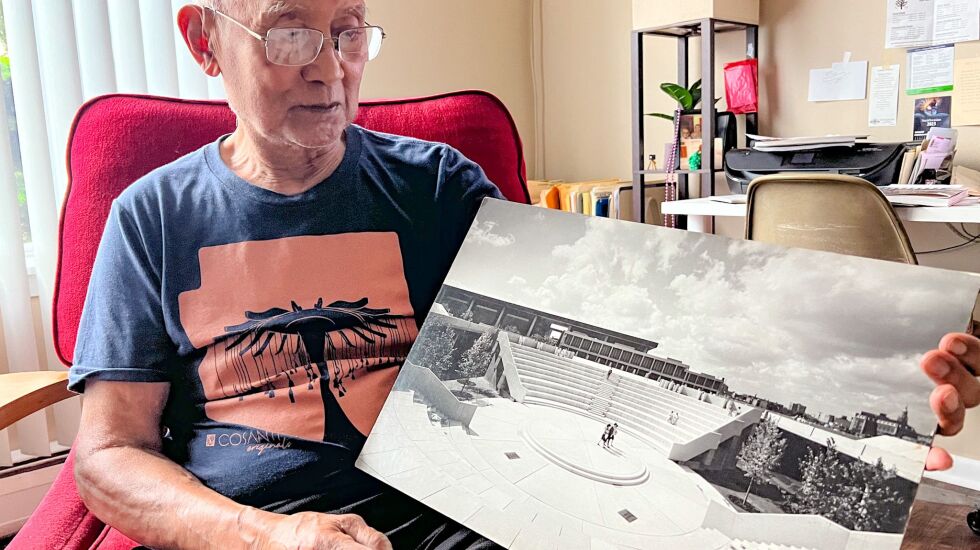

But photographer Orlando Cabanban, hired by architect Walter Netsch of SOM to document the new university, saw things differently.

Cabanban’s photography depicted a bustling campus of unique buildings — a counterpoint to the criticism UIC had received.

“I liked the design,” Cabanban, now 89, says with a smile.

A licensed architect who switched to photography early in his career during the 1960s, the Chicago-born Cabanban was hired by top architecture firms to document their work.

And while he didn’t become as well-known as architectural image-makers such as Hedrich-Blessing, or Ezra Stoller, his UIC work alone shows he could give them a run for their money.

If you find midcentury images of signature buildings such as Marina City or Seventeenth Church of Christ, Scientist at 55 E. Wacker Dr., it’s likely Cabanban was behind the lens.

In 1995, as part of the Art Institute’s Chicago Architects Oral History Project, interviewer Betty Blum asked Netsch who was his preferred photographer.

“Well, I had three,” Netsch said. “The photographer Balthazar Korab from Detroit … And our local photographer Hedrich-Blessing. The other one was Orlando Cabanban.”

Architecture and more

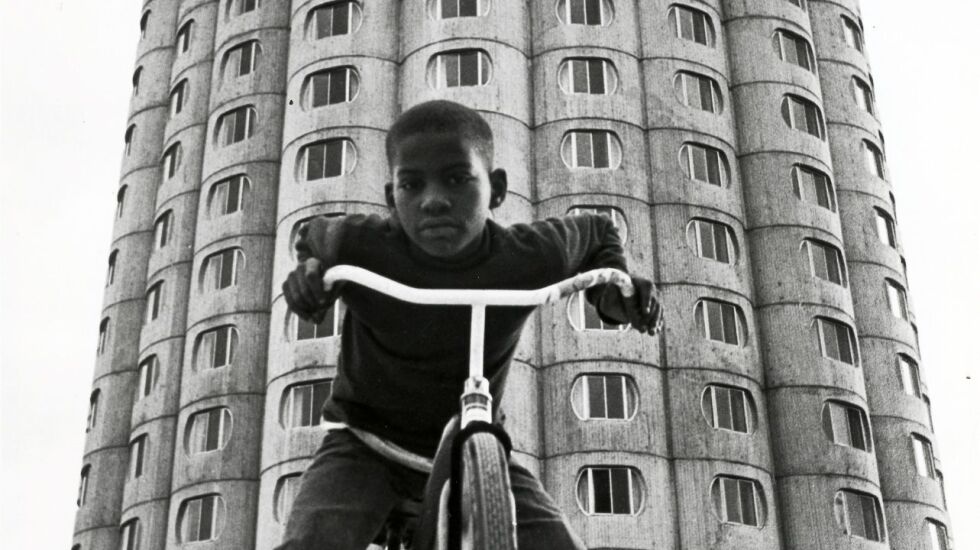

Cabanban photographed the Raymond Hilliard Homes, 30 W. Cermak Rd., for architect Bertrand Goldberg in 1966.

The photographer captured Hilliard’s curves, shooting parts of the cylindrical development through its lozenge-shaped windows.

But the standout of the Hilliard bunch is a low-angle shot of a young boy on his bicycle, peering down into Cabanban’s camera while a 15-story Hilliard senior citizens building looms behind him.

“I saw him riding around and just asked him to pose,” Cabanban remembered. “I was there photographing the construction of the buildings.”

Architecture photographers of the time frequently didn’t include people in their images — the design is the thing — but Cabanban was among the exceptions.

As Netsch told Blum: “Orlando would always photograph with people, and I like that.”

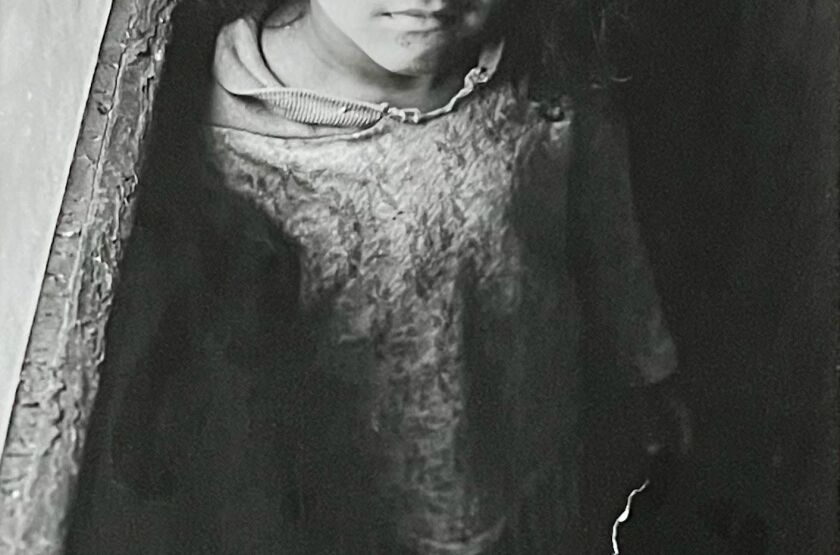

Placing individuals within his architectural photography also illuminates a lesser-known part of Cabanban’s career: He documented people as a street photographer, and on assignments for the Field Museum and the Community Renewal Society.

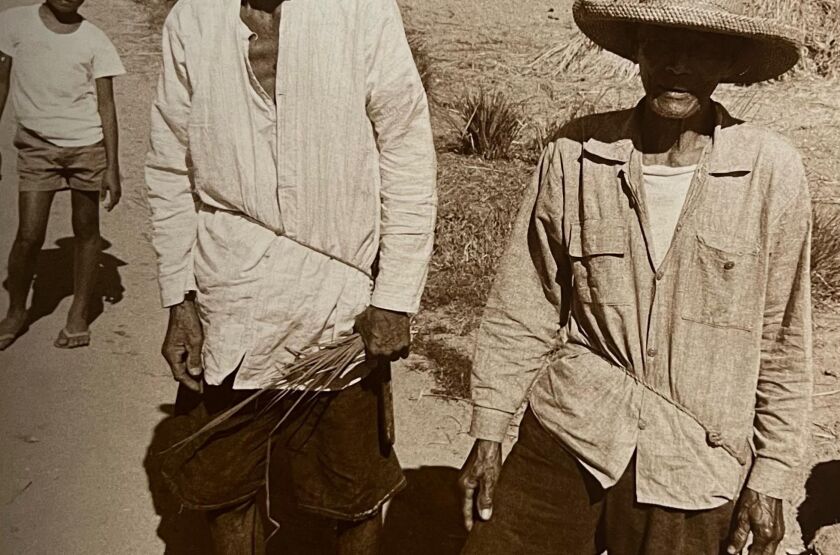

Cabanban also traveled to the Philippines to photograph family members and the town in which his father was born.

He also photographed a 1966 Loop demonstration led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

“I think I favor the people photographs,” Cabanban said. “That was my first love.”

For the Field, Cabanban photographed Mexican Americans living in the south suburbs during the 1960s. The photographs show weddings, gatherings in the park — even some cattle-wrangling event.

The museum also assigned Cabanban to document Native Americans in Chicago and in the Southwest.

“I went to the powwows, and I danced. I learned to dance just, you know, just going around in a circle, pounding my feet,” Cabanban laughed.

Perhaps a photographic story to tell

UIC looks more traditional today. There are some new buildings, and the walkways and Circle Forum were removed in the 1990s.

Cabanban’s masterful images of UIC — seen around the world at the time — remain the best and most thorough photographic record of the original out-of-this-world campus.

Meanwhile, Cabanban has put down the Nikons, Hasselblads and Sinars and retired from photography.

“No, I don’t shoot anymore,” he said. “I photograph my grandchildren though, once in a while when I get a good camera in my hands.”

Cabanban wonders if a book of his work might be in order. In addition to SOM, Goldberg and Weese, Cabanban’s client list reads like an architectural who’s who of the era, including the likes of Perkins & Will and Mies van der Rohe.

Here’s hoping it happens. Packaged the right way along with Cabanban’s street and ethnographic photography, it could all make for a compelling new look at the people and places of 20th century Chicago.

Lee Bey is the Chicago Sun-Times architecture critic and a member of the Editorial Board.

Send letters to letters@suntimes.com