The ticking clock is becoming louder within Canberra's prison system, with an ambitious government target set in pre-pandemic years now appearing ominous for the newest appointee to the top job in ACT Corrections.

Running a prison system of just one jail, into which every offender refused bail by the court system is tipped, could be quite legitimately described as one the toughest roles in the ACT government.

No longer having a dedicated remand centre as a buffer, murderers, rapists and bikie enforcers rub shoulders with public service fraudsters and other non-violent white collar criminals behind the tall, chain-link fences at the Alexander Maconochie Centre in Symonston.

Incomplete separation of detainees linked to a revolving door of prisoners on remand - an unsettled population, coming and going from court, uncertain of whether the cell doors will be locked on them for months or years - makes for a difficult mix and one of many challenges faced by the new ACT Corrections Commissioner.

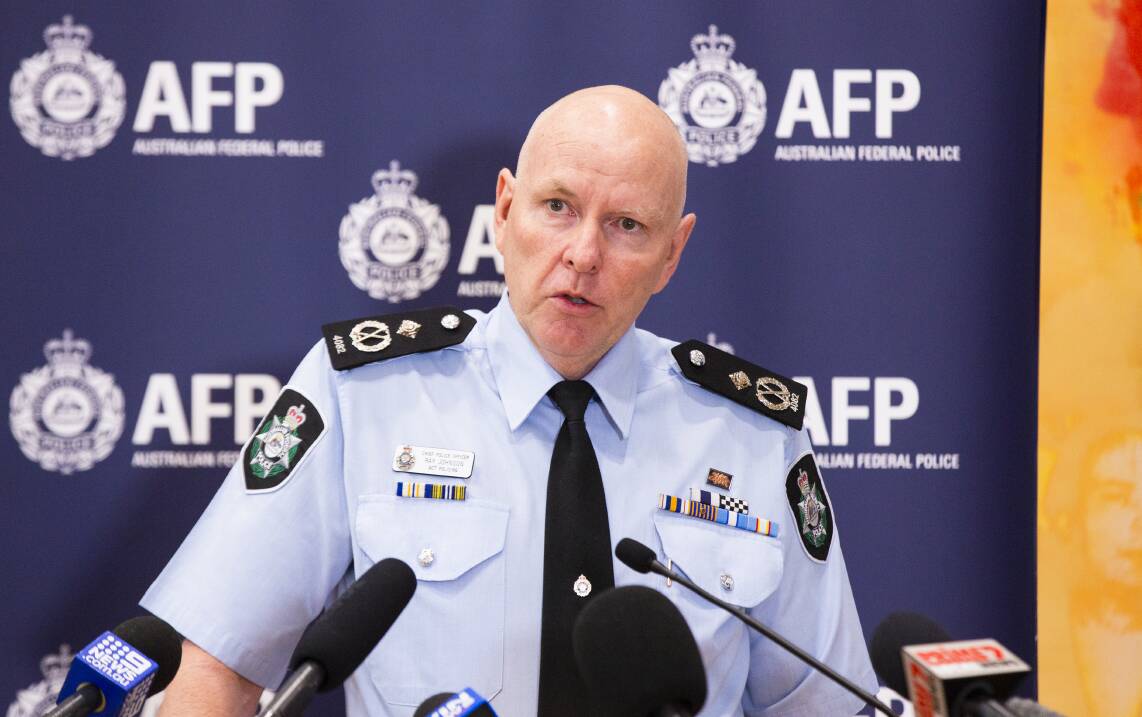

Ray Johnson does not have a Corrections background, which makes him something of an outlier among other prison chiefs around the country. And while he easily could have sought out a much-less pressured role, he remains motivated by the old-school policing principles of serving the community and "making a difference".

Described within the ranks as a "decent, caring bloke", he's a former career police officer who rose to assistant commissioner with the federal police, became ACT's Chief Police Officer for a short time, then found his way across to the ACT's Emergency Services Agency when, as is often the case within the federal police, the arrival of a new Commissioner pushed a broom through the senior executive ranks at the AFP's Barton headquarters.

He's now very much back in the firing line, with a raft of stakeholders - far more, he admits, than he has experienced before - watching and assessing his every decision.

Just appointed to a five-year contract to run the ACT's troubled prison system, Commissioner Johnson has a only a short time in which to make significant inroads into one of the territory's most pressing issues: recividism.

And as a reference point, he only has to look at how quickly his predecessor, Jon Peach, was shuffled out of the job when progress stalled and prisoners rioted. While Mr Peach was given a handsomely paid safety net well out of the public eye, his rapid departure offered proof that in the prisons business, tenure can be very tenuous indeed.

In 2020, the ACT government announced the bold goal of reducing the recidivism rate from 42.4 per cent to 31.7 per cent, a goal airily described as effectively changing "the life trajectories of some of Canberra's most vulnerable citizens".

While recidivism is a national issue, over recent years the ACT has compared quite badly against other jurisdictions.

In its compilation of prisoner data last year, the Australian Bureau of Statistics found that 77.6 per cent of inmates in the ACT system had been imprisoned previously, with very little change from the previous three years. This compared with 59.9 per cent nationally.

Only this week, the head of the Winnunga Aboriginal Health Service, Julie Tongs, took the new Commissioner to task on social media for "lies, damned lies and government statistics" on the government's manipulation of recidivism rates of indigenous prisoners, and urged a Royal Commission.

The ACT Corrections systems is a complex one but front and centre is the Alexander Maconochie Centre which opened in 2008 with lofty ambitions but has become increasingly burdened with a bulging population, and beset with a myriad of issues which, it appears, can only be properly addressed through significant investment in new infrastructure and rehabilitation programs.

One of the proposed infrastructure projects to slow the revolving door was the $71 million 80-bed Justice Reintegration Centre announced in 2021. It is now all but dead in the water.

With the ACT government spending up big during the pandemic and the territory's economy mired in $5.7 billion of debt and expected to blow out to $9.5 billion by 2025, spending money on prison infrastructure appears to have been shuffled well down the wish list.

Back in 2019, the former Corrections Minister Shane Rattenbury was disarmingly upfront about the hill that the ACT jail had to climb, declaring "the [Canberra] prison was built too small and without industry, and we've been playing catch-up ever since".

The arrival of the COVID pandemic thrust a stick in the spokes of Commissioner's Johnson's plans for better engaging the Transitional Release Centre in diverting people out of the justice system, and away from his prison gate. The TRC could be the key gateway to easing detainees back into the world outside the wire, but has been enormously under-utilised.

"Trying to keep COVID as best we can out of the [prison] facility, we adopted our practices as best we could. We've been able to allow people out to do banking or go for job interviews but not overnight, at this point," Commissioner Johnson said.

"Once we get ourselves fully functional post-COVID, people will be able to do potentially more extended periods of job experience or family visits [away from the prison]."

He says that tackling recidivism is about knitting people from a highly institutionalised, regimented environment back into the community in a better way.

"So many of these things work on an individual basis," he said.

"It's very hard to say a particular [release] plan is going to work for everyone. You've got to put a plan in place but tailor it to an individual [and] that's an intensive exercise.

"Where I think Corrections can add great value is from the time someone becomes an offender - when they are sentenced, not necessarily to AMC but perhaps through a community corrections order - to the time they stop becoming an offender, we should have their best interests at heart.

"The challenge is always to get the best outcomes for people, but their pathways are very rarely the same.

"Everyone's journey [through the justice system] is different. And you need good, talented and passionate people [in justice systems and support networks] to help broker that journey."

We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on The Canberra Times website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. See our moderation policy here.