After a year in which war ravaged Ukraine, stubbornly high inflation brought the global economy to the brink of recession, a “tripledemic” revived pandemic fears, and limited progress was made on the climate crisis, it would be understandable to approach 2023 with a sense of unease.

And yet a series of scientific breakthroughs in 2022 are bringing reasons for optimism for the new year.

From fusion energy to improved vaccines and organ transplants, an artificial intelligence revolution to diverted asteroids, technologies previously found only in science fiction came to fruition.

Those landmark discoveries, some the culmination of decades of work, offer grounds for hope.

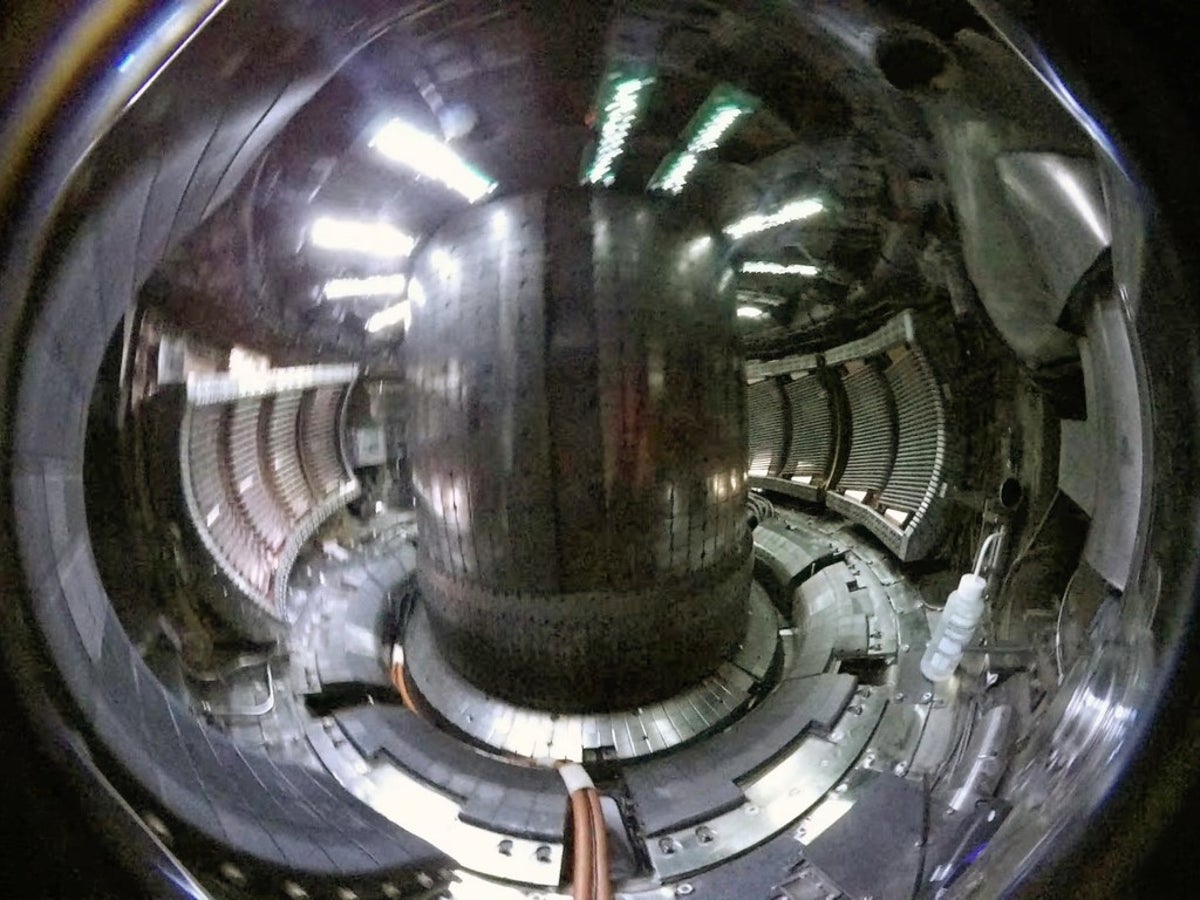

Nuclear fusion’s ‘holy grail’

In mid-December, scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California announced they had carried out the first nuclear fusion experiment that created more energy than had been used to start it.

Described as a “shot for the ages”, the historic achievement involved harnessing the same reaction that powers the sun and stars to produce zero-carbon energy for the first time.

The technology has been pursued since the 1950s, and spurred excitement about the prospect of replacing fossil fuels with a climate-friendly, renewable energy source.

Department of Energy (DOE) secretary Jennifer Granholm described the breakthrough as “one of the most impressive scientific feats of the 21st century”, on a par with the Wright brothers’ first flight in 1903.

According to the DOE, a fusion reaction involves pushing two nuclei particles from a lightweight element together at enormous speed, fusing them together. The resulting mass produces a large amount of energy without creating much radioactive waste.

As The Independent reported in January, decades of research and billions of dollars have gone into trying to create this “holy grail” of nuclear reactions.

Secretary Granholm said the breakthrough has suddenly made possible the prospect of an abundant, carbon-free energy source for the future.

The poetry of artificial intelligence

The release of ChatGPT in November offered a glimpse of a future where computer-generated prose can provide the answers to a seemingly infinite number of questions.

Want to know how Shakespeare would describe looking at the stars? Maybe you’ve got a tricky technical question about quantum physics? Perhaps you want to know how to build a footwear wardrobe suitable for any climate? Or learn how to play the piano?

Developed by OpenAI and free to use – for the moment at least – ChatGPT has been described as a revolution in artificial intelligence, almost as if you were having a direct conversation with Google.

The beauty of this chatbot is that it sifts through billions of data points in seconds, saving users from the task of trawling the web looking for the precise piece of information they’re after.

The answers seem personal and human, as if the machine on the other end has carefully considered and tailored its answer.

It can have its limitations, though. As OpenAI acknowledges, ChatGPT will often confidently write plausible-sounding responses that are incorrect or nonsensical.

Educators are also warning of the potential consequences of cheating in exams and essays.

But there are many real-world benefits: it can assist computer programmers to spot bugs in coding, guess medical diagnoses, and even write jokes.

It has also taken steps to avoid being misused for bigoted and racist purposes.

OpenAI was launched in 2015 by a group including Elon Musk and CEO Sam Altman, and is backed by Microsoft and several venture capitalist firms.

The New York Times called it “quite simply, the best artificial intelligence chatbot ever released to the general public”.

While it may not be open to general use for long, it’s a fun way to come up with a new recipe for your favourite home-cooked meal, or choose a movie to watch.

Diverting asteroids

In the 1998 movie Armageddon, Bruce Willis and his band of roughneck oil drillers are sent into space by Nasa to insert and detonate a nuclear bomb into an asteroid that is about to wipe out humankind.

Twenty-four years later, the US space agency’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test team proved that deflecting an asteroid from its path was not only the stuff of Hollywood.

In September, Nasa sent a spaceship smashing into a 525ft-diameter asteroid Dimorphos at 14,000 miles (22,530kms) per hour, to find out whether it was possible to alter its trajectory.

Dimorphos was not on a civilisation-threatening collision course with Earth, but rather orbiting around a larger asteroid, Didymos. Prior to the crash, Dimorphos was circling its parent asteroid every 11 hours and 55 minutes, while afterwards its orbit was timed at 11 hours 23 minutes.

This marked the first time humanity had deliberately changed the “motion of a celestial object and the first full-scale demonstration of asteroid-deflection technology”, Nasa said.

Nasa administrator Bill Nelson said that the mission showed his organisation was preparing for “whatever the universe throws at us”. Hea added: “All of us have a responsibility to protect our home planet. After all, it’s the only one we have.”

The James Webb Telescope

The launch of the James Webb Telescope brought vivid imagery from the dark recesses of the galaxy into full view in 2022.

Hailed as the Innovation of the Year in aerospace technology by Popular Science magazine, the $10bn telescope “can see deep into fields of forming stars” and peer “13 billion years back in time at ancient galaxies, still in their nursery”.

Since it first began sending its spellbinding images back to Earth in February, the James Webb Telescope has been teaching scientists how “stars and galaxies came together from primordial matter”, Popular Science magazine notes.

Unlike the Hubble Telescope, which orbited close to Earth, the James Webb was launched hundreds of thousands of miles further out and sits in the Earth’s shadow, which permanently blocks it from sunlight.

Since its launch, the James Webb Space Telescope has found the oldest galaxy in the known universe, as well as photos of the Carina and Southern Wheel nebulae, a collection of galaxies known as Stephen’s Quartet, and a spectrum of light from the exoplanet WASP-96b.

Universal flu vaccine

Facing a spike in Covid-19 cases, and a possible “tripledemic”, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have created a flu vaccine based on mRNA molecules that were used to create Covid vaccines to fight back against the coronavirus pandemic. Experts revealed in December that immunisations of mice and ferrets had produced antibody responses to all 20 known influenza A and B virus strains that last four months, Science magazine reported.

With Covid-19 cases rising again, respiratory syncytial virus clogging hospitals and the winter flu season on track to be the worst in 10 years, the vaccine could prove crucial to avoiding widespread deaths. Already, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have reported in excess of 4,500 deaths this season.

As the flu evolves every season, creating an effective vaccine has proved elusive. But building on the same mRNA technology that’s used in Covid-19 vaccines, researchers believe they could be on the cusp of offering an effective vaccine for influenza.