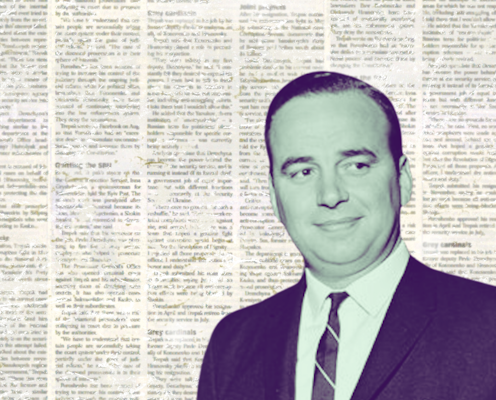

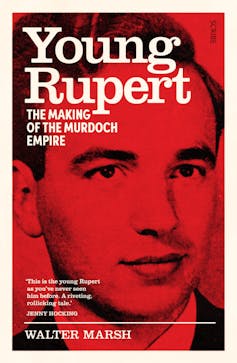

Nearly every biographical commentary on Rupert Murdoch notes how he began with a modest inheritance in Adelaide, principally an afternoon newspaper, and built it into a global multimedia empire. Walter Marsh’s book Young Rupert: The Making of the Murdoch Empire has the distinctive strength of knowing Adelaide much better than any other Murdoch watcher, and studying Murdoch’s Adelaide period in more depth than anyone else.

Review: Young Rupert: The Making of the Murdoch Empire – Walter Marsh (Scribe)

Rupert’s father, Sir Keith Murdoch, was the most famous Australian newspaperman of his generation. As the dominant figure in the Herald & Weekly Times group for over two decades, he built the country’s first newspaper empire.

But he increasingly resented the chasm between being a shareholder and an employee, no matter how well rewarded. He was determined to leave his son Rupert a tangible inheritance. In the last years of his life, he sought to build his own independent newspaper empire in ways that were far from being in the best interests of the Herald & Weekly Times.

Sally Young’s recently published Paper Emperors: The Rise of Australia’s Newspaper Empires gives a very good account of Keith’s machinations. Rupert would never have allowed any employee of his to behave in the way Keith did.

A great fight

After all Keith’s efforts, once the personal debts and death duties were paid, Rupert’s inheritance essentially came down to the Adelaide News. Editing the Adelaide News was Rohan Rivett, Keith’s trusted confidante and Rupert’s mentor and friend from his Oxford days.

Rivett was a distinguished journalist, who had recorded his experiences as a prisoner of war in Behind Bamboo, the bestselling Australian book on World War II. His political leanings were to the left. The Adelaide News was seen as bringing a refreshing degree of social and political liberalism to South Australia’s stuffy politics, although the paper rarely directly challenged the premier, Sir Thomas Playford, by far the longest reigning state premier in Australian history (1938-1965).

Almost immediately, the Herald & Weekly Times morning newspaper – the very establishment Advertiser – sought to drive News Limited out of business by starting a rival Sunday newspaper. Rivett and Rupert fought hard to survive. Not for the last time, Rupert relished the conflict. “It is going to be a great fight,” he told Rivett.

In a front page editorial, Murdoch and Rivett disclosed the behind the scenes actions of their rivals. After a couple of years, the two Sundays fought each other to a stalemate. In the subsequent agreement, in some ways News emerged the better. Rivett and Murdoch had won their first big challenge.

With this threat disposed of, Murdoch, now with the title “publisher”, began his expansion. He bought the Sunday Times in Perth, where free from Rivett’s presence he was more able to indulge his tabloid tastes.

He also successfully applied to get one of the first two commercial television licences in Adelaide, although his lobbying to make this a commercial monopoly service failed.

Marsh deftly documents how Murdoch’s views on the virtues of monopoly and competition varied to suit his immediate interests. Murdoch’s declaration, when he unsuccessfully applied for the first commercial television service in Perth, that he was not interested in building his empire, has not exactly stood the test of time.

Two episodes

The two episodes that later writers always mention about Murdoch’s Adelaide period are the News’ championing of the cause of Rupert Max Stuart, convicted for the rape and murder of a nine-year-old girl, and his firing of Rivett.

Stuart was an itinerant Aboriginal labourer, illiterate, with limited English and prone to alcoholic binges. In December 1958, he was arrested near Ceduna and charged with the murder. The case for conviction rested principally on his confession.

With the threat of imminent execution hanging over him, Stuart had his cause taken up by Father Tom Dixon. A pamphlet by the historian Ken Inglis and coverage in the Adelaide News, driven by Rivett and supported by Murdoch, forced a new trial and then a Royal Commission.

The newspaper’s coverage of the Stuart case became politically controversial and the Playford government brought nine charges against it, including seditious libel. After a prolonged period of suspense, these charges were dismissed.

Putting to one side the drama, uncertainty and high emotion of the case, there are, in retrospect, three groups of opinion on Stuart’s conviction.

First, there are those who think he was guilty and the police and officialdom were essentially correct in everything they did. The second group consists of those who continued to believe in Stuart’s innocence, including Father Dixon and, years later, the investigative journalist Evan Whitton. The third group believed that the police grossly mistreated Stuart and fabricated the case against him, but that he was probably guilty.

Ken Inglis’s book concluded that the weight of the evidence tilted toward guilt rather than innocence. Decades later, Murdoch said:

There’s no doubt that Stuart didn’t get a totally fair trial, although it’s probable that he was guilty. I thought this at the time.

I think Murdoch is overstating the constancy of his opinion here. My guess is that, initially, when Rivett and Inglis took up the cause and later recruited Murdoch to it, they thought Stuart was innocent. After a searching cross-examination of Stuart at the Royal Commission, several of his previous supporters had their beliefs shaken.

The action that most showed Murdoch’s ruthlessness in these years was his sacking of Rivett in 1960. Rivett had been the editor of Adelaide News for eight and a half years. He had given the paper a much stronger financial basis, as well as higher standards of journalism. Before that, Rivett had helped Rupert through his years at Oxford. Relations were almost familial. They went on holiday together and Rupert often stayed with the Rivetts in London.

Despite the close and generally amicable relations between them, Murdoch fired Rivett without warning. Murdoch’s brief letter gave no reason for the dismissal and was never preceded or followed by any personal discussion between the two.

Murdoch later claimed that even after the trauma of the Royal Commission and libel trial, Rivett was being too provocative in his attitude to the Playford Government. Marsh notes that the last month of Rivett’s editorship gives no grounds for such a claim.

The timing, I think, was determined not by events in Adelaide, but by Murdoch’s bid for the Daily Mirror in Sydney. As Marsh points out, Rivett was a friend of the unions, and more inclined to be generous towards the journalists in his employ. Murdoch, with his eyes on Sydney and beyond, wanted his Adelaide assets to be a safe and regular cash cow to aid his ambitions for expansion elsewhere. A quiet, frugal editor was what he now required.

The unsentimental firing of Rivett showed that Murdoch was determined to be in sole charge and would pursue his interests ruthlessly.

Murdoch watchers will be also particularly interested in what other clues Young Rupert gives about its subject’s later behaviour. My suggestion comes in February 1956, when he was caught driving at at least double the speed limit on an Adelaide highway. After Murdoch made his excuses, the police allowed him to drive on, but almost immediately he started speeding again in a school zone, and the same police arrested him a second time.

Already, for this 24-year-old, rules were things that only applied to other people.

Rodney Tiffen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.