Cast your mind back to March 17, 2013. On the northwest coast of Italy, somewhere between Milan and San Remo, 200 professional cyclists were facing torrid racing conditions as they battled on to win – or even just finish – La Classicisima against wind, ice, sleet, and snow.

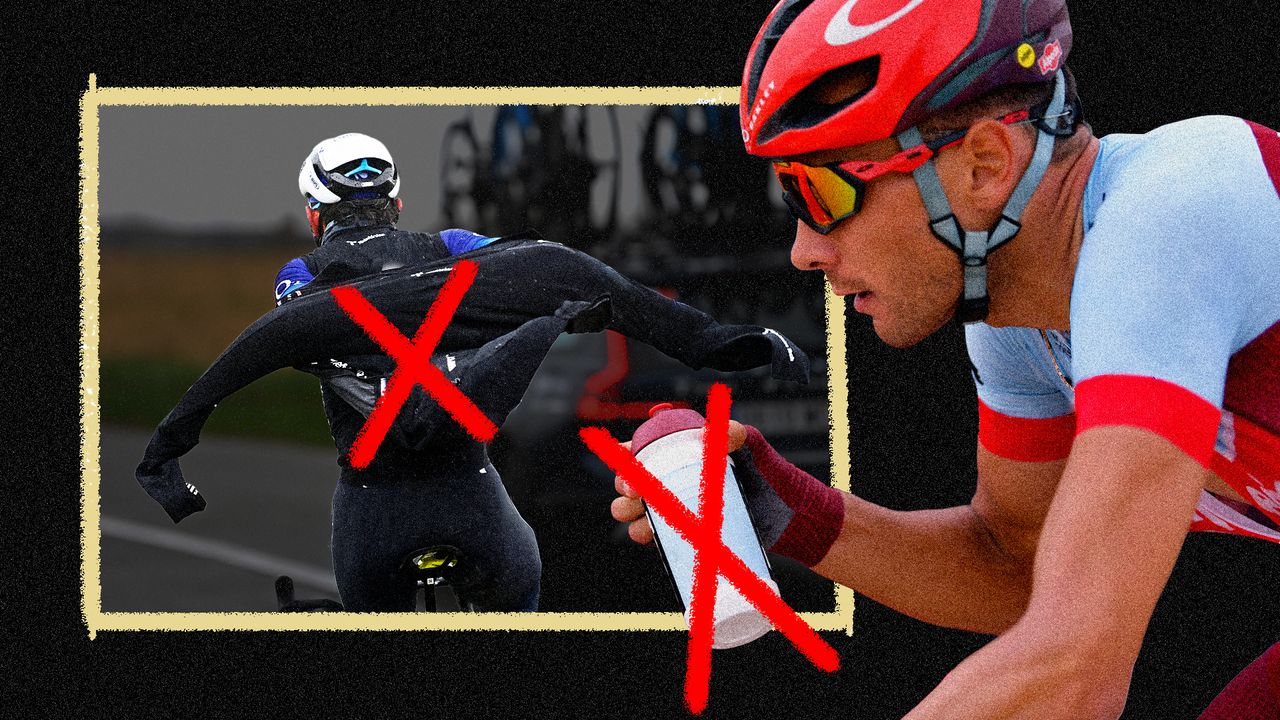

Watching the race back now or looking through epic images of Peter Sagan, Fabian Cancellara, Mark Cavendish, and eventual winner Gerald Ciolek facing all the elements Mother Nature could throw at them, you’ll see – amongst the mass of old school rain capes flapping in the wind and doing little to protect the riders from the wintery conditions – tens of riders wearing a sleek, black jersey which cuts a remarkably aero profile for a rain jacket.

In most cases, the logo was scribbled out with a black Sharpie, but after the race, it became clear that throngs of pro teams had gone out and purchased Castelli’s new foul-weather racing Gabba jersey to keep their riders warm whilst maintaining an aerodynamic advantage.

This is one of the most high-profile examples of professional cyclists eschewing, en masse, their 'sponsor correct' kit allocation in favour of a product that, in their eyes, did a better job.

In the years since the 2013 'Gabba-gate' at Milan-San Remo, such blatant examples of brand disloyalty have been few and far between, at least to the uninformed. Either teams are doing a much better job of concealing the use of non-sponsor correct equipment, or brands are doing a better job of making kit that meets the riders' standards to use in the first place.

But does it still happen? Why do teams stray, and what do brands think when they do? How does a team’s relationship with a sponsor actually work? We spoke to people from every side of the conversation to find out.

"Up until that day, we had only sold about a thousand Gabbas in the whole world, and 150 of them showed up in that stupid race," Steve Smith, Global Brand Manager for Castelli, told me, recalling that infamous Milan-San Remo moment.

"But it wasn’t just San Remo. The entire spring that year was super wet. If you watch Tirreno [the week before Milan-San Remo], you can see [Matteo] Montaguti on AG2R [not a Castelli-sponsored team] off the front all the time wearing a Gabba."

I asked Smith, who was integral to the design of the original Gabba in 2011, if – given the relatively small quantities of Gabbas that were sold before that San Remo – he was aware that the pros had been buying them, or if they’d been out unbeknownst to Castelli.

"We sold some to Team Sky because Gabriel Rasch [AKA Gabba - the primary co-conspirator in the development of the garment] went there after he left Cervélo Test Team. But then we had reports of Thomas Voeckler going into a dealer in France and buying 30 jackets for his entire team. I’ve got photos of Cancellara at the start, getting ready with two Gabbas in the back of his car that he’d bought on the drive down from Bern. Of those thousand Gabbas that we had sold by then, probably 400 of them ended up on pros."

The team-sponsor relationship

These days, it seems teams and sponsors alike are much sharper on ensuring their riders have equipment that meets the required standards whilst also upholding their contracts.

However, I spoke to one pro cyclist who, while remaining anonymous, was happy to speak fairly candidly about the relationship between the team and their sponsors, and his own personal equipment preferences.

"This year we tested the [sponsor's] new road suit. The team did a track day testing all the different skinsuits offered by different brands. We had UAE's, Movistar's, and a few others to test ours against and, to be fair, it actually stacked up pretty well," the rider told me.

"It was just that curiosity thing. The quickest was UAE's – the Pissei product – but against ours, it was only two watts quicker. So we're actually in a decent place. You can't complain too much. I think they would have tried to tweak it and copy a little bit if it was like miles off."

Of course, sponsorship is partly about advertising your product in the pro peloton, but this kind of feedback coming from pro riders is also a large part of what brands want out of a partnership with a team. In some cases, riders using the equipment they're given without complaining can therefore be less helpful for brands.

"Very, very, very few cyclists I’ve met over the years can really do that blue-sky thinking of ‘here's something nobody's ever thought of before’. A lot of the feedback is nuance, small stuff to make an existing product a little bit better," said Smith.

"The riders are super engaged in giving that kind of feedback. In fact, we have to work hard to get ourselves integrated into a team so that the riders will look at us as a partner. At first, the riders look at their sponsors and say, 'OK, these guys pay the bill. Let's not piss them off' and just tell us what they think we want to hear, but if all we get is 'yeah, the stuff is great' then that's not very useful."

But what about if the equipment riders are given isn’t up to their standards? This is usually touted as the reason why we see riders and teams purchasing off-brand gear in the first instance.

"Certainly, last year we definitely did feel that [the clothing wasn’t up to scratch]," continues the rider. "When we were with our previous brand, you could just sort of tell. We never tested it, but you just knew it was like really dated stuff, and that is frustrating. The margins are so fine, and then you're losing more on things that literally just need a bit of R&D. It's just a bit frustrating."

Straying from the sponsor

I was curious to know if any of the gear the rider in question has used in races has ever been off-brand, and how the team felt about it. His response surprised me.

"Two years ago, our previous sponsor's rain jacket was absolutely dreadful. You'd get colder wearing it than if you weren't wearing it. So everyone started buying Castelli stuff and blacking out the logos," he revealed.

"The team doctors had to step in and say, 'This is not right. We're doing all these races, and everyone's getting sick because they're getting too cold', so I was advised to buy one [a Castelli Gabba] by the doctor. I was racing GP Monseré, and it was just gritty, awful conditions. I abandoned it because I was so cold, and I literally ordered this jacket before the race had even finished."

Ironically, Castelli actually has a ‘pro shop’ page on their website, where they sell a few key foul-weather garments completely free of any logos.

"The blacked out logo is best for us, but a lot of riders don't want to go there with the team and the teams don't want the rider to do that, so we have the pro shop. Decathlon CMA CGM bought Gabbas and rain jackets for the entire team," Smith added.

"Van Rysel doesn't really try to play in that space, so I'm sure the team had the okay from Van Rysel. But the individual riders can get their secret kit – we don't push it too hard because the riders that need that kind of stuff should seek us out."

The average male WorldTour professional raced somewhere around 60-70 days in 2025, but what about the other 300 days of the year? Are riders strictly using sponsored gear when they’re out training, putting in the hard graft away from the cameras?

"I've got jackets that I use instead of the team kit when I’m training, and tights as well. I find the teams give you winter tights, but they're like European winter tights – for when it's slightly cold in the South of France or something," the rider tells me. "But where I live, it’s just not cutting it, so I've got Assos tights, and an Assos jacket that's quite good."

In case it wasn’t obvious, the rider’s kit sponsor is not Assos.

Whilst it might be easy to spot the 'wrong' jacket or shoes on a rider, or detect a discrepancy in tyres if you get a closer look at a pro's bike, what about the things that are harder to spot, like sports nutrition?

Despite their team having a nutrition sponsor (that isn't SIS), the rider said: "I'm basically purely SIS. SIS, and then sweets and stuff like that.

"I find nothing really compares to SIS, and it's what I've always done well off of. I'll mix and match, but the Nootropics gel, for example, I find there's nothing really that comes close to that."

How to mitigate against brand disloyalty

Stretching back to the early days of the Slipstream team, when their riders were among the first to wear aero helmets and skin suits in road races, EF Pro Cycling has long been a team at the forefront of looking for competitive advantages through material. One of the team's sports directors, Tom Southam, explained how they and the team's partners managed to stay ahead of the curve without looking elsewhere.

"Everyone wants to go faster, and keep improving – teams and sponsors alike," said Southam.

"These days the approach is to work that bit closer and much more in depth with your own sponsors and have them on board wanting to push the tech forward, than it is to just run off and buy a load of kit from somewhere else."

"I don’t think a team could legitimately take a lot of money and a dramatically inferior product these days, as the riders just wouldn’t buy it and you’d pretty soon end up in trouble if people started trying their own thing."

Alongside his tenacity and enormous engine, in 2025, the team’s star rider, Ben Healy, relied on an equipment setup that left no stone unturned in the quest for speed. Optimised to the nines, he often used POC’s divisive-looking Procen TT/road racing aero helmet, Vittoria Corsa Pro Speed TLR tyres, and a heavily modified Rapha TT skinsuit (complete with cut-off long sleeves safety pinned in place to ensure maximum aerodynamic efficiency).

The thing that stands out is that, amidst the customisation, Healy has ensured every single piece of equipment is sponsor correct. Only a few years ago, this kind of hyper-optimised setup would have been a surefire opportunity for a rider to look at brands outside their usual sponsor roster to make sure they have the fastest possible setup.

For example, in 2017 British team Bike Channel-Canyon – who were sponsored by Le Col clothing for that season – turned heads when they rolled up to the start of a team time trial in the Netherlands in team-branded VeloTec aero skinsuits. Le Col terminated their sponsorship at the end of the season.

Bike Channel-Canyon had obviously gone to that race looking to mix it up with the bigger teams, and saw a result there as more important than remaining 100% sponsor correct.

"I feel like there was this fetishised idea back in the day that if a team went and bought 'something else', it was this hidden secret that would move the needle for them," continued Southam. "You know, riding tyres at Paris-Roubaix with just a black marker pen masking their real branding. That whole 'if you know you know, wink, wink' secret thing. But that is sort of dead in the water now."

It's clear that one of the major reasons these sorts of transgressions don’t occur as often as they used to is the ease of detection and accountability in this age of social media and seemingly infinite streams of 'content creation' across all platforms.

"Every seam, line, bit of ribbing, shoe lace, rain jacket or prototype helmet is catalogued on the internet within moments of it existing and some rider taking a selfie in it, which as young people they cannot not do, it's impossible," Southam added. "Whatever piece of kit that may be is then scrutinised endlessly by people who are really ‘into that kind of thing’. In this world, you just wouldn’t think you could get away with riding on different tyres or wearing a different rain jacket, two of the most common and obvious sins we’ve all read about in the past."

The world of sponsorship has layers to it. From the brands at the top, through team staff, down to the riders – every stakeholder has a different objective when it comes to equipment.

"No sponsor just wants to open a newspaper and be happy that a rider in a team they pay for has their arms aloft in a black and white photo. Teams and sponsors have cottoned on to the fact that what they are paying for isn’t all about winning, but about the story that is created alongside the wins or highlights," Southam concluded.

"Cycling is a high-performance sport, so the technical suppliers and partners of the teams need to be a part of the success of the team based on the quality of the equipment they sell. That is their story. That is why they sponsor. It’s not just plonking a name on a shirt or an iron-on patch on a polo."

It’s not feasible for every single brand that sponsors a cycling team to expect win after win after win. In the age of Pogačar, Van der Poel, Kopecky, and the handful of other generational talents mopping up the vast majority of race victories, brands are more than aware that a large part of the value they can expect to extract from teams comes from the exposure, the content, and the stories.

"If we talked to a hundred amateur cyclists, I'm not sure how many of those would be able to tell me that Pogačar’s kit sponsor is Pissei," Smith remarked.

"Just having a logo on the kit doesn't really do much for you – the benefits come when you're actually engaged with the team and you really build a story around it. It’s two-fold because you also get the product feedback; these kids are out there in all sorts of weather and conditions, and they do in a year what some of us do in a lifetime of testing."

From a team's perspective, the scope of budgets across the men's and women's WorldTours is broad, with teams at the top financially secure enough to be more discerning in the brands they chose to work with, whereas the teams at the lower end of the spectrum are more beholden to the brands who can offer a financial contribution, even if their product isn’t up to scratch.

From speaking to various interested parties, as well as looking out for this sort of thing in the peloton with a keen eye over a number of years, it seems like the defining contributor – at least these days – in whether or not teams use non-sponsored products is budget. The biggest teams with the biggest budgets can afford the best riders and, therefore, attract the best sponsors who have the facilities and budget to research, test, and develop products that meet the standards expected by the riders. Lower-level teams with smaller budgets simply do not have the buying power to bring on the best riders (who are winning massive races and boosting the team's profile), so they are more beholden to the whim of lesser sponsors who, in turn, cannot offer the same level of product.

There's no one party to blame for when riders go astray, and the reasons for doing so are clearly varied, but for whatever reason, everyone involved is definitely making sure that it's happening less, or at least less obviously than on that rainy day in Northern Italy.