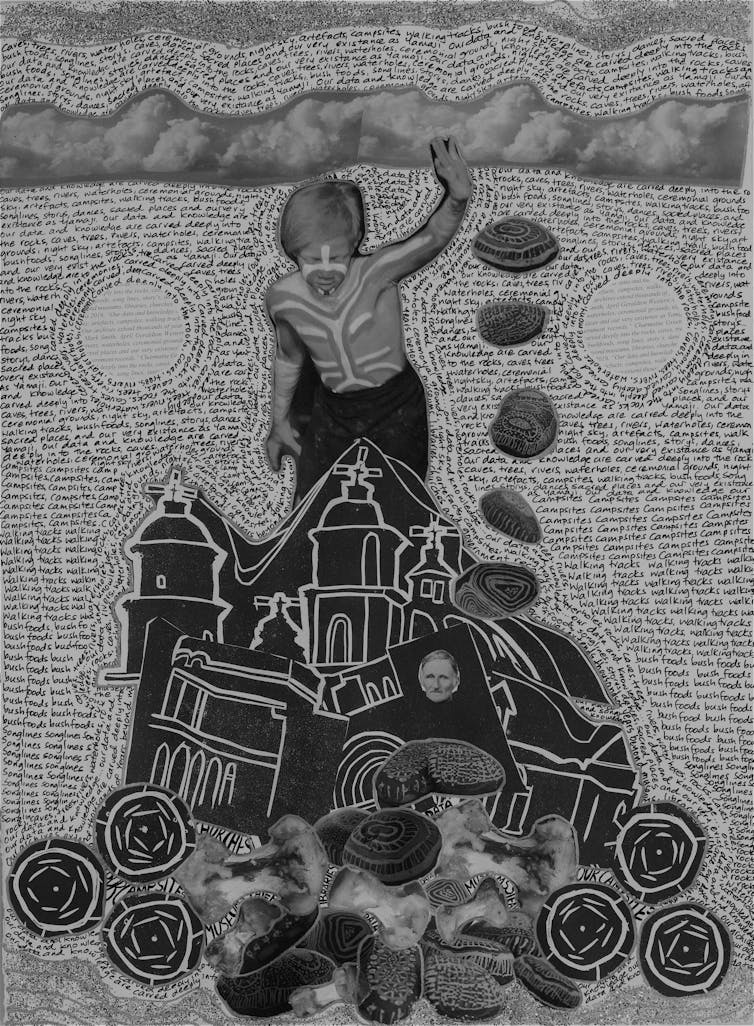

This is my data. And this is my sovereign right.

No more whitewashing. Let Truth be told.

— Data Sovereignty Words

I am a Wajarri, Badimaya and Wilunyu woman from the Yamaji Nation who has grown up on country with family in the small rural inland community of Mullewa, in Western Australia. In this story, I weave together some of my journey through the space of colonial archive violence, silences, and the creation of family stories where there was once a void, filling it with family love.

Love is often defined as an intense feeling of deep affection and a great interest in something and/or someone. We love our Old People, our Ancestors, and we want to know more about them so they can be part of our story and life journeys – this is wrapped in an intense Aboriginal love that is not often recognised. It is an Aboriginal love that takes love even further and is shown when we speak about our love for country, culture, family and Old People.

The Aboriginal love I speak of is when we march, write, sing, weave a basket, create art, return to country often and slowly work through colonial archives, even when it breaks our hearts to do so.

Here, I step into parts of my country that other cultural members might avoid, consider taboo and/or may find somewhat difficult to navigate. This is not easy storytelling, and it rarely is when we speak about trauma, family, violence and colonial archives. But one of the ways we can find family love is by sifting through the colonial archive of violence and trauma.

There are many Yamaji families like mine who grew up on country with their families. But this does not mean that we don’t have stories to tell around the violence and trauma that colonial archives bring to our family kitchen tables.

In every corner of this big land now called Australia, all Aboriginal people have been touched by colonisation in some way or another. There are many stories of colonial violence through the generations – we all have different stories to tell and share.

This is some of my story, my family story and a Yamaji story.

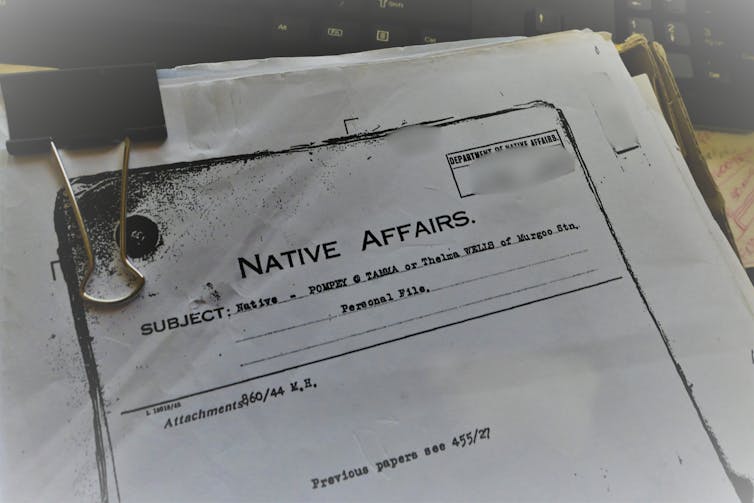

‘Native welfare’ files – Geraldton, WA

I am kin to the colonial archive’s violence

Family stories of removal, genocide and

Social experiments of eugenics and inhumane

Treatments of a First peoples on own country

Nganajungu yungatha needs our medicine

— Yamaji kin songline

Yamaji people cannot access colonial records in Geraldton or Mullewa, because those records are physically stored in Perth archives, 420 kilometres south.

In the past 15 years, I have driven, flown and taken the bus down to Perth in order to access “native welfare” files and any other colonial records. I have searched for any family-related data that I could lay my hands and eyes on. These actions are part of that Aboriginal love of our Old People I spoke to earlier – making time for our Ancestors.

Although I started this journey with family names, dates, place names and family oral history, I still bumped into colonial archive violence and trauma.

On one Perth trip, I was told during a very casual conversation with an Aboriginal History Research Services staff member in East Perth: “perhaps the 1972 Geraldton fire destroyed some of your Old People’s government files?”

The comments were surprisingly offhand and matter of fact, just like crumpling up unwanted paper and throwing it in the waste basket. This response was said in a way that seemed like an excuse if, after searching, there wasn’t any information available.

I really thought how irresponsible and uncaring of the Western Australian government this was. How it devalued the historical data of Yamaji people, by these people who prided themselves on being a culture that wrote down everything with their “civilised” writing system. One could be led to believe that a fire ripped through the Geraldton “native welfare department”, destroying the archives.

In the past, I had heard whispers in the Geraldton community of “native welfare” files being destroyed in a fire. I had heard that a few files survived, taken by Aboriginal staff working in the department at the time, but have never spoken to those Elders. The reality is much more violent, sinister and hurtful for Yamaji people searching for genealogy, truth-telling and family truths.

The truth is that some government “native welfare” bureaucrat ordered deliberate destruction of the archives by burning them in a 44-gallon drum. A junior Aboriginal public servant was instructed to carry out the action at the time, and I am more than grateful that he shared his story publicly so that we know the truth. This is the truth-telling needed.

During my autoethnographic research journey, a newspaper article emerged confirming the Geraldton fire and the deliberate destruction of Yamaji colonial records. All I could think of was the Yamaji children removed and stolen by this violent Western Australian government.

I wondered: did I have some relatives out there that I will never know? And what about those who were stolen and their descendants who may never find their way back home? These are the sad and heartbreaking realities carried by many Yamaji people in their daily lives. But the Aboriginal love deep inside of us, transported across generations, will not allow memories and stories to disappear and vanish.

The Geraldton archival “fire burning” was in the 1970s, an era of “self-determination” and the emergence of Aboriginal rights organisations, land rights and identity pride.

I liken the violent act of deliberately burning paper connections to people, culture and country to cutting an umbilical cord between a mother and child, and then swiftly removing that child. The other thing I want to mention is the way governments and the white man are always trying to cover up the trauma trails inflicted on Yamaji people.

The trauma many Yamaji families face when trying to piece together family history is heartbreaking. Many stories and lived realities have been bravely shared by those taken away and by families diving deep into colonial archives. These stories and journeys help us all learn and understand how Aboriginal culture and its people were violently attacked during colonisation as a form of genocide.

A sliver of information or data can make the world of difference to Yamaji family connection, belonging and identity. And those Yamaji who bravely push through colonial archive pages do so with love and are indeed part of their family line of healers.

Heart-pain sisters

Where? The space is not silent/ never silent/ You can

sit out in the bush/ Insect’s drone, ears ringing/ In the

quietest places and times/ I can hear my breathing/ I can

hear my heartbeat/ People talk about control

— Just Like That

I want to touch on the trauma that comes with silence and being silent. I am referring to the silences we carry that may have been inherited intergenerationally, or the silence that arrives and lingers after tragedy strikes. Or when our Elders pass on. The silences that bring trauma to individuals, families, cultural groups, and a community.

I want to share an experience at a Geraldton event that evoked intense personal feelings connected to these types of silences and heart emotions.

A local Aboriginal poet was doing some public poetry reading and she mentioned her “heart pains” – a pain she described as being connected to not knowing her grandparents and the jealousy she felt when seeing grandmothers with their grandchildren. At that very moment she became my “heart pain” sister, with her words stitching straight into my heart because this was a feeling I knew.

But of course, I never did tell her or share my feelings with her – I didn’t want to bond over trauma in that way. I guess we just continued to carry our invisible “heart pains” in our daily lives. I, too, didn’t know my grandparents, especially my grandmothers, and longed for a granddaughter–grandmother relationship with wisdom, love and caring. But, instead, I was handed some painful silences and both of my grandmothers’ graves to drive past each day at the Geraldton cemetery.

I don’t have a special grandmother recipe to hand on to family, or grandparent stories to share around a campfire with extended family. But what I do have is recipes handed down from my mother – such as kangaroo-tail brawn. Over the years, I did wonder why there were these silences in my family.

What I do understand is that Nanna Alice died 25 years before I was born, and Grandmother Green died when I was 11 years old. This means all their knowledge, stories and information was handed only to those in direct contact with them at the time – their family members, including my parents.

One of the old Yamaji cultural practices I don’t like is when those who have passed are not spoken of again using their names that were used in the living world. I absolutely respect this cultural practice, but I don’t like that family and cultural information could be lost when not talking family names and when cultural knowledge is not forwarded to each generation.

I tried to ask Mum and her brother questions about their mother, Alice Papertalk, who had died young at 42 years of age in Geraldton. Mum whispered some very important stories over the years, but her brother reluctantly shared stories. They both looked so sad when I did ask, and I now understand this was their “heart pain” of losing their mother so young.

These were contributing reasons for the family silence wrapped inside the Yamaji cultural practice of not speaking of those who had passed and then the “heart pain” reasons felt by our parents and their siblings.

The colonial records offer different types of silences and some of the reasons why our families remained silent or were deliberately silenced. I had to work through these silences to bring family stories alive for myself and other family-tree members. I did not get to learn the meanings of these family silences from old Ancestors who had passed before I was born.

But I did get the sad silences from my mum and her brother when they whispered of their Old People. I could read from their body language, their eyes and the lowering of their heads when they did not want to talk to me about something. I had to accept the family silences held something that I needed to find to complete our family stories.

I did find my answers after they had all passed away.

A family silence narrative

It is a real thing, isn’t it, the silences that are carried forward across generations? I often hear other Yamaji say, “I wasn’t told that story” or “No-one told me about them Old People” or “We don’t know our Old People before our grandparents”. We learn over the years that silence talks and can tell us many things if we are patient and learn silence-listening. There was not much talk, family-tree talk, about our maternal great-grandfather: he was mainly referred to as Old Darby; I call him Old Gami Darby.

Therefore, family history and stories about this great-grandfather were not really handed down to my generation beyond knowing his name. There again was an unexplained silence. There was a near erasure of this great-grandfather from our family tree, and I found this quite distressing.

I could not stop thinking over the years why there was a strong “quietness” around this Ancestor. I wanted to know about all my Yamaji Ancestors. This great-grandfather was part of my identity – he is part of my identity. He is my identity. His story and name deserve to be carried forward in the world that colonisation brought to this land. I want to honour him.

It was while delving into colonial archives at the State Records Office of Western Australia in Perth that I learnt of my great-grandfather’s tragic fate. He was murdered – shot dead by another Aboriginal man between Meeberrie Station and Mount Narryer Station in the Murchison. Perhaps, closer to Meeberrie Station.

It was his son, Gami Big Jack Darby (Nanna Alice’s brother) who on 30 December 1917 reported to the Yalgoo Police Station that “he had received information that his father had been murdered by native Sam” (Yalgoo Police Station, 1919). I was quite shocked to find out great-grandfather Old Gami Darby was murdered in the Murchison.

This new family knowledge lifted the veil on the “family silence” handed down generationally – my mother did not talk about this happening to her grandfather. I wondered if she even knew about this sad and tragic information confronting me on the pages of a colonial document. This discovery was quite heavy, smothering me, and I felt I just needed to get out of the State Records Office to breathe and process what I had just read.

Once outside the dark confines of that department, I phoned a cousin to share this additional family information because I didn’t want to hold this type of information by myself. I needed to share it and share it fast because the trauma it brought was not going to be handed down into the next generations in silence. In many ways, this discovery gave answers and reasons as to why stories about Great-grandfather Old Gami Darby were probably not passed down the generations.

My grandmother Alice Darby was a very young mother having her first child when her father was murdered, between Meeberrie Station and Mount Narryer Station. I am not sure if Grandmother Alice went back to Meeberrie Station to live after moving south to the Mullewa area with Pop Ned Papertalk.

Her sister Thumma was buried at Meeberrie, and her mother Angeline worked and lived there, although Grandmother Alice worked and stayed at Woolgorong Outcamp and other stations in the Midwest and Murchison. That Alice died in her early 40s in Geraldton is another significant contributing factor to the lack of family oral history handed down around her father, Old Gami Darby.

My mother told me her maternal grandfather was from the Murchison and lived in the Meeberrie and Mount Narryer station areas and Murchison. His name was Tommy Darby or Old Darby. That was the end of the conversation, but it didn’t satisfy my need to break family silences, or my need to know more.

I wanted to know more information, so I had to search through more records, audio recordings and personal stories of other family members. My mum and all her siblings had passed away by the time I found this information in Perth about his death.

The sad thing is that this silence meant we did not have great-grandfather stories passed down to share with the younger generation. It is because of this I have decided to create a great-grandfather story of this Yamaji male Ancestor in the Murchison. A story I can pass on to other family members, and they can pass to their family members. This story is based on the last day in the life of Old Gami Darby in the Murchison.

The colonial records at least gave me some information and ways to find family love for this Ancestor to enable family silences to be broken and for our family healing tree. I can’t even begin to explain my mixed emotions in doing this, but it’s mainly so that the love for an Old Gami Darby narrative can be built on into the future.

There are some of us who refuse to go into colonial archives, for many reasons. But then there are others, such as me, who delve right in and navigate through the colonial writing, colonial pages and colonial mindsets of another era and a not-so-friendly colonial culture, to try to make sense of the impact of colonisation and to make sense of our family stories in this unforgiving process of colonisation.

I cannot talk about other cultural members’ relationship with colonial archives because it is such a personal private space, and I shouldn’t be expected to do that. My relationship with the colonial archives has been one where I was searching with a purpose for missing pieces to complete family stories and create new family stories.

I wanted to firstly have a look, then claim back my Old People’s stories from those colonial pages. I wanted to pull those words off the pages and tuck them safely away in my notepad and bag to take home. I wanted to imagine and create an Old Gami Darby story based on the colonial court records, police records and the oral history from my mother and her family.

I was anxious reading the court records. There were many thoughts rushing through my head about the Yamaji people with Old Gami Darby in the same camp when he got shot.

Was it an accidental murder or was it something more sinister? What was their relationship to Old Gami Darby and were they afraid to carry the story forward? What exactly did they tell their families and descendants? Far too many thoughts flooded me, but at the end of the day I wanted to honour Old Gami Darby by writing a short story about his last day on this earth and on his country.

I don’t have all the information and am basing the following story on what I do have. Well, it’s more of a reflection and my imagining from documents I have.

The last day of my great-grandfather, Gami Darby

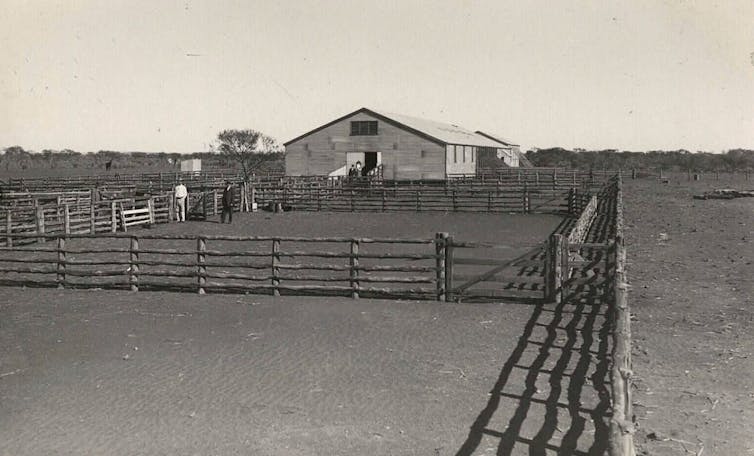

In December, the Murchison in Western Australia is an extremely hot place, with temperatures up in the thirties or more. On 17 December 1917, a group of Yamaji (six adults and one little girl) set up camp on what they called the Meeberrie– Mount Narryer Station run. The Yamajis recorded present were called Mary Jane, Polly, Tommy (our great-grandfather Old Gami Darby), Jinnie, Girlie, Sam and Jinnie’s little girl Annie.

On this day Old Gami Darby was wearing a khaki shirt and blue flannel pants. He also had a piece of a magnifying glass on him, quite possibly to read or look at things close-up. It was a hot morning with no clouds in sight when Old Gami Darby, Jinnie (aka Jubyjub) and little girl Annie went to the creek looking for a tomahawk wood handle. Girlie, Mary Jane and Polly stayed at the camp while Sam went into the bush with his rifle – maybe hunting with his rifle.

At some stage during the day, Girlie, Mary Jane and Polly heard a gunshot thinking it was someone – perhaps Sam – kangaroo shooting. Then they heard and saw Jinnie running back towards the camp screaming, “Someone shot my mardong [man]”. (Meaning Great-grandfather Tommy – Old Gami Darby.)

Jinnie rushed back to the camp looking for something to cover Old Gami Darby, who was shot on the ground. Girlie, Mary Jane and Polly went to have a look at where Old Gami Darby laid deceased on the ground. Sam, who was described as a very tall Yamaji man about six foot, was standing there with his gun and threatening everyone with what would happen if they “told any other blackfellas”. Sam told the group that Great-grandfather Tommy (Old Gami Darby) was struck by lightning.

The Yamaji women told the police there were no clouds in the sky – it was a hot day. Sam made them all help with digging a shallow grave and then burying Great-grandfather Tommy, Old Gami Darby. Sam then took off with Jinnie and the little girl Annie heading towards the Kennedy Ranges in the Gascoyne.

Sam was not convicted for murdering our great-grandfather, Old Gami Darby, because there were no actual eyewitnesses – they only heard the sound of the gunshot. This was our Old Gami Darby’s last day alive in the Murchison. Months later, Pop Big Jack Darby (Nanna Alice’s brother) is recorded by the Yalgoo Police Station as having taken his father Old Gami Darby’s body to the Mount Narryer Station area for reburial at a site unknown.

Old Gami Darby we been waiting for you

To sing your song through the Midwest

And Murchison bush and open sky

Meebeerie and Mount Narryer is no

Stranger even if we live in town

To stare into the campfire in Mullewa

And in Geraldton and send you love

Old Gami Darby we been waiting for youOld Gami Darby I been waiting for you

To share your name and story

— Old Gami Darby

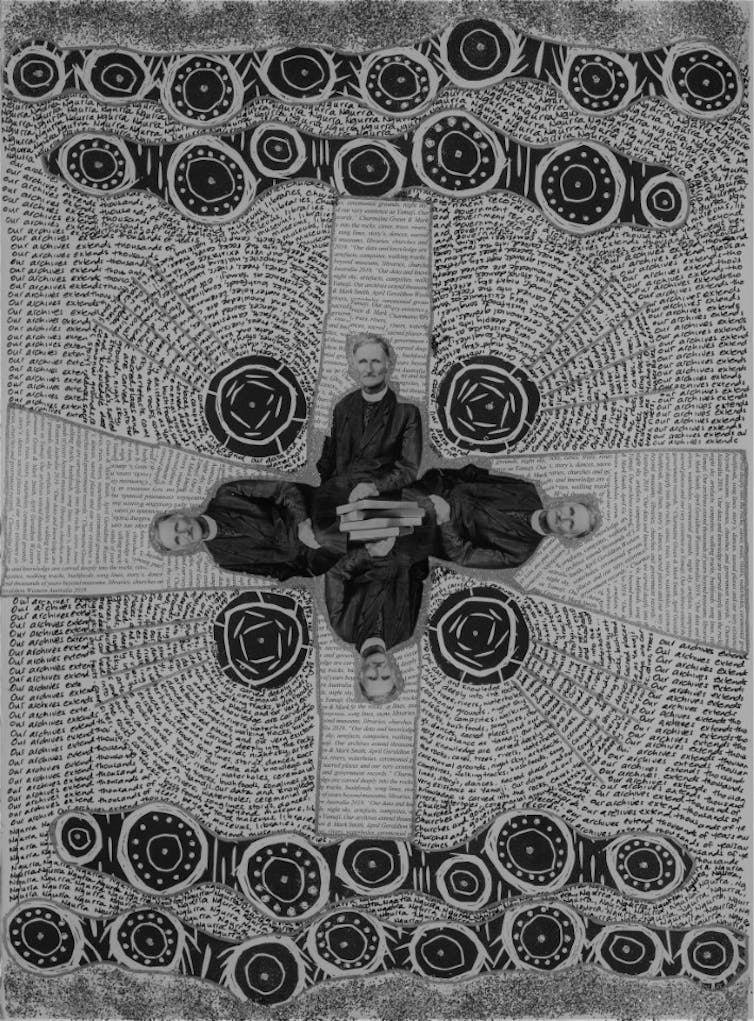

Colonial archives trauma

One of our cultural practices or protocols throughout Australia is to introduce yourself and let people know your cultural groups and family names. It is a custom of positioning yourself in the First Nations world. Letting people know who your relatives are and where your ancestral country is located, your connections.

Colonisation severely disrupted this cultural practice by erasing and disconnecting Yamaji people from place, people and family. In my journey through the colonial archives, native title conversations with anthropologists and others, the presence of alias names caused confusion, frustration and trauma.

This concept of alias names is often found in colonial files with the symbol @ – for example, Alice@Helen. There were arguments over Yamaji with two or more names being in fact the same person, especially when some Yamaji didn’t understand the impact of alias names.

The actions of pastoral station owners, police officers, colonial records administrators and others changed Yamaji identities with the stroke of a pen, most times creating a tangled identity web that was complex to unravel.

These pastoralists, colonists and so forth gave some of my Ancestors different names depending on where they were located (which station they were living at) – they just went ahead and changed their names. The colonials erased and removed traditional names because they couldn’t pronounce or spell the Yamaji names. And all these assimilationist practices were acceptable because Yamaji culture was not valued or considered part of the colonisers’ world.

The community tensions created around identity and connection exist to this day, with other Yamaji confused and not aware of or understanding the impact of name changing on stations or in colonial records.

In the colonial archives, my mother’s maiden name Papertalk was spelt Papidok and Paperdog. My maternal grandmother’s names in the same colonial file were recorded as Alice Darby, Ella Merritt, Alice Papertalk, Alice Marlow, Alice Paperdog and Helen Marlow. Even my family’s younger generation became confused, not understanding the name alias concept.

My maternal grandmother’s sister’s traditional name was Thumma/Tama and yet in her colonial files, depending on which station she was at or partner she had, her names were recorded as Tama Wells, Thelma Wells, Bessie Wells and Bessie Pompey. This grandmother’s sister was buried at Meebeerie Station with the incorrect name Bessie Papertalk – it was her sister Alice (my grandmother) who had married a Papertalk.

All of this data will be corrected out at the Meeberrie cemetery in the Murchison.

I am just a little paper dog

Ready to bite your ankles

And chase you in the vaults

Of truth telling to open your eyes

— Little paper dog

The concept of name alias has caused many arguments and distrust in the local native title process because many Yamajis do not know or understand that Yamaji people’s names were changed and given nicknames and aliases by station owners, native affairs recording clerks and other government officials.

The process of erasure and colonisation meant discarding traditional Yamaji names and replacing them with English names and terms.

Data sovereignty: ‘It is Yamaji data’

The colonial archives were never created for Yamaji people. They were a racist colonial tool to control and manage Yamaji. We understand that the collection of our Old People’s data in this way came from a place outside of Aboriginal love.

Knowing about the how and why hurts in many different ways for different Yamaji families. A lot of times, it is a hurt so deep that our Old People’s stories waiting inside these files remain untouched, hidden and silenced. I only understand that real deep hurt and trauma exists because of stories I have been told from other Yamaji people and some of my own family members.

I came into this journey 20 years ago as an adult, carrying my suitcase of knowledge and experience of what to expect inside the files and on the pages. I needed patience, courage and the ability to work through searching with Aboriginal love. This doesn’t mean I didn’t get angry, feel sad and cry, or just feel so grateful – a range of emotions existed, but I came prepared.

The colonial writing would be hard to read, so translating would take time. The words and terms used were racist, derogatory but expected. This fuelled me with the energy needed to push on through each page of each file. I came to this journey accepting that any data written about my family and Old People was our Yamaji data. This data belonged to us. It was Yamaji data, regardless of who wrote it and what it was written on, and I claimed our data as it is my right.

I had decided to claim any colonial records such as the so-called “native welfare files” as a way to gain insight into the lives and reality of my Old People in times I would not experience and live as a teenager or an adult. This is the relationship I wanted with colonial records. I prepared myself to sift through with Aboriginal love for my Old People.

I was determined these colonial archives would not harm me or my family, but rather bring healing benefits to my Yamaji family tree.

We deserve stories and knowing from the colonial archive perspective to stitch with our Yamaji cultural knowledge. It is our deepest honour to our Yamaji Old People. And while the burning of the files hurt, it didn’t erase our right to our data sovereignty and love our people. I am still thinking about you, my family.

Ngatha Nganajungu yagu Nganggurnmanha

I am still thinking about you my mother

Ngatha Nganajungu mama Nganggurnmanha

My father I am still thinking about you

Ngatha Nganajungu gantharri Nganggurnmanha

I am still thinking about you my older brother

younger brother

Ngatha Nganajungu gami Nganggurnmanha

I am still thinking about you my grandfather

Ngatha Nganajungu Aba Nganggurnmanha

I am still thinking about you my grandmother

Ngatha Nganajungu (family) Nganggurnmanha

I am still thinking about you my family

— Nganajungu Yagu

This essay is an edited extract from Shapeshifting: First Nations Lyric Nonfiction by Jeanine Leane & Ellen van Neerven (UQP).

Charmaine Papertalk Green does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.