Buddhism is the third largest (and fastest growing) religion in Australia with approximately half a million adherents.

The celebration of the Buddha’s birthday here (on or around May 15) has become a major cultural event and the Buddhist doctrine of “mindfulness” is now a part of mainstream culture. But how and when did the West discover the Buddha?

The facts about the Buddha’s life are opaque but we can assume he was born no earlier than 500 BCE and died no later than 400 BCE. He was said to be the son of an Indian king, so distressed by the sight of suffering that he spent years searching for the answer to it, finally attaining enlightenment while sitting under a bodhi (sacred fig) tree.

The Buddha’s family name was Gotama (in the Pali language) or Gautama (in Sanskrit). Although it does not appear in the earliest traditions, his personal name was later said to be Siddhartha, which means “one who has achieved his purpose”. (This name was retrofitted by later believers.)

According to Buddhist tradition, the Buddha spent 45 years teaching the path to enlightenment, gathering followers, and creating the Buddhist monastic community. According to the legend, upon his death at the age of 80, he entered Nirvana.

In India during the 3rd century BCE, the emperor Ashoka first promoted Buddhism. From this time on, it spread south, flourishing in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, then moving through Central Asia including Tibet, and on to China, Korea, and Japan. Ironically, the appeal of Buddhism declined in India in succeeding centuries. It was virtually extinct there by the 13th century.

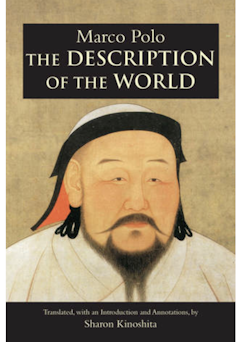

In that same century, the Venetian merchant Marco Polo gave the West its first account of Buddha’s life. Between 1292 and 1295, journeying home from China, Marco Polo arrived in Sri Lanka. There he heard the story of the life of Sergamoni Borcan whom we now know as the Buddha.

Marco wrote about Sergamoni Borcan, a name he had heard at the court of Kublai Khan, in his book The Description of the World. This was the Mongolian name for the Buddha: Sergamoni for Shakyamuni – the sage of the Shakya clan, and Borcan for Buddha – the “divine” one. (He was also known as Bhagavan – the Blessed One, or Lord.)

According to Marco, Sergamoni Borcan was the son of a great king who wished to renounce the world. The king moved Sergamoni into a palace, tempting him with the sensual delights of 30,000 maidens.

But Sergamoni was unmoved in his resolve. When his father allowed him to leave the palace for the first time, he encountered a dead man, and an infirm old man. He returned to the palace frightened and astonished, “saying to himself that he would not remain in this bad world but would go seeking the one who had made it and did not die.”

Sergamoni then left the palace permanently and lived the abstinent life of a celibate recluse. “Certainly,” Marco declared, “had he been Christian, he would have been a great saint with our Lord Jesus Christ”.

Read more: How the Buddha became a Christian saint

Jesuits and authors

Little more was known about the Buddha for the next 300 years in the West. Nevertheless, from the mid-16th century, information accumulated, primarily as a result of the Jesuit missions to Japan and China.

By 1700, it was increasingly assumed by those familiar with the Jesuit missions that the Buddha was the common link in an array of religious practitioners they were encountering.

For example, Louis le Comte (1655-1728), writing his memoir of his travels through China on a mission inspired by the Sun King Louis XIV declared, “all the Indies have been poisoned with his pernicious Doctrine. Those of Siam call them Talapoins, the Tartars call them Lamas or Lama sem, the Japoners Bonzes, and the Chinese Hocham.”

The writings of the English author Daniel Defoe (c.1660-1731) show what the educated English reader might have known of the Buddha in the early 18th century.

In his Dictionary of all Religions (1704), Defoe tells us of an idol of Fe (the Buddha) on an island near the Red Sea, said to represent an atheistic philosopher who lived 500 years before Confucius, that is, around 1,000 BCE.

This idol was carried to China

with Instructions concerning the Worship paid to it, and so introduced a Superstition, that in several things abolish’d the Maxims of Confucius, who always condemned Atheism and idolatry.

Confusion

A quite different Buddha was to be encountered by the British in the later 1700s as they achieved economic, military, and political dominance in India. Initially, the British were reliant on their Hindu informants. They told them the Buddha was an incarnation of their god Vishnu who had come to lead the people astray with false teaching.

More confusion reigned. It was often argued in the West that there were two Buddhas – one whom Hindus believed to be the ninth incarnation of Vishnu (appearing around 1000 BCE), the other (Gautama) appearing around 1000 years later.

And yet more confusion. For there was a tradition in the West since the mid-17th century that the Buddha came from Africa.

Well into the 19th century, it was thought that representations of the Buddha, particularly in India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, depicted with woolly hair and thick “Ethiopian lips” (as one writer put it) were evidence of his African origins.

Such observers were mistaking traditional representations of the Buddha with his hair tightly coiled into tiny cones as a sign of his African origins.

First use of the term ‘Buddhism’

Two major turning points eventually sorted out these confusions. The first was the invention of the term “Buddhism”.

Its first use in English was in 1800 in a translation of a work entitled Lectures on History by Count Constantine de Volney. A politician and orientalist, de Volney coined the term “Buddhism” to identify the pan-Asian religion that he believed was based on a mythical figure called “Buddha”.

Only then did Buddhism begin to emerge from the array of “heathen idolatries” with which it had been identified, becoming identified as a religion, alongside Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

The second turning point was the arrival in the West of Buddhist texts. The decade from 1824 was decisive. For centuries, not a single original document of the Buddhist religion had been accessible to the scholars of Europe.

But in the space of ten years, four complete Buddhist literatures were discovered – in Sanskrit, Tibetan, Mongolian, and Pāli. Collections from Japan and China were to follow.

With the Buddhist texts in front of them, Western scholars were able to determine Buddhism was a tradition that had arisen in India around 400-500 years BCE.

And among these texts was the Lalitavistara (written around the 4th century CE), which contained a biography of the Buddha. For the first time Westerners came to read an account of his life.

The Lalitavistara and other biographies depicted a highly magical and enchanted world – of the Buddha’s heavenly life before his birth, of his conception via an elephant, of his mother’s transparent womb, of his miraculous powers at his birth, of the many miracles he performed, of gods, demons, and water spirits.

But within these enchanted texts, there remained the story of the life of the Buddha with which we are familiar. Of the Indian King Shuddhodana who, fearing Gautama would reject the world, keeps his son sheltered from any sights of suffering. When Gautama finally leaves the palace he encounters an old man, a diseased man, and a dead man. He then decides to search for the answer to suffering.

For the Buddha, the cause of suffering lies in attachment to the things of the world. The path to liberation from it thus lies in the rejection of attachment.

The Buddha’s way to the cessation of attachment was eventually summarised in the Holy Eightfold Path – right views, right resolve, right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right meditation. The outcome of this path was the attainment of Nirvana when the self at the time of death escaped from rebirth and was extinguished like the flame of a candle.

This selfless Buddha, who was said to have died in the groves of trees near the Indian town of Kusinagara, was the one the West soon came to admire. As the Unitarian minister Richard Armstrong, put it in 1870,

his personality has endured for centuries, and is as fresh and beautiful as now when displayed to European eyes, as when Siddharta [sic] himself breathed his dying breath in the shades of (the forest of) Kusinagara.

History versus legend

But is the Buddha of the legend also the Buddha of history? That the tradition we call Buddhism was founded by an Indian sage named Gautama around the 5th century BCE is very likely.

That he preached a middle way to liberation between worldly indulgence and extreme asceticism is highly probable. That he cultivated practices of mindfulness and meditation, which led to peace and serenity, is almost certain.

That said, the earliest Buddhist traditions showed little interest in the details of the life of the Buddha. It was, after all, his teachings – the Dharma as Buddhists call it – rather than his person that mattered.

But we can discern a growing interest in the life of the Buddha from the first century BCE until the second or third centuries of the common era as the Buddha transitions within Buddhism from a teacher to a saviour, from human to divine.

It was from the first to the fifth centuries CE that there developed a number of Buddhist texts giving full accounts of the life of the Buddha, from his birth (and before) to his renunciation of the world, his enlightenment, his teachings, and finally to his death.

Thus, there is a long period of at least 500-900 years between the death of the Buddha and these biographies of him. Can we rely upon these very late lives of the Buddha for accurate information about the events of his life? Probably not.

Nevertheless, the legend of his life and teachings still provide an answer to the meaning of human life for some 500 million followers in the modern world.

Philip C. Almond does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.