Sexual politics is difficult terrain for young people to navigate. Desire, threat and insecurity are a powerful combination in the most benign circumstances, even before teenagers were drenched in social media harassment and ubiquitous porn.

Outside the privileged cloister where we tested the limits, my generation of assertive young women were surprised to realise we represented a visceral threat to those men who chose to remain unmoved by the new politics that took the personal seriously.

The chilling reality of this confronted me not long after I arrived in Cairns in 1975, on the first leg of my journey to interview the bush poets scribbling away in Far North Queensland.

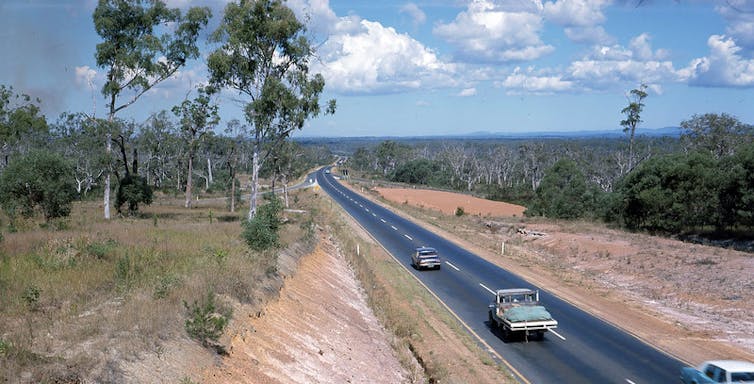

As I stood waiting for my brand new suitcase to appear on the baggage trolley towed from the plane, I fell into easy banter with a cowboy from central casting. He didn’t offer to carry my luggage but followed me to the hire car desk. His insistent attention put me on alert. I brushed him off, then made my way to the car park and onto the highway to town. Phew.

The threat had felt real. I had absorbed the reports of the Bruce Highway horror stretch a little further south. Six unsolved murders in six years, and another two just months earlier. I locked all the doors of the little Mazda, wound the windows up tight, and kept an eye on the rear-vision mirror until I pulled into the motel, checked into my room and drew the curtains.

Then the cowboy’s harassment really started. First a phone call, then a knock on the door, angry pacing outside the room, another call and banging on the window. I rang reception to complain and was told to get over it. No one was sent up the stairs to tell him to get lost or that they would call the police.

The message was clear: women were fair game. It seemed like hours before he gave up. I was exhausted. In the morning, I gobbled the cardboard cereal and white toast pushed through the breakfast hatch, drank the pot of Robur tea, paid the bill and dashed to the car park. Then I locked myself in the car.

I was a bundle of nervous energy. It scarcely dissipated on the hour-long journey through the stifling heat of the pre–wet season, down the palm-fringed tropical coast to Innisfail. I was too afraid to stop, though I desperately wanted to have a swim, even in crocodile- and stinger-infested waters. I worried that if I did, the angry cowboy – or some of his mates – might reappear. I had read enough newspaper reports to know that young women disappeared on remote country roads.

There was nothing exceptional about my experience. Everyone I knew had a similar story, or worse. The legacy of a violent frontier could not be wished away and did not just evaporate. It echoed through the generations, finding new targets. Modern Queensland was still pumped up with the testosterone-fuelled aggression that had marked its founding.

After I returned from my road trip, a friend told me she had seen brutal violence against women in some towns in Far North Queensland – assaults that were organised and condoned, the perpetrators beyond the reach of the law.

It was, we would now say, structural. Not just a few bad eggs, but a system that treated young women as chattels. In her town, not far from my uncomfortable experience, gangs of men and boys routinely identified a female target at a public event and enticed her outside. They called the gang rape a “train” and convinced themselves, and the police, that the woman was “asking for it”. The traumatised victims were rarely believed, the legal system seemingly designed to humiliate, shame and silence them.

When we helped journalists from the National Times with the research they needed to travel to the town and report what was going on, an ancient mechanism of control in new garb was fully revealed.

Within no time at all, similar stories bubbled up out of other country towns. After the horror of these organised attacks was reported, the campaign to ensure that the victims of sexual assault were treated with respect in Queensland gained new momentum. One of the only two women in the state parliament made it an issue.

Rosemary Kyburz was a Liberal MP who would do all she could to ensure these assaults did not go unpunished. Within a couple of years, the law changed a little.

Inquiries, reports, submissions and debates followed, and changes continued to be made for decades as the legacy of embedded misogyny revealed itself over and over. Sexual abuse could no longer be dismissed with the mocking laugh that had once accompanied it.

Nevertheless, nearly 50 years on, the law still works against female victims. The suppressed anger that many women carry burst to the surface of public life when another generation of young women, led by Grace Tame, Brittany Higgins and Chanel Contos, declared Enough is enough.

A few weeks after International Women’s Day 2021, in cities and towns around Australia, women and men, many who hadn’t marched for decades, took to the streets in response to the revelations of sexual abuse in Parliament House. The echo of past protests reverberated around the nation. It had not taken long for the 800,000 women who had been added to the electoral roll in 1903 to become a wellspring of conservative votes for decades, but the polls suggested they would be no longer.

A right, not a gift

The animating idea of the women’s movement – that equality was a right, not a gift or a political deal – transformed interpersonal relations, and crept into workplaces and schools. Language changed, expectations were recalibrated, and before long, behaviour followed. But it did not happen overnight and did not happen without a struggle. The ban on married women working in the public service had been lifted only two years before I started high school.

At that time, women were still the exception in the professions, paid one-third less than men and denied access to superannuation. In 1973, a few million dollars was made available by the federal government for the first time to support childcare and some support for women’s refuges followed. It was tiny by today’s standards but it transformed lives.

Four years later, the editor of the Courier-Mail drew my first serious job interview to a halt: “What it is with you girls, why do you all want to be journalists, what’s wrong with teaching and nursing?” I didn’t bother to turn up for the second interview after the editor of the Gold Coast Bulletin, which still featured women in bikinis on the front page, said, “If you’re a pretty girl, come on down; if not, don’t bother.”

Soon the patter became more sophisticated. As Max Walsh, the editor at the Australian Financial Review, had told me at my job interview – in a pub – women would work twice as hard for half the money as men, and he thought they’d be more able to extract secrets from businessmen than male journalists.

A few years later, in the early 1980s, when I was armed with a clipping-book full of front-page stories and some experience in television, the head of current affairs at ABC TV baited me for an hour before dismissing me, asking, “What makes you think you are pretty enough to be on television?” Belittling and shaming were still ready tools of choice to put women in their place.

The year before my experience at the ABC’s Gore Hill headquarters, the High Court had ruled that Ansett Airlines could not discriminate against a woman who was otherwise qualified to be a pilot. I had reported on Deborah Wardley’s case for years as her prospective employer invented one excuse after another to block her – women weren’t strong enough; unions would object; menstrual cycles, pregnancy and childbirth would jeopardise safety and increase costs. The court ruled on technicalities, not on principle.

When a group of older mentors urged me to make a complaint about my treatment at the ABC, the cost seemed higher than any possible reward. I kept my notes and moved on; revenge, as they say, is a dish best served cold.

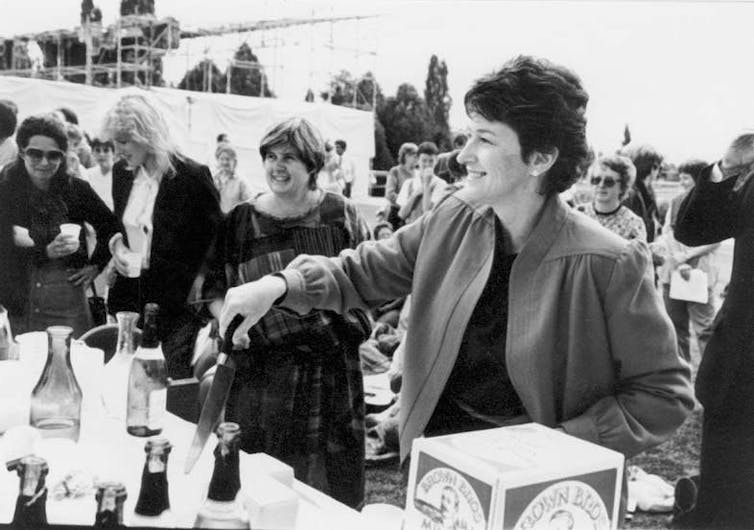

It took until 1983 for Australia to sign the 1979 United Nations convention designed to eliminate all forms of discrimination against women. Legislation followed in 1984, but its principal proponent, the Labor senator Susan Ryan, was subjected to bitter personal and public attacks.

At the big rallies in Canberra, anxious and angry Women Who Want to be Women pushed to the front to protest the changes. Some 80,000 people signed petitions opposing the relatively modest sex discrimination bill. Although key Liberal leaders supported it, the right wing of the party was bitterly opposed. It marked the beginning of a split that would dog the party for decades.

Read more: Friday essay: Sex, power and anger — a history of feminist protests in Australia

Susan Ryan was a feisty campaigner, so the vicious onslaughts only increased her resolve. Women’s rights were on the way to becoming human rights, talent was no longer sifted by sex, but the extent of the opposition stunned her.

The Australian legislation passed with the support of some Liberal members of parliament who defied their party and crossed the floor to vote with the government.

Women did not have a secure footing in the dominant political party, as deputy Liberal leader and foreign minister Julie Bishop and Liberal MP Julia Banks found in the internal party confrontation that ousted Malcolm Turnbull and replaced him with Scott Morrison. As Julia Banks declared in the House of Representatives, as she prepared to leave in 2018,

Often when good women call out or are subjected to bad behaviours, the reprisals, backlash and commentary portrays them as the bad ones: the liar, the troublemaker, the emotionally unstable or weak, or someone who should be silenced.

“Tell us the story again about the newspaper job interview in the pub,” my teenaged daughter and her friends would say, at the turn of the century, each time we drove down Broadway past the old Fairfax building towards Sydney University. “Can you believe it?” the girls would chuckle.

Then they too entered the workforce and realised that the more subtle but deadening hand of sexual discrimination was still doing its evil work, now hidden behind laws and lofty rhetoric. Change rarely proceeds in a linear manner, but the trend was clear.

Read more: The 'madness' of Julia Banks — why narratives about 'hysterical' women are so toxic

Assertive women, brutal political attacks

When Wayne Goss appointed Canadian-born Leneen Forde as Queensland’s governor in 1992, she was only the second woman governor in Australian history. She had fallen in love with the son of former Australian prime minister Frank Forde and, like countless young brides, moved to Australia full of hope and expectation. She was shocked by what she discovered. Brisbane in the mid-1950s was a poor country town. The appliances she had taken for granted were considered luxury mod cons. A woman’s place was in the home. But when her husband died 11 years later, this was no longer an option for her.

With five young children to support, she began studying law and five years after her husband’s death started work as a solicitor, eventually becoming the queen’s representative in a state named for another.

Queensland, despite the gender of its name, was a place where men prevailed and women were meant to know their place. Matt Foley challenged this when, as the state’s attorney-general, he decided that merit, not gender, would determine judicial appointments.

My former English teacher, Roslyn Atkinson, by then a distinguished barrister who had been the inaugural president of the Queensland Anti-Discrimination Tribunal and deputy chair of the state’s Law Reform Commission, despite outraged protests from the old guard, became one of Foley’s first Supreme Court appointments in 1998.

Within a few years, despite bitter heckling from those who were still convinced that “merit” meant “men”, seven of the state’s 24 Supreme Court judges were women, and a woman was president of the Queensland Court of Appeal. Years later it was still driving the press mad. The Courier-Mail would roll out articles anonymously reporting lawyers who knew women were just not up to it. These eminently well-qualified women were derided as “Matt’s Girls”.

In September 2015, Justice Catherine Holmes became the state’s first female chief justice. This was a change that would not easily slide back. The reaction to these newly assertive women was no less brutal in politics.

When Labor’s Anna Bligh became the first popularly elected female premier in Australia in 2009, the misogyny that later blighted Julia Gillard’s prime ministership had an off-Broadway tryout in Brisbane. Bligh’s resolute leadership during the 2011 floods, like Gillard’s ability to navigate a hung parliament, counted for little. Her determination to privatise ports, roads, trains and coal terminals was not welcomed by traditional Labor voters. Union-sponsored billboards on major thoroughfares mocked her, the press despised her, and a vicious whispering campaign prevailed.

The 2012 election was a disaster for Labor: the party went from holding 51 seats to seven. Electoral tides in Queensland are often more dramatic than normal swings on the carefully calibrated Australian electoral pendulum. It was a relatively short-lived win for the blokes who had felt they were born to run the state. It lasted just one term.

A female perspective

In 2020, the victorious Annastacia Palaszczuk became the first woman to be re-elected premier for a third time. Under her administration, women occupied an unprecedented number of positions of power in what was once the most macho state. It was a long way from the 1970s.

In 2021, most of the ministers in her cabinet were women, as were the governor, chief justice, police commissioner, chief medical officer, head of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, and six of the state’s seven university vice-chancellors.

Second-wave feminists had sometimes wondered, in the abstract, what would happen as occupations were dominated by women. Would that mean the profession had lost status? Was equality realised when mediocre women exercised as much achieved power as mediocre men had always done?

But as Palaszczuk’s legislation to introduce a Queensland bill of rights, legalise abortion, outlaw coercive control, enable voluntary euthanasia and better define consent laws showed in a few short years, a female perspective could change the agenda.

And it could drive some men mad. This was a profound cultural and political change that had nothing to do with detachment from the “mother country”.

Read more: Friday essay: Our utopia ... careful what you wish for

Fault lines

Race and gender discrimination are inextricably linked and have long been defining Australian fault lines. Female convicts – “whores”, in the view of some commanders and male prisoners – were outnumbered at least three to one and were shared among the men in what Anne Summers has described as “imposed sexual slavery”. But many were fiercely independent battlers who wanted a better life for themselves and their children and were prepared to challenge authority.

Similarly, the Cammeraygal woman Barangaroo, who became Bennelong’s wife after her first husband died from smallpox, set the bar high. She was an independent woman, a fierce hunter and provider who saw little reason to compromise with the new arrivals. She once famously attended an official dinner at Government House in traditional garb, her naked body painted in white clay, a bone through her nose.

She died in 1790, so was spared the distress of witnessing the brutal and demeaning treatment of her sisters and generations of others as the fight over the bodies of Aboriginal women became a recurring metaphor of settlement. Some formed loving relationships with settlers, others became leaders, but many were treated as chattels, emotionally destroyed as their children were taken away, their men emasculated.

Australia was and is a deeply male society. For those with enough determination and a strong sense of self-worth, frontier life encouraged a certain female fearlessness that is still evident.

It is clear in the stars that shine abroad: writers and thinkers like Germaine Greer, Geraldine Brooks, Anne Summers and Kate Manne; scientists like the Nobel-winning Elizabeth Blackburn; actors like Cate Blanchett, Nicole Kidman, Rachel Griffiths and Margot Robbie, who luminously fill the world’s screens; educators including Jill Ker Conway and Patricia Davidson; and anthropologists Genevieve Bell and Marcia Langton.

Ever since pastoralists recruited single men, not wanting to be encumbered by the additional expense of providing for families, the political economy of Australia has been built on the primacy of male labour, male power and male control. The native-born and immigrant populations grew in the 19th century, but it took the deaths of more than 60,000 men in the first world war for women to become the majority, although the generational loss reverberated for decades.

Women remained, in Anne Summers’ famous phrase, either “damned whores or God’s police”. Sexualised taunting was and still is the bedrock of abuse likely to rain down on Australian women who speak their mind, provide professional advice, demand more and expect R.E.S.P.E.C.T., as Aretha Franklin sang. Still, nothing fires up the angry Twitterati quite like women making otherwise unremarkable comments about their rights and expectations.

‘One of the most racist towns in the country’

The intersection of these discriminations was on proud, unapologetic display when, in 1977, I flew three hours west of Brisbane to Cunnamulla.

Peter Manning, then the editor of Nation Review, had commissioned me to report on a community that had been characterised as one of the most racist towns in the country for the independent newspaper. As I had learned from my weeks on the road talking to bush poets, travelling alone on this assignment would have been foolhardy, so I accompanied two of my friends. Wayne Goss and Matt Foley were working for the Aboriginal Legal Service at the time, and they had a slate full of meetings and court hearings.

At the time, Cunnamulla was home to 1500 people (about, according to the signpost), seven pubs and seven draperies, and unemployment was officially running at 25%. Eight of every ten Aboriginal people were without work. It was a town where grog ruled, dozens of children were malnourished, and the grief from scores of infant deaths each year was overwhelming.

As the plane touched down, the local man sitting next to me asked where I was staying. The Club, I said. He spoke in the leering, patronising way I had come to expect in my travels through the state, setting the tone for the following week. As we left the plane he reassured me that I would be safe: “They don’t let the darkies into the Club Hotel.”

Cunnamulla is one of a handful of outback Australian towns that has a grim, larger-than-life reputation. Wilcannia, in the far west of New South Wales, which briefly won national attention during the pandemic, is another. Both towns had had their reputations unfairly tarnished, as the requests of their leaders were persistently ignored and dismissed. It has long been easy to ignore those who live beyond the Great Dividing Range.

Not long after William Landsborough described the potential of the land he observed around what became Cunnamulla – as he crossed the continent from north to south in search of the ill-fated explorers Burke and Wills – the south-west of Queensland was rapidly divided into vast stations.

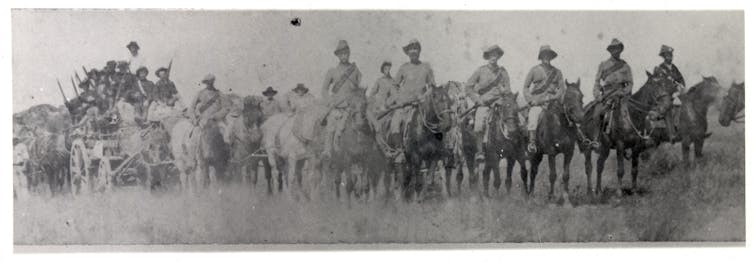

Squatters soon claimed the mulga-clad countryside and murderous incursions became the norm. Native Police were stationed in the Cunnamulla township. Reports of the killings in the 1860s were so shocking that they provoked the Anglican bishop of Sydney to establish a mission. He had been outraged by a squatter’s jape that if he had “known how useful they might be he wouldn’t have killed so many blackfellows”.

Read more: How unearthing Queensland's 'native police' camps gives us a window onto colonial violence

The unprepossessing settlement on the banks of the Warrego River about 800 kilometres due west of Brisbane is an unlikely entry in the compendium of noteworthy places. Its murderous history was conveniently forgotten and replaced with a pastoral fantasy. Maybe the mouth-pleasing ring of the name helped. Henry Lawson thought it suggested pumpkin pies. He immortalised the Cobb & Co. coach stop in his story The Hypnotised Township, but described the town as a place of “troubled slumbers”.

Years later the Aboriginal poet Herb Wharton, who was born near Cunnamulla, won international acclaim when he broke the hypnotic silence. He turned the settler stories on their heads and told the droving tales of Murri stockmen and women. He and his sister Hazel McKellar then recorded the tales of massacres, including the one their grandmother had survived.

Still, the “Cunnamulla Fella”, who lived on damper and wallaby stew and was conjured by country singer Slim Dusty, is the figure who endures as a statue in the town. A selfie with the “Fella” is a tick on the roaming grey-nomad bucket list.

An ugly reality

Dark histories haunt places and often recur in other uncanny manifestations. Some may consider the Cunnamulla Fella a charming artefact of a bygone age, but there was nothing charming about Out of Sight, Out of Mind, the depiction of the town by ABC’s Four Corners program in 1969.

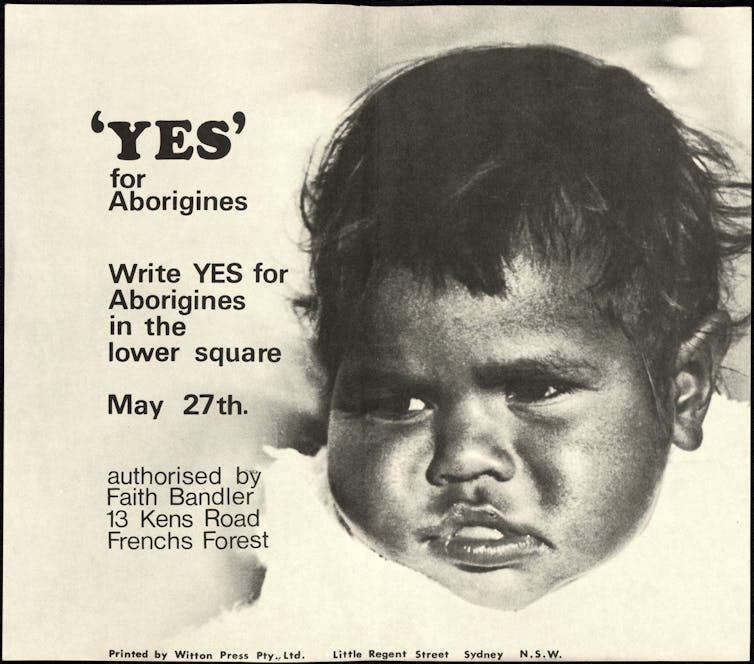

This film, broadcast just two years after the referendum that brought First Nations people into the mainstream, was one of those moments when current affairs television excelled. It brought the shameful reality of life in fringe camps into middle-class loungerooms.

The pale, well-spoken journalist was doing a good job, but looked like a creature from another planet, dropped in to share his outrage. It was an excoriating portrayal of the wrongful conviction of an Aboriginal woman, and of the shocking conditions in the two town camps that were home to descendants of the Kunja people who had once been shot and poisoned by graziers.

Audiences around the country reacted with fury. “I’m praying for [mayor] Jack Tonkin’s soul in purgatory,” one wrote, “but I don’t like my chances.” ABC management prohibited the sale of the program to the BBC; the picture it painted was too ugly for international consumption.

The broadcast prompted an immediate political response: money suddenly became available to build 26 fibro houses scattered through the town. When I visited eight years later, the houses were built and only the remnants of the camps remained. The community links that had given life in the settlement its own coherence had dissipated; drunkenness had become the destructive norm.

The angry racism that once fuelled the frontier wars still had full-throated voice. Like so many outback towns, Cunnamulla seemed to be dying. “You have to blame it on something, what better than the boongs,” one angry newcomer told me.

Those I met on that short trip felt no need to hide their fury. The media had destroyed their town. “We were doing the right thing by the blacks until Four Corners came along,” one self-appointed spokesman berated me when I attended a dinner organised by the Rotary Club.

‘I just want a fair go for the white fella’

The anger in the room bubbled up as they listened to social worker Matt Foley’s talk. When it came time for questions, the local solicitor chairing the meeting passed around handwritten notes: “tone it down”, “no aggressive questions”, “calm down”. The back and forth continued until well after midnight. Then, like a storm that had passed, the tone changed. “We’re still friends, aren’t we?” the man who had most aggressively blamed the media at the start of the evening asked as he wandered off to his car. He should not have been driving.

In the morning a taxi driver who had been part of the angry group the night before nearly ran me over and then demanded I get into his car for a tour of the camps and the new houses. He knew who to blame. As we drove along the uncurbed streets he pointed to one rundown house after another:

Black house, white house, black house … I hope you are going to give those bastards heaps … I just want a fair go for the white fella.

In the previous six months there had been nearly 300 convictions for drunkenness: 163 Aboriginal men and 58 women; 55 white men and two women. “You can’t live here without drinking,” my not-so-friendly taxi driver declared.

Four of the women I met stood out and have remained with me ever since. One was the doctor’s elderly receptionist. When I knocked, she answered the door to the surgery armed with a paper knife. “You learn to expect anything, and prepare yourself,” she said as she put the blade in a drawer.

Another was a tough, damaged woman who owned one of the three pubs that served Aboriginal people. She had installed a metal cage along the bar. “I don’t know why the blacks drink here. I like them, but I’ve lost control. I don’t care how much I lose, I’m selling this place,” she told me.

Outside her pub a young woman, who looked at least 20 years older than she was, grabbed my arm and repeated, over and over,

I’m just a black mongrel bastard. I got no one, I got nowhere to go, I’m just a black mongrel bastard.

Read more: Non-Indigenous Australians shouldn't fear a First Nations Voice to Parliament

Hazel McKellar’s reforming energy

The most outstanding person in the town was Hazel McKellar. She was the antithesis of what Bernard Smith would later describe as the “tragic muse” of Australian arts, the “old Aboriginal woman surviving precariously as a fringe dweller in some unknown country town”. She was a handsome, intelligent woman who, since returning to Cunnamulla after working as a housemaid on stations, had devoted herself to holding her community together as external and internal forces conspired to pull it apart.

Even in progressive circles, the prevailing image of Aboriginal people in the late 1970s was as victims – people with little agency or authority, people who had been damaged or destroyed.

Hazel McKellar did not fit this stereotype. She had big ideas and was prepared to pull whatever levers she could to realise them. She wanted a different school curriculum so children could learn about their culture, something the local school’s principal thought “might be helpful for slow learners”.

Two-thirds of the 440 students at the primary school were Aboriginal, but the experience of their forebears was not evident in the curriculum. In Year 5 social studies, as the principal helpfully explained, “We teach the kiddies about explorers and the opening up of Australia.”

Hazel McKellar’s advocacy for including cultural knowledge was ahead of the zeitgeist. Within a few years she was writing books that captured this knowledge. Her brother Herb Wharton had put the old brigade on notice through his poetry, which they celebrated; they may not have liked what he said, but they understood his language.

During those intense few days in 1977, Hazel and I talked about the immediate past, but not the longer past that had shaped it. Her focus was on the future. She campaigned relentlessly for improvements to health, housing and education, and for a cultural and community centre.

“It’s the little things that niggle, like knowing there is only one white family in town whose kids will come to an Aboriginal kid’s party,” she told me.

I’ve just learnt to not go where I am not wanted. It used to make me angry, and I still resent it at times, but you have to accept it, I guess. But it’s only us who are keeping this place going.

‘Settled in the Dreamtime’

By 2019, the map of south-west Queensland was closer to what it would have looked like about 170 years earlier, when Thomas Mitchell had swept through the region identifying land suitable for cattle. The aerial view of the region from the National Native Title Tribunal’s map now shows a vast patchwork of native title lands, and many places of significant cultural heritage. To the west and south of Cunnamulla, 200,000 square kilometres of land has been returned to traditional owners.

When Hazel McKellar told me in 1977 that it was only her people who would keep the area going, neither of us could have anticipated this transformation. By 2021, the sign at the entrance declared Cunnamulla a “Heritage Town”, “Settled in the Dreamtime”.

The ancient stories of the land and its people, once a cause of such embarrassment and shame, had become a source of pride and inspiration. Anonymous trolls may rage on Twitter, but no one would say out loud the things that they had once said to me, notebook in hand, spellchecking names as I jotted down their comments.

Alexis Wright is a Waanyi woman who grew up in Cloncurry, more than 1000 kilometres north-west of Cunnamulla, at the other end of the Channel Country that regulates the cycles of life in the vast inland. It is the town where Scott Morrison tramped through the cemetery looking for his great-great-aunt Dame Mary Gilmore’s graveyard.

In 2007, Wright became the second First Nations writer to win the Miles Franklin Literary Award for her magisterial novel Carpentaria, then won the Queensland Premier’s Literary Award for fiction – the first Aboriginal author to do so. It was recognition that would have been inconceivable 30 years earlier.

The celebration of her remarkable book was, inevitably, tinged by politics. On the eve of her win in June 2007, the Howard government launched its Northern Territory Intervention, when troops and public servants were sent into remote First Nations communities. The softly spoken author was asked about the intervention and replied with passionate denunciation: there were real problems of abuse in some communities, but a unilateral intervention without consultation could not be the solution.

Read more: Ten years on, it's time we learned the lessons from the failed Northern Territory Intervention

The gestation of Carpentaria had taken many years, as Wright had tried to bring to the page the stories and ways of being she had heard from the old people. Every major publisher rejected the opus before Ivor Indyk at Giramondo Press recognised the novel’s unique brilliance.

In an astonishingly original way, Wright tells hitherto invisible stories and captures the spirit of a different way of storytelling. Her stories wove back on themselves, rich with magic, symbolism, grit and determination; they turned time and place and the conventions of English literature inside out and made her a contender for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The profound change embodied in the accolades she continues to receive, and the insights she shares about the idea of Australia, have very little to do with anxiety about detachment from Britain. Her novels, like many others, better answer the question Who are we? than any politician has for decades. As has happened before and will happen again, by making the political personal and turning it into culture, Wright encourages a new, fit-for-purpose understanding to emerge.

Culture changes

In 1890, another Queensland novelist, Arthur Vogan, wrote The Black Police about the massacres in the state’s Channel Country and his shocked reactions to the way they were applauded by settlers.

It was a surprising popular success. Although local newspapers bristled with reports of deaths from incursions, it was a contentious subject, and one that made for a challenging novel. The critics were scathing, but it struck a nerve and was reprinted several times.

Arthur Vogan lost his job as a journalist, just as Carl Feilberg had done a decade before following his campaign against the Native Police in The Queenslander. Like Feilberg, Vogan also realised he was on a blacklist and had to leave. He moved as far away as he could—to Perth—and gave up writing for some time.

He was one of many authors punished for writing an “anti-Australian” novel. This was a smear that would be spread thickly for decades.

In 1947, Ruth Park was subjected to an organised campaign of threats and vilification for the life she portrayed in Surry Hills in The Harp in the South, which had won a competition run by the Sydney Morning Herald. Subscription cancellations and letters poured in to the editor, all asking different versions of the same question: “Why should Australia, with all her beauty to choose from, have to go to the sewer for her literature?”

Ruth Park also retreated. She left the country amid a chorus of criticism and only returned years later. Now her novels are on school reading lists, Wikipedia lists the dozens of prizes she won, and in 2006 she was recognised in The Bulletin’s list of the hundred most influential Australians. Culture changes, and as it does, once unpalatable truths can be said out loud and challenge and correct ill-informed angry outbursts.

This is an edited extract from The Idea of Australia by Julianne Schultz (Allen & Unwin)

Julianne Schultz will talk about The Idea of Australia, in conversation with Peter Mares, at ACMI on Friday 11 March at 6pm. Free, bookings required. The event will be livestreamed online via ACMI’s YouTube channel. She will also be speaking at various events

Julianne Schultz AM, FAHA does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.