1950s Melbourne hosted an exciting bohemian scene, one that championed unconventional thinking. Within that community there was a general disregard for social norms and traditions. This artistic counterculture, full of intellectual freethinkers and early feminists, was particular to Melbourne, and can be seen in the various places where artistic and literary types thrived.

My parents, Leonard (Len) French and Helen French (née Bald), were swept up in Melbourne’s bohemia during the first flush of their relationship. Both were at the beginning of their careers; he was an aspiring artist and she a fledgling fashion designer.

The Melbourne of their twenties lives on in my imagination through their stories of gathering at the Swanston Family Hotel, frequenting the new city cafes, going to parties in photographers’ studios in Collins Street, watching foreign films at the Savoy, and discovering wonderful secondhand bookstalls in the area around the Flagstaff Gardens.

They would remember mid-century Melbourne as incredibly exciting, full of possibilities, and I have come to think of this period that way as well. The heart of any city is the places that are significant to the people within it.

Finding a tribe

The Swanston Family Hotel is where my father found his tribe. Len went there for a decade from the age of 17. The hotel was on the north-west corner of Swanston and Little Bourke streets, at 233 Swanston Street. A photograph taken in 1911 shows it as a three-storey building flanked by a tearoom and leather workshop, with a private entrance in Little Bourke Street.

The hotel was a favoured haunt for radicals, intellectuals and artistic types for over three decades – from the 1920s to when it was knocked down in 1959.

The pub’s reputation for being a home for alternative culture is upheld by its patrons’ comments – most of whom, my father included, referred to it simply as “The Swanston Family”. Perhaps that said something about the community they found there, where they bantered with peers about art, life, politics and ideas.

It was the closest thing local artists had to a communal hub. My father was drawn to it; he developed quite a reputation as a raconteur, holding court with all who’d listen. This often caused him to be late, much to the chagrin of my mother who spent many cold and uncomfortable hours waiting for him in front of the Melbourne Town Hall, only to have to rush off in high heels to a party or event, sometimes miles away.

My father described the Swanston Family to biographer Reg MacDonald as the antipodean version of cafe society. The other pub favoured by bohemian artists and intellectuals was The Mitre Tavern at 5–9 Bank Place. The Mitre was modelled after an English pub. Built in 1867 it is one of the city’s oldest buildings. When the Swanston Family closed, many of its patrons moved on to The Mitre, which is still there today.

In filmmaker Tim Burstall’s memoir he notes that women, Germaine Greer among them, frequented the Swanston Family Hotel, which would have been illegal at the time. This unusual situation was also mentioned in a conversation between broadcaster and journalist Phillip Adams and author Alex Ettling.

Ettling recalled that artist Noel Counihan, who was at the National Gallery of Victoria’s art school in the 1930s, had made special arrangements with the hotel to bring in female friends and run up a tab. Given accounts of women in the public bar in the 1950s, that practice appears to have continued. It’s most likely there weren’t enough women to attract police attention (mind you, my mother described the hotel as men only).

Many of the regulars at the Swanston Family were workers in the city – journalists or academics from Melbourne University, and artists from the Working Men’s College (renamed Royal Melbourne Technical College in 1954, and RMIT University in 1992), where my father went. Initially he had been an apprentice sign-writer, then one day – while at RMIT for sign-writing classes – he dropped his drawings on the stairs at the exact moment the head of art, Victor Greenhalgh, descended.

As my father’s story goes, Greenhalgh helped him pick the drawings up and, impressed, invited Len to join his art class. Len replied that he’d like nothing better but couldn’t afford it. Greenhalgh offered him a free place and soon Len was going to art classes every night. Whether this was serendipitous, or contrived, we will never know.

Len went on to teach typographical design and lithography for two years from 1955. His successful career as an artist is history. Although he regarded himself as a painter, and wanted to be remembered as such, he is most well-known for the spectacular ceiling of the Great Hall at the National Gallery of Victoria: the largest glass ceiling in the world.

My father’s alma mater became my own, where I achieved my PhD and, like him, went on to teach. I think of this sometimes while walking along RMIT’s Bowen Lane, or approaching Building Six, where the art school has long resided. What kind of a teacher was he? Was he patient with students like he always was when teaching me?

In 1957, aged only 29, Len French became the exhibition officer at the National Gallery of Victoria and was able to influence the direction of its collections. He continued drinking at the Swanston Family until it closed in 1959, resigning from the gallery the next year in 1960.

Cultural mavericks

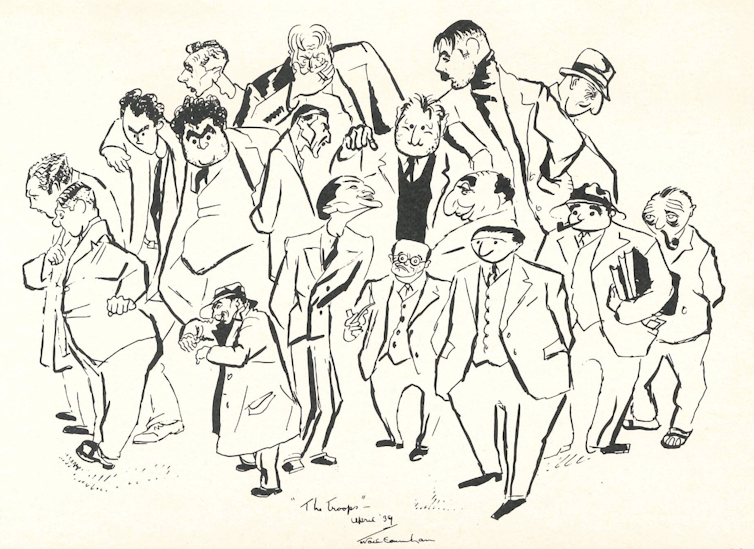

The scene at the Swanston Family has been vividly captured by many. Barry Humphries told The Sydney Morning Herald,

the noise was deafening, but the atmosphere was heady and as I stood in that packed throng of artists’ models, academics, alkies, radio actors, poofs and ratbags, drinking large quantities of cold beer, I felt as though my true personality was coming into focus.

People were the great attraction. All human life met there in a chaotic, crowded, and lively swill. Patrons included artists Clifton Pugh, Charles Blackman, John Perceval, George Johnson, Arthur and David Boyd; authors Frank Hardy and Alan Marshall; and journalists such as Clive Turnbull. Visitors from interstate and overseas would join the throng when in town.

Art historian, critic, and academic Bernard Smith described it as “the major social centre for Melbourne’s radical intelligentsia”; historian and author Manning Clark said it was the “best university” he’d ever attended.

Humphries refers to the Swanston Family in his essay Arthur Boyd: A life as a vile den that smelt of beer, urine and cigarette smoke. He met Boyd there. Patrons included “card-carrying alcoholics” and “academic tosspots”. According to Humphries, the exhilarating throng motivated his journey of self-discovery.

Another ritual of Melbourne’s bohemian set was to travel to Eltham on Friday nights, when the Swanston Family closed – to the area around Montsalvat Artist Community. There they continued drinking and carousing. This was known as “The Drift”, a title Humphries says was bestowed by Eltham resident, Burstall. In his diaries, held at the State Library of Victoria, there are accounts of the filmmaker drinking there alongside notes on who he met and what they did.

Germaine Greer was a member of The Drift during her undergraduate education in Melbourne and later intimately involved in “The Push” in Sydney. Comparisons have been drawn between these two subcultures, but there were distinct differences. According to Greer’s 2013 biographer Christine Wallace,

The Drift and The Push had a lot, and little, in common. Both groups flouted conventional standards of behaviour; their members were sexually freewheeling and dismissive of the social mores. The Drift was heavy with visual artists while, when it came to fine arts, most members of The Push had the aesthetic instincts of a barstool.

The Push was a left-wing libertarian group that operated around Sydney’s pub culture from the 1940s to 1970s. “Push” pubs welcomed women, as the Swanston Family did. Many Push members were people who came to work in the film industry and at its periphery (Margaret Fink, John Flaus, Eva Cox and David Perry from the avant-garde film group Ubu); well-known individuals who would have contributed to the understanding of The Push as an intellectual subculture of critical drinkers that included Robert Hughes, Clive James and Frank Moorhouse. The Push was strongly influenced by the University of Sydney and University of New South Wales, as well as trade unionists and the left.

Both The Drift and The Push championed a culture of free love. According to Steph – a Push member interviewed by granddaughter Lauren Lancaster in the University of Sydney student newspaper Honi Soit, whose surname is unrecorded – most members were men, so free love was an easy sell.

Steph described the culture as “chauvinistic”. One didn’t want to go against the ethos, she said, because if you objected you were bourgeois. But it was the women who were left with any unwanted pregnancies or the consequences of backyard abortions. The men bore no responsibility.

The Drift pushed boundaries and set the climate for the swinging 60s – although the 50s were swinging if you were in the right place! These fringe countercultures were precursors for an era that saw significant social, political and cultural change and activism – including the women’s movement, which was gaining momentum, anti-Vietnam war protests, and long overdue campaigns for Indigenous rights.

At the heart of it all was the city, and The Swanston Family, where Melbourne’s artistic and intellectual traditions met and matured. It was a melting pot for intellectual and aesthetic interests in an exciting exchange of ideas at a critical time in the history of our city. I think about this as I travel past that corner where the hotel once stood.

Gone now is any sign of all that went before, except for an original sewer vent – (now even that has been remodelled).

Melbourne-Sydney divide

In her biography of Greer, Untamed Shrew, Christine Wallace has described how Greer found The Drift completely different from The Push. There was a difference in their concerns – each was influenced by the individuals and distinctive social, cultural, and intellectual contexts of the two very different cities. In Melbourne, the conversations were about art, truth and beauty. Members of The Drift would argue with the person instead of addressing the argument’s merit.

Whether or not my parents interacted with The Drift I do not know, but certainly they knew many of the players, and much, much later I came to know some of them as well.

The differences between The Drift and The Push align with the well-known Melbourne–Sydney divide that has long been observed in sport, politics, fashion and art. As academic Mervyn Bendle observed in Quadrant, these movements are significant to any understanding of the intellectual traditions and milieus of each city. Bendle used historian Manning Clark’s article Faith (1962) to explain Victoria’s willingness to embrace a long period of Marxist socialism under former premier Daniel Andrews and his predecessors.

Clark situates Melbourne’s radicals as attracted to Karl Marx and ideas of collectivism and the all-powerful state, while Sydney’s lent towards Friedrich Nietzsche’s suspicion of the state and advocacy for individualism.

If one takes this idea for a walk, it leads to the idea that Melbourne’s intellectual life – which matured in bohemian venues such as the Swanston Family – drew on the struggle between different socioeconomic classes, anti-capitalism, alienation from products of labour, and communism. All of which position Melbourne as socialist, inclined towards regulation by the state, and interested in uplift through culture.

Six o’clock swill

Between 1915 and 1966 in Melbourne the pubs closed at 6pm. Wartime austerity and the temperance movement were to blame. Patrons responded by ordering as many drinks as they could before publicans stopped serving, which likely encouraged the rowdy behaviour and excessive drinking it was supposed to control.

According to my father, who by all accounts was one of the Swanston Family’s most frequent patrons, when the hotel closed all the men would spill onto the street, taking their glasses with them.

Many would cross the road and urinate on the corrugated iron fence on the other side. A lot of pubs were tiled on the outside to protect against this practice, but the Swanston Family was not. My father told me that the man who owned the fence opposite grew tired of the antics of Swanston Family patrons and one day electrified the fence. Dad observed drolly that he was lucky he did not need to piss that night!

The public bar was upstairs at the Swanston Family; downstairs was a meals area my mother Helen has described – with some emphasis – as “the passion pit”. She said the public bar was very small. The larger dining area underneath had a sign on the door: “Men will be accompanied by women”. Men weren’t allowed to enter without one (a kind of reverse sexism!).

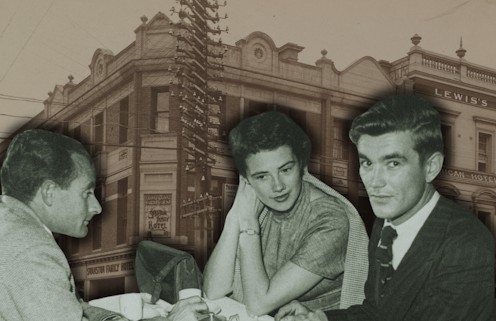

I have a photograph of my parents in the passion pit, looking very young and stylish. In my mind’s eye they are like Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Their relationship was similarly stormy and volatile, Len and Helen were glamorous, handsome, charismatic, chic and very much “about town” in the early 1950s.

On the left of the photograph is their friend, Doug Craig, who appears not to want to join in the image-making. Perhaps he is conscious of being an interloper? My father engages the camera directly; my mother’s demeanour is demure – although she wasn’t. Burstall describes her in his memoirs as my father’s “black panther mistress”; did he mean feminine power, sensuality, danger? Was she a femme fatale?

She is described from Burstall’s diary, published as Memoirs of a Young Bastard, as “a really good looker … In her early twenties raven haired, with flashing, dark brown, nearly black, eyes”.

It might seem strange that they appear to be drinking coffee in a bar – see the cups on the table – but licensing laws did not allow wine with meals in Victoria until the 1960s. Other couples are dimly reflected in the mirror behind them. Dad has a cigarette holder. Has he just been having a drag of hers? Cigarette holders were common for women, but it is quite a feminine gesture for a man in the 1950s – although there were famous men, such as Ian Fleming, Peter O’Toole and Tennessee Williams, who used them.

My father wasn’t feminine, but he liked to dress well. He didn’t want anyone to think he was “a bum”. In an account of the Swanston Family, in his essay on Arthur Boyd, Humphries recalls my father being mocked for wearing a new suit and describes that mockery as “malicious”.

It appears he had empathy for Len. My father certainly didn’t see himself as “a dandy”; I can imagine that as a young man making his way in the world such things might burn a sensitive and developing sense of self. Humphries’ colourful, exuberant, counter-cultural emergence would have been similarly in flux at that time: he was a bit younger than my father and was an unknown Dadaist Street performer. Anne Pender describes him as “the most daring student prankster Melbourne University had ever known”.

Spinsters’ rights

The Swanston Family Hotel was one of many in Melbourne to have female publicans but in the 1950s only married women were allowed to hold a licence. As historian Claire Wright observed in Beyond the Ladies Lounge, Mrs E. E. Mitchell of the Swanston Family Hotel lobbied with a group of female publicans for unmarried women to also be approved in the profession, challenging the liquor act restrictions.

The Melbourne Herald ran a story in September 1940: “Women Hotel Licensees Defend Spinsters’ Rights”. It was a pragmatic response to the capacities of women in business, not overtly a feminist campaign. One might speculate that the reasoning for allowing women to be publicans in the first place was sexist, likely rooted in a concept Anne Summers later describes as women being “God’s police”; good moral guardians.

Nevertheless, from the female publican’s advocacy for equity, we can discern a potential explanation as to why the Swanston Family had a welcoming stance towards women. Being a hotelier was one place women could be in business. In this regard that industry was more progressive than some other parts of society at the time. In a photograph taken in 1948 of these female publicans they look powerful, confident and not a group of women I would want to mess with!

Cafe culture

As the 1950s progressed, a new cafe society emerged in Melbourne. Cafes became as important as pubs for the bohemian set, enabling women to join. Most notable was Mirka’s Cafe in Exhibition Street (opening in 1954), and Pellegrini’s Espresso Bar (opening in 1954) and The Legend Cafe (opening in 1955) in Bourke Street. Each played an important role in the city’s counterculture. Many of the same people who met at the Swanston Family also frequented these cafes.

The Legend Cafe was established on the site of the former Anglo–American Cafe by that proprietor’s grandson, Ion Nicolades. He modernised the business, though kept a milk bar attached on one side, and renamed it The Legend. Nicolades approached up-and-coming designer and sculptor Clement (Clem) Meadmore to design the interiors. Meadmore then introduced Nicolades to my father Len, whose first commission was a series of murals for the premises.

The cafe’s name would come from the title of that mural: The Legend of Sinbad the Sailor (1956). There are seven bold, modernist panels, just as there were seven epic voyages of Sinbad. That myth comes from the 18th and 19th century, when Arab and Muslim sailors explored the world and the story of Sinbad worked its way into culture, describing the monsters and magic of his adventures.

Conversations between artists at the Swanston Family and elsewhere at the time often turned to experimentation. The artists were frequently poor, as there were few avenues to make money from their art, which led to great improvisation with materials. They shunned the traditional methods of the art establishment and embraced a DIY attitude using cheaper materials and a younger generation of artists were influenced by this trend.

Artist Gareth Sansom said that the Legend coffee shop mural based on Sinbad the Sailor had an enormous influence on him:

after seeing it in 1958, and the Melbourne University swimming pool mural, I raced home and started using my father’s Dulux house paint on Masonite … and my first exhibition featured some of those early experiments with paint … [French] was gruff and confrontational and talked like a Harold Pinter script – but always exciting, and an art star before Whiteley.

The Legend was featured in an exhibition at the Ian Potter Museum (2018–2019), and some artefacts are held in galleries – the National Gallery of Victoria has a “milk bar chair” from the cafe. While artists such as Fred Williams and Arthur Boyd went to The Legend in the mid-1950s, as my father did, for free pasta and a growing friendship with Nicolades, it was more a fashionable location than a truly bohemian haunt.

Perhaps the avant-garde had already begun to disperse.

This is an edited version of a chapter in the book Composite City, Arcade Publications.

The book Composite City had students from RMIT's Master of Writing and Publishing working on it as a collaboration with Arcade Publications.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.