The Mabo decision in 1992 was a turning point for Australia. It finally overturned the dishonest doctrine of terra nullius and recognised Indigenous land rights. It was a moment of hope, accompanied by a productive tension.

Mabo followed a decade in which awareness of the need to address Indigenous dispossession had grown. In the preceding years, sectors of the (white) settler population had begun to distance themselves from a triumphalist, uncritical view of the past. They had finally stopped looking away.

They had stopped looking away from shocking dispossession, disregard, and dismissal of the nation’s First Peoples. From the pretences of equality, a fair go and mateship. From the flattening of intersections of identity such as race, cultural backgrounds; and sexualities other than heteronormative.

An important cultural conflict, out in the open, seemed imminent. It would have been healthy.

Paul Keating broached some of that necessary conversation in the December 1992 Redfern Park Speech. Although that speech has been over-eulogised since, it was the first time that a prime minister used the pronoun “we”, naming settler Australians as the ones who needed to shift their attitudes and behaviour and take responsibility.

‘Comfortable and relaxed’ evasion

But the Mabo judgement also sparked a backlash which in 1996 contributed to the election of a new prime minister. John Howard immediately set about urging Australians to feel “comfortable and relaxed” about the past. Howard shifted the “We” of Keating to “Us” (and “Them”).

Since then, Howard’s masterful weaponisation of “us and them” as a cornerstone of national identity has influenced debates in literary and artistic circles. He transitioned the Australian psyche from Menzies’ forgotten people to Howard’s battlers – who eventually became the Morrison quiet Australians of the past four years.

Conservative governments have held office for the lion’s share of the 30 years since 1992. Their politicians have historically pitted those who are interested in advancing conversations (and genuine dialogues) around class, racial, and gendered equity against the “ordinary” Australian – usually still imagined as a white settler.

The robust public discussions around intersectionality, equity and diversity – along with social justice agendas and displays of ethnic identity and pride – that were coming to be considered healthy in a pre-Howard era were repositioned as a divisive “them” discourse. They still are.

I want to unwind the post-Mabo climate, and the continuing evasion legacy of the Howard years in settler writing, through examining some settler texts (the storytelling emerging from settler colonialism) spanning the late 1990s to where we are today, in 2022.

Read more: Live-streamed event: Top thinkers explore the life and legacy of Eddie Mabo

The Castle, Mabo and Howard’s ‘Us-Australians’

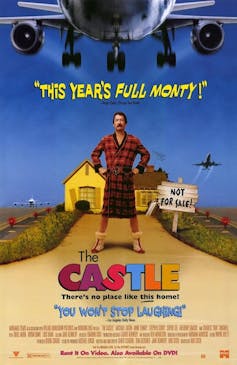

In 1997, a film hit Australian cinemas that nailed the Howard ethos and represented the “Us-Australians”. It set the blueprint for the largely flatliner, non-intersectional, evasive textual conversation to follow. The film was The Castle.

The Castle is the story of the Kerrigan family – portrayed as an ordinary, clean-living, working-class family in western Melbourne. The family live in a ramshackle home they have built themselves, just a few metres from Melbourne Airport in Tullamarine.

When their family home is condemned by a building inspector and plans are revealed, showing that the property is to become part of a government-planned expansion of airspace, the family enter a legal battle to save their family home. The plot of the film revolves around this battle.

25 years on, the timing of this film and its post-Mabo message are worth unwinding.

The film’s narrative verifies gender binaries, heteronormativity, larrikinism, healthy scepticism, surface egalitarianism and manual-hands-on type jobs. It verifies minimal engagement with national/current affairs, mateship, and the great Aussie illusion of luck and chance. It reflects minimum diversity always matched with jibes at difference, masked as humour (e.g. “the wogs next-door”). And it valorises an attachment to the Australian dream of private property, represented through a small corner of Australia – the suburban backyard.

Comic as The Castle may be, its overt ideology can be interpreted critically as enacting a self-reflexivity on the part of the viewer: a how-would-you-feel-if-you-were-the-Kerrigan-family moment. It undermines the disengagement from politics, national and current affairs that was being encouraged from late 1990s Australia, which is still persistent in popular settler texts. But it also enacts a disengagement with “other Australians who don’t have any property to start with”. It’s a story for the propertied only.

Daryl Kerrigan makes a brief and fleeting reference to “knowing how the Aborigines feel”, in having land stolen. It’s poised as a statement spoken to the nation for brief consideration, as if Daryl is saying it for everyone. His wife’s dismissal with “have you been drinking?” and Daryl’s short rejoinder, “people have got to stop stealing other people’s land in this country”, are striking for the way the sentence is allowed to hang – inviting the rest of the “Us-Australians” to whom John Howard was talking to finish the statement. Moreover, the audience can.

I think it is no accident that the moment is poised and framed this way: to allow the viewer time for a quick mental calculation between their “little piece of Australia” and the vast tracts of Australian First Nations land that Howard’s government positioned as “under threat from Native Title” when he used a pendulum to describe Australia’s swing towards recognition of First Nations sovereignty (and the need to address it through the 1996 Wik Ten-Point Plan).

What doesn’t Daryl Kerrigan say? Where does he not go? Which people and whose land? Which land has got to stop getting stolen? And when it’s got to stop? And what of the intersections of identity, and the entanglements between First Nations peoples, settlers, and many different diasporas to Australia since – left unexplored in this statement, in this text – who have been largely evaded in Australian mainstream literature since?

Also – how polite is the text? It’s the ultra-genteel working-class backbone of Australia on display. Howard ushered in, and his legacy left, an era of the dangerous politics of settler civility – the language of euphemism and evasion.

There’s nothing about the Kerrigan family that threatens the status quo of the “Australian Dream” and the mythscape of a united nation.

The Kerrigans’ challenge to the system is positioned as a healthy insurgence – the Kerrigans’ quarter acre is inconsequential to the state. Their win is positioned as a concession to a good family by a benevolent system. The film glorifies white crime as Aussie larrikinism – there’s a son in jail, a scene with a firearm, a scene where a truck is used to tear down someone’s front gate.

The film upholds a landmark case, for which and whose land (or property) really is sacred in post-Mabo Australia – and it’s not First Nations land. At a time when right-wing politicians and newspapers were arguing against native title, The Castle sold a story to a nervous nation that was quite reassuring.

Think about the casting. How would these roles fly with a family that’s anything other than white? What sort of appeal would the film have had (and still have) if the family at the centre, fighting for their piece of land, were Aboriginal? Or Lebanese?

Can you imagine the different reaction if a First Nations protagonist or a protagonist of Islamic heritage had pulled down the gates to someone else’s property in a tow-truck, or pulled a gun on someone? Would it be funny then?

Imagine a First Nations family being as relaxed as the Kerrigans are about their son – or anyone – being incarcerated. An audit of secondary social science and humanities curricula that I undertook in 2020 revealed that The Castle is the most taught text in units relating to identity and culture in Australian high schools. This film is a canonised text for Australian settler identity.

At the end of the Howard era, Australia’s Indigenous population was in a ruinous state. Australia’s extraordinary natural environment was threatened on numerous fronts, and its people were beginning to ask where the wealth had gone. Public schools and public health were in crisis, social welfare was decimated, housing was unaffordable for many, and wages and conditions were being cut under Howard’s industrial reforms.

At the height of the 2001 election, when 400 refugees were rescued from a sinking boat and left stranded in the tropical heat on the deck of the Tampa, Howard publicly refused permission to land the refugees in Australia. His immigration and defence ministers claimed that refugees had thrown their children overboard, leading Howard to declare: “I don’t want people like that in Australia.” Only after the election was it proven that the government had known the claim was false.

Truth became an inconvenient detail from here on. We entered an era of post-truth. The nation’s already murky relationship with its hidden truths – its settlement by invasion, massacre and cultural genocide, and the continued legal fiction of terra nullius – were relegated to the spectre of irresolution that hangs over of the nation.

At the heart of the legacy of Howard’s 11-year era is an unease, and (dis) ease – something deeper that Australians would perhaps rather not admit. For a decade, Howard’s power had resided in his ability to speak directly and powerfully to the great negativity at the core of the Australian soul. Its timidity, its conformity, its fear of other people and new ideas. Its colonial desire to ape rather than lead – and its shame (which sometimes seems close to a terror) of the uniqueness of its land and people.

The country was frightened: unready for the great changes it must make, and ill-fitted for the robust debates it must have.

Read more: Post-truth politics and why the antidote isn't simply 'fact-checking' and truth

Alexis Wright’s overtly political, ‘distinctly First Nations’ debut novel

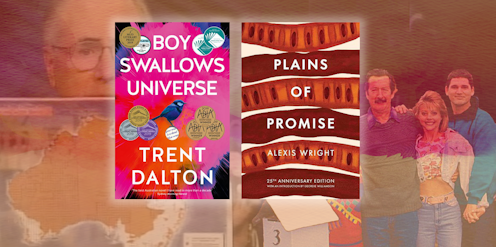

Released in 1997, the same year as The Castle, paralleling the narrative of “Us”, was Plains of Promise, the debut novel by Waanyi writer Alexis Wright.

Alexis’s work arrived with much less fanfare – it was neither subtle nor polite, amid its intricate plot and beautifully crafted words in the language of the coloniser. Plains of Promise spoke to the “Them” – those “other Australians” outside of the “Us” that Howard claimed to be governing for.

Plains of Promise is a story of mothers and daughters who endure and survive a series of colonial interventions. A story of the intergenerational trauma of separation, dispossession from land, and repeated sexual assaults of Aboriginal women at the hands of white men and black men who have internalised the worst of settler behaviours. The novel ends with a powerful allegory that alludes to a precarious future for First Nations peoples under conservative governments.

Wright’s narrative is a brutal parody of settler texts like The Castle, and the Howard-Australian mythscape that evoked Russell Ward’s Australian Legend of egalitarianism, mateship, larrikinism, anti-intellectualism, and healthy, non-threatening anti-authoritarianism.

Plains of Promise posits an overtly political, distinctly First Nations, and determinedly fictional and literary account of Indigenous peoples’ experiences in Australia. It’s a text that writes at the intersectionality of racism, sexism, classism, ableism, chauvinism; and all that hover in the spectre of irresolution and dis-ease above the nation – and the bearing that these intersections and entanglements have on the First Nations, Waanyi protagonists of the novel.

With its particular focus on the way the intersections of sexism, classism, ableism, and racism impact the lives and futures of Waanyi women, Plains of Promise is the total antithesis of: A man’s home is his castle! Alexis achieves this through making First Nations identities visible and complex, and by highlighting ongoing colonial dispossession and struggles for land rights and recognition.

We are now living under the spectre of post-Howard euphemisms that locate truth as divisive. First Nations people are labelled as rude or confrontational if we point out cultural chauvinism in settler language or call out skin privilege or white fragility. Under Howard and his “Us-Australians”, charges of “identity politics” were levelled against “Them-Australians” – and identity politics were positioned as both anti-Australian and anti-art. This remains the case.

Read more: Read, listen, understand: why non-Indigenous Australians should read First Nations writing

All writing is identity politics

Attacks on “identity politics” and the construction of an ideological hard binary between ethnic identity and art and literature are legacies of post-Howardism. Yet the idea that any artwork or piece of literature is free of cultural value is mythical and warrants interrogation.

Some terms are used a lot, but rarely deconstructed – like the slippery charge of “identity politics” in art and literature. So, the scientists have been telling us for some time that the concept of race is dead. I don’t dispute what it all looks like under a microscope, but socially and politically, the term and all its connotations are alive and well – in literature, art, music, policy. And the terms “race” and “culture” are conflated in Australian discourse.

Together, these words drive Australian national policy and historical discourse. The politics of race, the politics of skin privilege and the politics of representation have been cornerstones of Australian policy and practice since invasion. Literature is the handmaiden who tells this tale. White identity politics is the most dominant force of production in Australian settler literary culture.

Charges of identity politics impeding art have only entered the public space since First Nations people and people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities have infiltrated the space, and now use it and some of the “tools” it affords to tell their own tales – or stories.

These presences challenge the unspoken identity of white-settlerism and make identities explicit – and explicitly political, as they have been politicised in public discourse. Charges of “identity politics” come from those who now have to concede space – and see themselves represented, not always to their own liking, in someone else’s picture or story.

All creative pieces are identity politics in some way or other. All writing is identity politics: from a shopping list to a treatise on government and all in-between.

Read more: The Black Lives Matter movement has provoked a cultural reckoning about how Black stories are told

Popular settler texts, post-Mabo

So, how am I reading the settler landscape of influential writing post-Mabo, and in the aftermath of Howardism? Influence is decided by the literary economy of prizes, and the public visibility of a text.

In the main, settler texts are still repurposed, largely intersectionless battler narratives, where the protagonists battle different obstacles depending on the times. Or, as Sujatha Fernandes put it so well in her 2019 essay for the Sydney Review of Books, they are “great white social justice narratives”. Though they may read as concern, really the writer should be yielding space for those they are so concerned about to speak, write or tell their own stories.

Popular settler literature in post Mabo-Australia (and literature on the border between literary and popular) still loves to be a “good battler narrative”. The best battler is the battler who succeeds. The one who is aspirational within a recognisable setting.

And the best battler narrative re-enforces a meritocracy and the myth of a classless, raceless, society, where intersectionality is irrelevant. It continues to erase deeper, more complex, and contested histories of place. It’s a place that flattens or erases intersectionality – racial/cultural background, orientation/sexuality (what is your pronoun?), age, ability, religion/spirituality, socio-economic class – and the complex and contested histories of place.

What can we learn about contemporary Australia from its popularly and critically acclaimed novels – and their success? This is a question that critics and reviewers have been reluctant to broach. Critics tend to avoid writing about popular works, as part of an intra-cultural cringe.

But by refusing to engage, they’re in danger of writing into a blinkered, self-informed space that reproduces a very narrow view of Australian national identity and the values it perpetuates in its literature.

Read more: The larrikin lives on — as a conservative politician

Trent Dalton’s superficial melting pot

A popular writer is the public’s barometer. The optimistically conservative view of national identity – Australianness if you like – that was aired in The Castle 25 years ago has carried through to the popular literature of the moment. You only need to look at Trent Dalton.

Unlike many popular, big-selling Australian authors, Dalton’s writing has been listed for prestigious awards. His first novel, Boy Swallows Universe, was longlisted for the Miles Franklin Award in 2019. At the NSW Premier’s Prizes, it won the Glenda Adams Award for New Writing, and the People’s Choice Award, and was shortlisted for the Christina Stead Prize for Fiction.

The plot of Boy Swallows Universe revolves around the coming of age of teenager Eli Bell – son of a heroin-addicted mother, an alcoholic father, a drug-dealing stepfather; and brother to Gus, an elective mute since age six. As the story unfolds, Eli overcomes many obstacles and learns much about being ‘street-wise’ from his babysitter Slim, a convicted murderer. The plot is driven by Eli’s largely individualistic quest to determine what a “good man” is.

Boy Swallows Universe is apparently the fastest-selling Australian debut novel ever published. With one exception I’ve found, reviewers have been laudatory. The labels of “literariness” could be because both Dalton’s works are laced with literary allusions, and brief and fleeting references to western classics. For example, an orphaned teenager, Molly, carries The Collected Works of Shakespeare in their duffle bag; Eli is well versed in the 20th-century white male canon, and often bursts into optimistic streams of consciousness, in a way that is meant to evoke James Joyce.

Such literary allusions and references reassure readers that these works and their protagonists are literary, despite the grungy realism of the settings; and that the western literary canon endures.

In the one critical review I could find (in the Sydney Review of Books), settler critic Catriona Menzies Pike described Dalton as the “Scott Morrison writer” of the decade. Howard’s “battlers” segues seamlessly into Morrison’s quiet Australians who have a go to get a go.

All Our Shimmering Skies is Dalton’s second novel. Set in Darwin in 1942, it’s about teenager Molly Hook’s quest to remove a curse she believes was cast on her family by an Aboriginal man called Longcoat Bob. To me as an Aboriginal reader, Longcoat Bob, penned in 2020, resonates with an ongoing colonial trope – that of the part-Aboriginal (sic) child, and the black witch-doctor-sorcerer stereotype in settler literature. From Marbuck in Charles Chauvel’s 1955 film Jedda the Uncivilised to Bobwirridirridi in Xavier Herbert’s Miles Franklin award-winning work Poor Fellow My Country (published in 1975), through to Craig Silvey’s Jasper Jones, 2009 – the trope lives on.

In Shimmering Skies, the “our” pronoun, in Dalton’s hands, becomes a conduit for a melting pot. Evoking the language of evasion and euphemism, a group of “diverse” people – whose differences are superficially and stereotypically represented throughout – can put all differences (which aren’t explored anyway) aside and unite under common symbols, traditions, and icons.

We’re given a painless, quick, sentimental version of reconciliation that basically involves finding aspects of settlement to celebrate – with no basis whatsoever for land rights or reparative justice. Readers are presented with chess-set characters in starry campfire scenes that bring together Yukio, a Japanese pilot; Greta, a woman of German heritage; Molly, an orphaned teen; and her Aboriginal friend Sam, as they discover their common humanity as bombs explode in the sky.

Catriona Menzies Pike writes:

Dalton presents a national domain in which no obstacle is too great for an earnest and well-intentioned individual to overcome on their own. There is seemingly no ill in the world that can’t be sentimentalised by Dalton: prison life, addiction, violence, colonialism. There is no insight into contemporary life here, just fantasy built on nostalgia and dishonest nationalism.

Boy Swallows Universe and All Our Shimmering Skies offer Hollywood endings, where kids haul themselves up and out of poverty and disempowerment, through strength of will and character.

These stories give literary and social value to a narrative that relies on and reinforces pernicious, dangerous, and untrue ideas about poverty and social marginalisation – mainly, that it requires nothing more than effort to get out of it. Socio-economic success and security simply become questions of individual moral fortitude, altruism, and determination. Systemic structural failures are not called into question.

The only role for First Nations and people of colour in Dalton’s national epic is to advance the plot. The people brought together under the shimmering skies are settlers. All Our Shimmering Skies wants a quick and easy, group-hug reconciliation – but the text doesn’t want to recognise the violence of settler colonialism and ongoing dispossession.

In his fiction, Dalton refuses to acknowledge that there’s anything structural about the suffering his characters must endure. There’s no room for state intervention or reform in these worlds.

Both works unequivocally disseminate the same intensely conservative vision of nationhood and identity as The Castle.

Ethnic and gender stereotypes abound – but as Menzies-Pike points out, the difficult questions about representation and cultural appropriation that are recently being asked of literary authors have not been raised in relation to Dalton’s fiction. Such issues are seldom raised in relation to popular fiction because it is too easily dismissed.

Ignoring the popular makes us ‘part of the problem’

Different sets of rules apply to popular (or genre) fiction and literary fiction. Definitions tend to centre around literary fiction being more driven by character and theme, while popular commercial fiction is driven by plot and lots of action – and distinguished by higher book sales.

Whether it is clever marketing on the part of publishers, or whether it is driven by intellectual snobbery and elitism, the divide between popular (or genre) and literary fiction leads to a disconnect between what is being read and internalised by the public, and what is being analysed as good literature.

This separation between “literature” and the rest of culture is unhelpful. Popular culture should be held to the same high standards as literary authors – which means that critics, academics and the rest of the self-selected elite need to properly engage with it. If they do, they will unpack what is driving its mass appeal.

Nurturing critical thinking is the responsibility of all of us who read literature and care about issues of representation. All of us who care about exposing and addressing structural inequalities and systematic discrimination. If we only focus on changing the “literary” culture we read, but ignore what mainstream Australia is reading, then we’re part of the problem of Australia’s continuing evasion discourse.

Read more: The courage to feel uncomfortable: what Australians need to learn to achieve real reconciliation

Jeanine Leane receives funding from ARC grants.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.