They are antique car aficionados and struggling students. They are retired people living in the countryside, cheerful multilingual accountants who have lived abroad, and even frustrated, disadvantaged members of the country’s Muslim minority.

What binds them is an intent to vote for Marine Le Pen, France’s far-right candidate, who appears to have successfully smoothed out the harsher edges of her image as a proto-fascist bigot and arrived within striking range of the presidency.

“Voting Marine Le Pen in 2022 has nothing to do with racism or fascism,” says Nathan Gazzoli, a 19-year-old student in Toulouse and a first-time voter. “It is a vote for the people.”

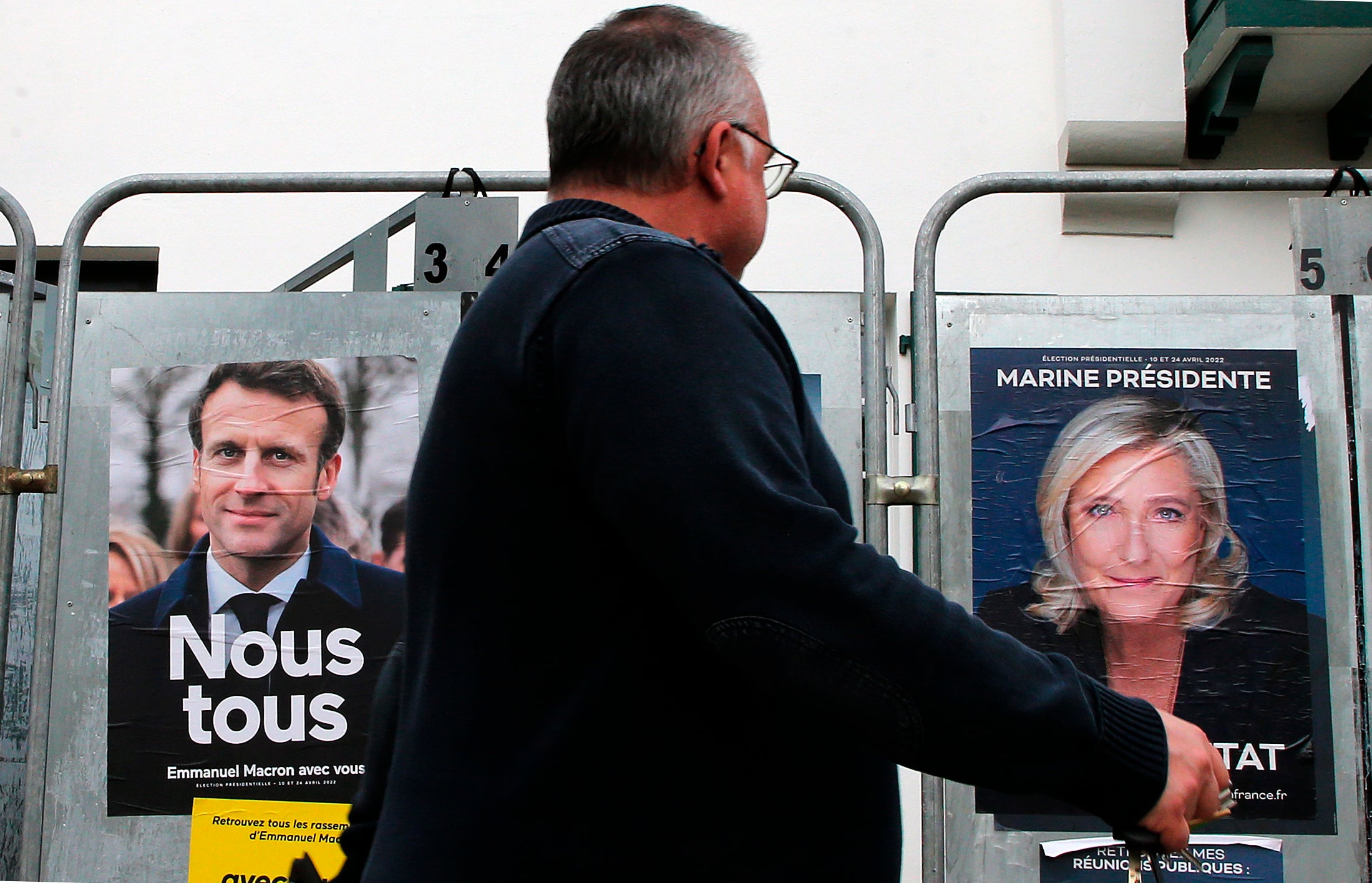

While most polls show incumbent president Emmanuel Macron narrowly winning the vote, a stunning survey by Atlas Politico on Thursday showed Ms Le Pen, heir to the far-right National Front party founded by her father, Jean-Marie, edging out Mr Macron by 50.5 per cent to 49.5 per cent in a hypothetical second-round match-up.

The French head to the polling stations on Sunday for the first round of elections, which come at a particularly crucial moment in European history, with Russia waging war against Ukraine and the world emerging from a two-year pandemic.

Ms Le Pen, who has been campaigning aggressively across France – and even abroad – for months, initially spurred doubts when she shifted her rhetoric away from immigration and cultural issues, which were the core of her father’s political platform, and focused on economic matters such as inflation, purchasing power and the retirement age.

Her stump speeches became more Jeremy Corbyn than Viktor Orban, the Hungarian prime minister whom she considers a close ally.

“If the purchasing power issue is strangling you today, it’s because previous politicians have impoverished you, have made public accounts collapse, and have even put our children into debt for a long time,” Ms Le Pen told a crowd in the southern city of Perpignan this week.

That shift is now vindicated, as her party, Rassemblement National (National Rally), is poised to perform better than it ever has in its 50-year history.

“I believe in France,” she said in an interview this week with The European Conservative. “I dedicate every second of my life to the happiness of the French people, who are the top priority in all my battles.”

Although Ms Le Pen is still behind Mr Macron in all but one poll, she has made up significant ground in recent weeks, while the French are notoriously fickle when it comes to their voting intentions.

In polls conducted just a week before the election, a third of the electorate said they might still change their voting intention and dump their preferred candidate. Both the left and the right of the political spectrum are crowded, while Mr Macron is the undisputed champion of centrists.

“What matters to me [is] to go and convince people who are tempted by extremes that extremes do not provide the right answer; that the fears people have are sometimes legitimate, but the real answer is different, and it can sometimes take time,” Mr Macron said in a radio interview earlier this week.

Mr Macron has seen his lead in the polls fade since March, having lost favour in the light of conservative proposals such as raising the retirement age to 65, cutting inheritance tax, and tightening access to welfare benefits.

The president has also drawn criticism from some voters who feel he has focused more on diplomacy over Ukraine than on domestic matters. Mr Macron said on Friday that he regretted entering the presidential race late, explaining that he had done so on account of Vladimir Putin’s war.

Meanwhile, turnout on Sunday is expected to be low, with one poll suggesting as many as 30 per cent of voters could abstain.

But that could change as alarm bells go off about the surging candidacy of Ms Le Pen, whose name, along with that of her father, still evokes shock and derision among some quarters in France. A second and decisive round between the two winners of Sunday’s election is scheduled for 24 April.

A lot will hang on the young voters, and whether they show up on Sunday. In last year’s regional elections, no fewer than 87 percent of them chose not to vote. And while presidential elections generally elicit more enthusiasm, some studies predict that up to half of the youth electorate may abstain.

“More than half my class is not planning to vote this Sunday,” says Mr Gazzoli. “This pains me because I consider voting not just a right but also a duty. We are being asked to help decide our future.”

Up until a few weeks ago, Mr Macron, a 41-year-old former investment banker, looked to be sailing towards an easy second-round victory.

But he has become embroiled in a disastrously timed scandal involving hundreds of millions of euros paid to consultancy firms to advise the state on the Covid crisis. Mr Macron has defended his government, but the saga has drawn criticism from the right and left, reinforcing the view that he is an out-of-touch elitist more focused on the interests of the super-rich than on those of ordinary French people.

“He stigmatises and he despises the unions by saying that, in the classrooms, there are teachers who do the ‘union minimum’ vs the teachers who do more,” Yannick Jadot, the Green Party candidate, said on Thursday, according to Le Monde. “I find it shameful.”

The failure of the left-wing contenders to unite under one candidate has benefited both Mr Macron and Ms Le Pen.

Jean-Luc Melenchon, the leader of the far-left La France Insoumise, has also surged in polls in recent weeks, but not nearly enough to reach the second round. He has also campaigned on economic issues and sought to address voters’ daily concerns, but has been pilloried by the candidates of the Socialist, Green and Communist parties.

Mr Gazzoli says many of his peers are left-leaning and routinely call him a fascist and a racist because he is a Le Pen supporter. He is no fan of far-right candidate Eric Zemmour, who posed a serious threat to Le Pen earlier on in the campaign but has recently plummeted in the polls.

“Zemmour talks a big game about security and immigration, but if you want to run the country that is not enough,” says Mr Gazzoli.

“Marine Le Pen has been very smart in talking about both security and the cost of living,” he tells The Independent. “She has spent a lot of time talking to the older people who have trouble making ends meet.”

A win by Ms Le Pen, or, less likely, Mr Melenchon, would have far-reaching geopolitical implications for a country that is the EU’s second-largest economy, even though the French parliament would be able to rein in their ambitions. Ms Le Pen allegedly owes millions of euros to banks operated by Kremlin-linked oligarchs, and has voiced anti-European Union and anti-Nato commentary.

Mr Melenchon, on the other hand, “is basically so anti-American, he supported all the dictatorships that were anti-American,” said Mr Jadot.

Mr Gazzoli predicts that both far-right voters and supporters of the left will rally to Ms Le Pen in the run-off.

“What we have in common with the left is that we all agree that another five years of Macron would be a catastrophe,” he says. “[Ms Le Pen] has never been closer to victory.”

Gert Van Langendonck contributed to this report