Queen weren’t in the greatest of moods when they arrived in Montreal in late November 1981. Their tour in support of the previous year’s The Game album was supposed to have wrapped up a month earlier in Mexico. Yet here they were, having loaded up 17 massive semi-trailer trucks and brought their 51-strong crew north to play a pair of shows at the 18,000-capacity Montreal Forum.

“We’d done a hell of a lot of touring by that time, and it was time to take a rest,” says Queen guitarist Brian May, speaking at London’s BFI IMAX cinema ahead of the UK premiere of the restored version of Queen Rock Montreal, the concert movie filmed at those two shows. “Unfortunately, our manager, the illustrious Jim Beach, had done a deal in which we would play in Montreal. That was hard for us. We were already slightly grumpy about that, not just because, physically, we needed a rest, but also because you have to re-gear up. You’ve finished a tour, you’ve got all your crew, and they’ve all gone to different places, and suddenly for these two shows you have to bring everything back together. Everybody was a little bit huffy and puffy: ‘Why are we doing this?’”

The man who had persuaded the redoubtable Beach to agree to these shows was Saul Swimmer, an American producer, documentary maker and sharp operator who had directed George Harrison’s Concert For Bangladesh movie. Swimmer’s pitch was to film the Queen shows in Double Anamorphic 35mm, a new technology which would allow him to project the footage on a massive, five-storey high screen. The similar IMAX format had been developed in the late 60s, but it was largely confined to use in a few museums and science exhibitions. Swimmer saw huge commercial potential in his super-sized format. What’s more, he had the idea of projecting it onto huge mobile screens that could be taken to different locations. And Queen would be the band that could make it happen.

“It was a screen which could be put up outdoors somewhere to make these huge gigs where we weren’t there but people would still have a Queen experience,” says May. “And the whole thing could be driven around. Saul Swimmer called his dream vision ‘MobileVision’. What could possibly go wrong?”

Despite their huffiness, the fact that the gigs were happening in Montreal was a plus for the members of Queen. “Montreal is one of our favourite cities, it’s a great audience there, very full of energy,” says May. “We’d played this particular venue, The Forum, three times before, and it was always full of really enthusiastic people giving us a lot of energy back. So that part of it was good. We knew once we got onstage it was going to be great.”

Still, getting to that point proved to be more than a little bumpy. The crew Swimmer had hired hadn’t filmed a live show before. “They had no idea how much in the way they could possibly be, how disruptive,” says May. “They started putting cameras all over the stage. We immediately said, ‘This is never going to work.’ So there was a big, big argument about cameras onstage, which was never really resolved.”

The tensions were ratcheted up even further when the band were informed that they needed to wear the same clothes for both shows so the film-makers could cut between the two, something Freddie Mercury was not happy with.

“Freddie goes completely berserk and says: ‘I’m not being constrained in my wardrobe. I will wear what the fuck I like!’” says May. “It becomes a huge row. Jim Beach came in and tried to make peace: ‘Look, Freddie…’ And Jim gets banned from backstage. Bless him, I do apologise to him for that now.”

According to May, the band were still bristling when they went onstage. “We’re getting more and more grumpy, and you can see that in the film,” he says. “We’re very, very hyped up, some of the tempos are really fast, there’s a lot of really incisive, angry playing. You can see it in Freddie, I think.”

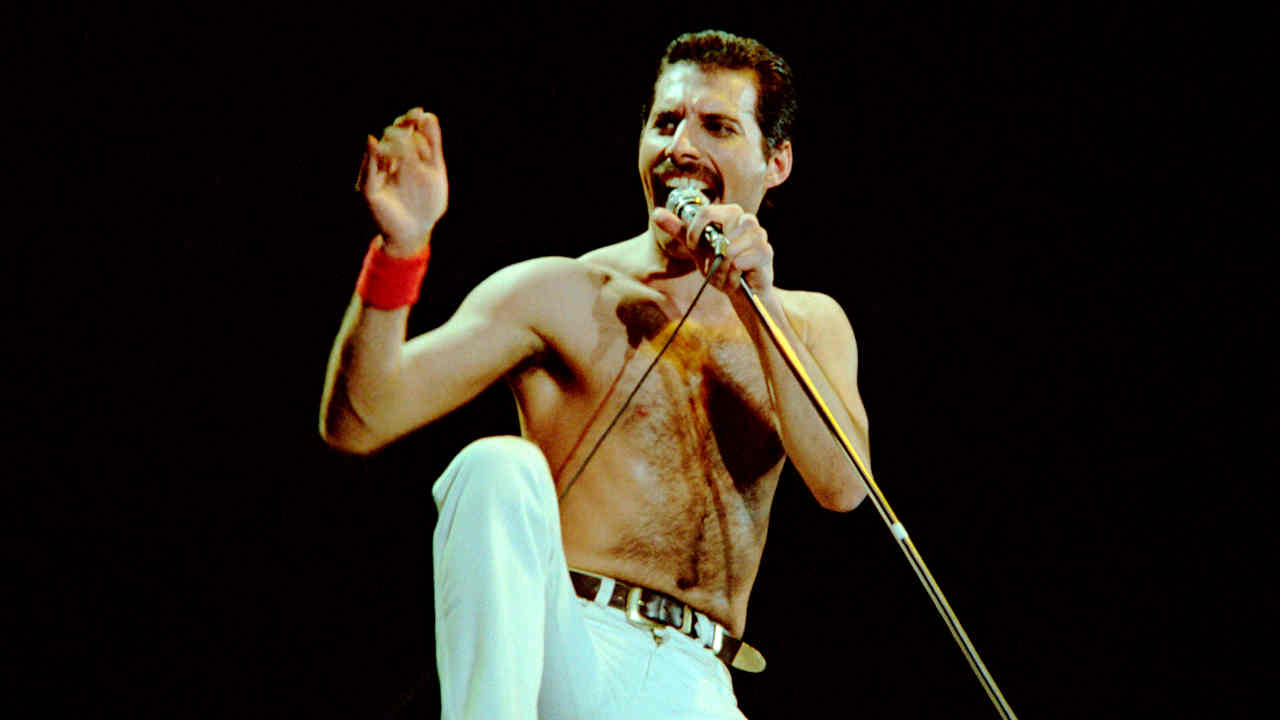

The show that Swimmer filmed captured a band at the height of their second act. The satin flares and Zandra Rhodes blouses of their early years had given way to contemporary outfits, sleeveless T-shirts, chic scarves and, in the case of Mercury, a handlebar moustache and some precariously tight white shorts. Musically, too, it presented a rawer version of the Queen who wrote such ornate works as Bohemian Rhapsody and March Of The Black Queen over half a decade earlier.

“We were at the top of the game,” says May. “We’ve had Crazy Little Thing Called Love, which was on The Game album, Save Me was on that album. And then out of the box comes this little track called Another One Bites The Dust, which, against anyone’s expectations, had become enormous overnight when it was picked up by some radio stations in New York who thought we were black.”

The shows themselves were a ringing success, despite the band’s initial reservations, and the ground-breaking technology used to film the performance meant the whole thing could be projected on the massive screens Swimmer had in mind. Except there was one problem: MobileVision was a little too mobile.

“We have to look at Saul Swimmer’s stroke of genius - this film, hi-quality, great,” says May. “Big, big screen outdoors? Not so great, because it acts like a sail and it nearly fell over a couple of times.”

Saul Swimmer’s grand idea to use the concert film to launch MobileVision never happened. Instead it was released on VHS and Betamax in 1982 under the name We Will Rock You, after the song that opens the show and is revisited as the penultimate encore.

Queen themselves were unhappy with the finished product. While the original footage looked great, it lost quality when it was transferred to video tape, and there were clear syncing errors at times between the music and visuals. As Swimmer’s production company owned the rights to it, there was little the band could do about it.

“For most of our career, it was a thorn in our side,” says May. “It was something that was never right. It was badly mixed, a horrible dry sound, with no audience on it so you didn’t get the atmosphere. It was badly edited, badly put together, and the original sync was done by eye, so every time they did an edit the sync would move. So it was really always something we were embarrassed by.”

The new, restored version of the film, retitled Queen Rock Montreal, rectifies that. According to May, “months and months of work” went into fixing the problems. The film is being re-released this weekend at IMAX cinemas around the world – ironic given that Saul Swimmer’s original idea was to use the movie to launch his competitor to IMAX. For Brian May, Queen Rock Montreal is a snapshot of a band in their early 80s prime.

“You see four young guys, we’ve already been around the world a lot of times, we’ve sold a lot of records, we’ve had a lot of hits, we know how to play with each other,” he says. “I feel quite proud of how we were at the time.”

At the same time, for the guitarist, it’s a reminder of just how unique a frontman Freddie Mercury really was.

“You’ll notice that a lot of the time, you don’t see us in this film, you see Freddie,” he says. “I think at that time, that was also a source of consternation for us, because we’ve always been a band. Now, looking at it, it’s such a boon, because now we don’t have Freddie, it’s wonderful to watch the world through his eyes. I can’t think of any other record of our shows in which you are so intimately in contact with Freddie. You see everything that’s going on in his head, you can see his anger, you can see his insecurity, you can see his consciousness that he can move people right to the back of the auditorium. To me, it‘s very emotional to watch him.”

Queen Rock Montreal is re-released on IMAX from January 18-21. More details here