This piece was produced in partnership with Texas Public Radio. Listen to the Texas Public Radio podcast series, “The Ghost of Frank J. Robinson.”

Dorothy Redus Robinson didn’t believe in ghosts, but she always said she knew her husband was murdered because his ghost told her so.

In an interview recorded when she was 85, Robinson said she was sitting on the edge of her bed days after Frank J. Robinson’s funeral when she saw him again.

“It looked like he came to the hall and stood at the bedroom door, and he said, ‘Dear, it’s a lie,’ and I said, just as plain as I’m talking to you, ‘You don’t need to tell me, I know you didn’t kill yourself.’”

Dorothy said she was wide awake by the time the conversation ended.

“Then he just faded, just faded back,” Dorothy added. “He didn’t come forward. I didn’t see any movement of arms or legs.”

In life, Frank J. Robinson had always been one to come forward. He was a fearless civil rights leader and voting rights advocate who broke down barriers for Blacks in East Texas. From his home base in Palestine, Robinson, then in his 70s, was actively leading an effort called the East Texas Project in the 1970s.

In 1973, he filed Robinson v. Anderson County Commissioners Court in federal court and successfully harnessed the Voting Rights Act to end the gerrymandering of Black voters at the county level in East Texas, a practice used to dilute their power at the polls.

By 1976, he planned to expand on his legal victories and export his strategies of empowering Black voters to surrounding counties. He was planning further action to register and organize voters to help elect Black candidates, too.

Then, on October 14, 1976, 74-year-old Robinson was found dead in his garage. That morning, his body was discovered by a neighbor, John Cook, who came by to ask for some of the watermelons that Robinson was growing in a lush backyard garden.

Cook knocked on the front door and when no one answered, he went to the side door next to the garage. There, he spied a pair of legs laid out in a pool of blood on the garage floor.

He ran next door to Story Elementary School for help.

Palestine police were called and found Robinson stretched out on the concrete floor. The top of his head was blown off and there was a double-barreled 12-gauge shotgun lying across the body. (The records conflict on where it was found).

Palestine Police Chief Kenneth Berry immediately determined this was a homicide. “From the evidence gathered at the scene, an autopsy report, and the information taken from his widow, we have concluded it was not a suicide,” Berry told a reporter for the Palestine Herald Press.

Dorothy was out of town the day her husband died. As president of the governor’s Advisory Council for Technical-Vocational Education, she had been in San Antonio and then in Minneapolis for conferences.

The last time she’d spoken with Frank was by telephone October 10, only three days before his death. “I called him Sunday afternoon after I got to Minneapolis and he said, ‘We’ve had a little cold snap and I can’t find my long underwear.’”

Dorothy told him where to find it. “But you won’t freeze to death till I get there,” she teased. She told him that her plane would arrive at 10 o’clock that Thursday. “And he repeated the time. And that was the last conversation we had. Probably the last thing I heard him say except ‘goodbye.’”

When her plane landed in Tyler, Dorothy knew something was wrong when she didn’t see Frank. “I could always see him standing out because the plane was so small,” she said.

“When I got out, my sister, her husband, and a friend and his daughter were standing there, and I said, ‘Where is Frank?’”

Dorothy’s sister threw her arms out but didn’t say anything. The friend’s daughter said, “dead.”

“Car wreck?” Dorothy asked.

“No, somebody killed him,” she said.

“Well, get my luggage,” Dorothy said. “I’m ready.”

By the time Dorothy got home, police had already cleaned up, removing almost all signs of the violent attack. Dorothy would later argue that in their rush they destroyed valuable evidence. But some gruesome artifacts of the horror weren’t so easy to wipe away: Some of her husband’s brain matter remained on the wall.

Police questioned Dorothy. They wanted to know “if I had any inkling that he had been threatened,” she said.

Frank often received anonymous, menacing phone calls but ignored them.

“He was just that dedicated to bringing change to East Texas,” Dorothy said. “So often he would say, ‘Change is always painful,’ and he’d say, ‘But what is a little bloodshed? Because it takes that to get change—my blood or yours or anybody’s. Blood changed a lot of things.’”

Berry had been Palestine’s police chief for a year when he began investigating Robinson’s death. He had previously worked as a lieutenant in the Waco Police Department, where he oversaw the vice unit. Berry would go on to serve as Palestine’s police chief for four years before becoming Palestine’s city manager. This was by far his most controversial and sensitive case.

Some of the people whom Frank had angered through his work were Berry’s bosses: members of the Palestine City Council.

Robinson’s death happened only a week after he had won a legal fight to force that governing body to create single-member districts. The lines were redrawn in a way that enabled the city’s first two elected Black council members to take office.

News of Frank J. Robinson’s murder made it into newspapers across Texas and around the nation. The Call, an African American weekly newspaper in Kansas City, Missouri, carried the story with the headline “Civil Rights Leader in Texas Shot and Killed From Ambush.”

The Associated Press quoted Police Chief Berry: “We have no suspects. We do have leads we’re working on.” Berry made a plea to the public for any information.

A group of prominent Texas Black leaders immediately questioned whether Berry would be able to solve Robinson’s murder and called for assistance from outside law enforcement agencies. Those who called on the Texas Rangers and the FBI to probe the death included John Warfield, a University of Texas professor after whom the school’s Center for African and African American Studies was later named; and state Representative Paul Ragsdale, a Democrat from Dallas.

Warfield, a controversial scholar and civil rights activist, described Robinson’s death as a “Ku Klux Klan style of murder and terror.” He declared it to be part of “a conspiracy in this state to obstruct the political rights and political awakening of Black and brown people and the powerful potential constituency they represent.” By “conspiracy,” Warfield said he meant the actions of state leaders, including Governor Dolph Briscoe, in opposing the Voting Rights Act.

Warfield thought Robinson had been targeted because “he was far too aggressive. I guess he wasn’t getting old enough fast enough for the people in that area.”

Ragsdale, a civil rights icon from Dallas and one of the first Black people elected to the Texas Legislature since Reconstruction, compared Robinson to Martin Luther King Jr. and said he believed that Robinson possibly was the victim of a political assassination. He told reporters that there was talk in Palestine that the slaying may have been carried out by a hired killer ordered to make the murder look like a suicide to avoid creating another martyr for the civil rights cause.

As word spread, condolences from across the nation and from the civil rights community were sent to Dorothy, including a telegram from Coretta Scott King, an advocate for Black equality and King’s widow.

Robinson’s death brought unwelcome attention to Palestine. “The out-of-town news media has done the city of Palestine a great injustice,” Chief Berry told a reporter from UPI on October 26, 1976. “We have been depicted as being a hotbed of prejudice and oppression of minorities. Nothing could be further from the truth.”

But Dorothy Robinson, along with other Black members of the community, objected to the white police chief’s appraisal of Palestine as a racial utopia. In fact, Palestine was an unreconstructed community of the Old South that had in the past enforced Jim Crow and still openly suppressed Black voting rights, which was what Frank was fighting against when he died.

On October 27, the Palestine court received a letter written by Robert Harding, a prisoner at the Coffield Unit, which is also in Anderson County. Harding stated that he knew who was responsible for Robinson’s murder. That same day, Texas Ranger Bob Prince went to the prison to question Harding. The prisoner said he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan and was told by the imperial wizard that Robinson was an agitator and needed to be eliminated.

But Harding lacked personal knowledge about Robinson’s death and also had a history of making false claims. The Ku Klux Klan connection went uninvestigated.

At the time of his death, Frank Robinson was deep in the planning of a meeting of the East Texas Forum to be held the following month to discuss strategies to elect more Black candidates. He had already printed the tickets for the “Second Annual Leadership Convention.” Workshops and seminars on political organizing, voter registration, and running for office were planned for November 27 in Palestine.

It never happened because of Frank’s death.

Frank James Robinson was born in an area known as Mud Creek in the rural church community of Antioch in Smith County on June 5, 1902. He was the oldest of ten children. When Frank’s mother died in 1914, he had to quit his schooling in the seventh grade to work on the family farm.

That might have been the end of Frank’s education except for what happened on a day he was making a charcoal delivery in the city of Tyler. “And he said, he heard such joy and laughter up on the hill. And he wondered what everybody was so happy about. And he asked the lady who was buying his coal what’s happening up there,” Dorothy later recounted.

His customer told him about Texas College, a historically Black college established in 1894, and Frank decided to enroll.

Initially, he was told they would accept him in their high school classes if he agreed to milk the school’s cows and work the garden. The administrator’s wife took a special interest in Frank and tutored him. When the administrator moved on to lead Prairie View Normal and Industrial College (now Prairie View A&M University), Frank took the examination for college freshmen, passed, and went with him.

It was at Prairie View that Frank fell in love. “We met in the summer of ’27. He was working washing dishes. I was waiting tables,” Dorothy said.

“Our first date was July the fourth. At the end of the school term in early August, he said, ‘I want you to be my wife.’ I was just 18. He was 25.”

Their wedding took place in a small Ford coupe car under a tree on a dirt road outside the town of Hempstead.

“I told the preacher when he read our ceremony, ‘Don’t tell me to obey Frank, ’cause I may not obey and I’m not gonna sit up here and swear that I’m gonna do it.’ So he left it out,” Dorothy said.

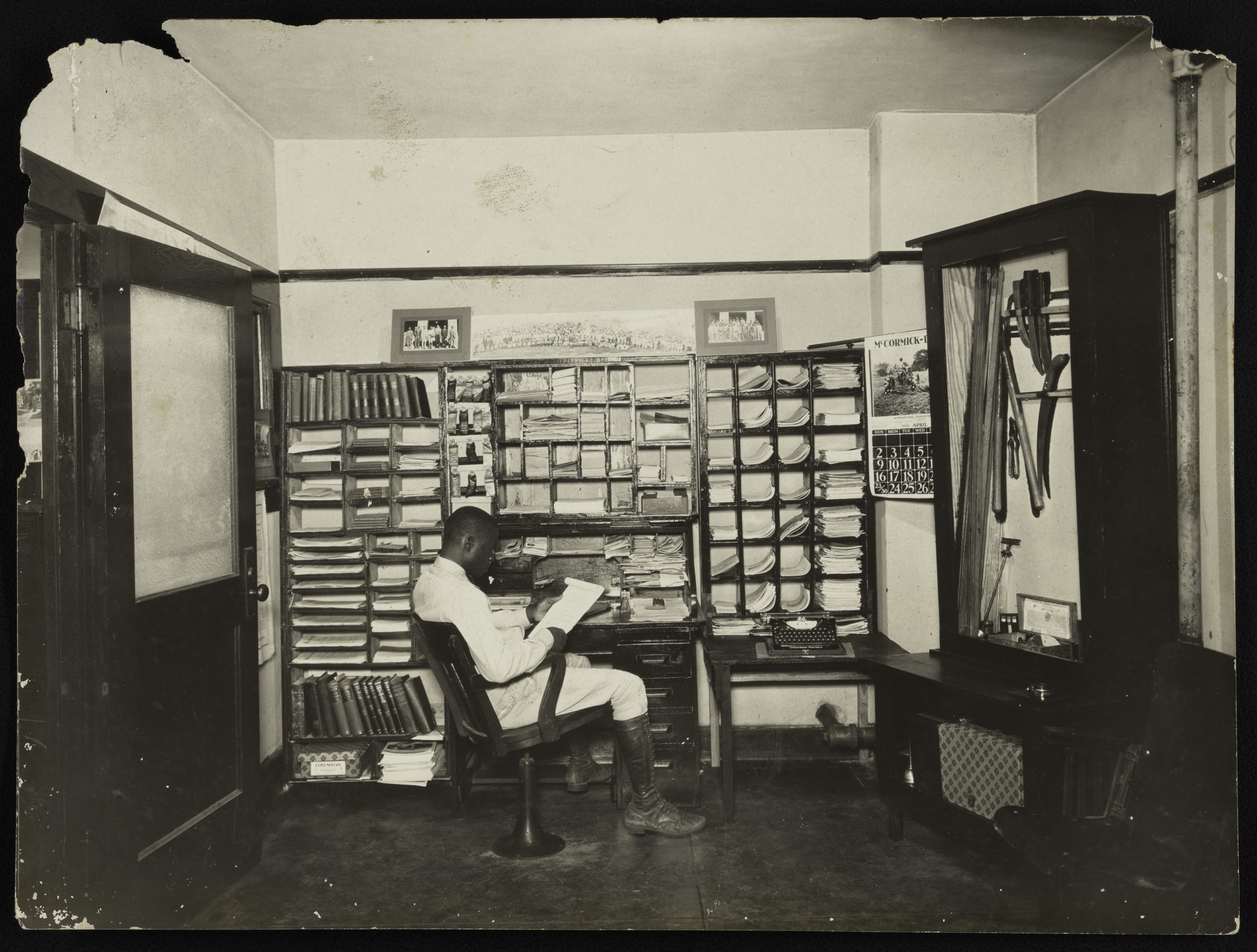

Frank graduated from Prairie View in 1931 with a bachelor’s degree in agricultural science. He went to work in Palestine, the Anderson County seat, as the county agent serving Black farmers. Frank was given an office in the courthouse basement.

That’s where the Robinsons’ 46-year marriage and their many struggles and adventures began.

“I would have married him a thousand times,” Dorothy said.

The proper pronunciation of the East Texas city is Pal-a-steen—not Pal-a-stine. Locals don’t like to be confused with the Israeli-occupied lands of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.

Today, Palestine has a population of nearly 19,000. At the time of Robinson’s death in the 1970s, it was about 15,000. Then as now, the population was at least 25 percent Black. But for most of Robinson’s life, Blacks had little or no representation in local politics.

In her memoir, The Bell Rings at Four: A Black Teacher’s Chronicle of Change, Dorothy recounts the racial discrimination she and Frank faced in their married life.

In 1944, Frank and Dorothy were riding the Sunset Limited of the Southern Pacific Railroad back to Texas from California. During the long journey, they were denied access to the dining car because they were Black. They watched white prisoners of war, German Nazi soldiers, marched inside for hot meals.

As she ate her cold, dry sandwich, Dorothy wondered how her Black brothers, soldiers off fighting for freedom in World War II, would feel about such ongoing discrimination at home.

Anderson County was highly segregated, though Frank served as an important link between the Black and white communities. Among other roles, he served on a committee planning the county fair in an era when there was no bathroom designated for Black women at the fairgrounds. He asked about it, and the chairman said, “Let them go to the woods. That’s what they’re used to.”

In the downtown shopping district of Palestine, the only bathroom that Black citizens were allowed to use for decades was in the courthouse. “There definitely was segregation. And there were those who meant to keep it that way,” Dorothy said.

No Black person had ever been elected to political office in Palestine or Anderson County before Robinson sued the commissioners court. Because of Robinson’s victory, Reginald Browne Sr. won a seat in 1978. There has been Black representation on the Anderson County Commissioners Court ever since.

Blacks were also elected in Anderson County as justice of the peace and constable, and to Palestine’s city council only after the activism of Frank J. Robinson.

In 1976, Robinson’s most recent court victory against the city had altered the playing field for city council members, who had the power to hire or fire the police chief assigned to investigate his murder.

When Palestine police began their murder investigation on October 14, 1976, they found that the screen on the door that led to Frank’s workroom and connected to the garage had been recently cut, potential evidence of a break-in. But they found no other signs of robbery or violent disturbance in the Robinson home. The only thing out of place was Frank’s black-framed eyeglasses left neatly folded on top of a filing cabinet in his home office. Robinson normally wore those glasses.

The police fixated on the shotgun found beside Robinson’s body. The old, Stevens-built Ranger shotgun had a portion of the barrel sawed off but was still legal at 22 inches long.

Police settled on the theory that the gun belonged to Frank—ignoring evidence that it may not have been his gun at all and disregarding the theory that someone else could have killed Frank with his own gun.

Dorothy told police she had never seen that shotgun before. She knew Frank once owned a shotgun that had belonged to his father, but she assumed that the dilapidated shotgun was inoperable. Police said an unidentified friend examined a photograph of the shotgun and said he thought it might be the same gun that Frank had once shown him. Frank’s brother-in-law said it was not Frank’s.

Nevertheless, Palestine police officers decided it was Frank’s shotgun.

Thus they, and in turn the newspapers, now declared his death a suicide.

Dorothy argued vigorously from the beginning that Frank would never have killed himself and could not have done so with that gun. “I don’t think Frank’s arms were long enough to shoot himself with a shotgun,” she said. She spotted other flaws in police’s suicide theory.

On the morning of the shooting, at least seven boys had been outside Story Elementary School playing football on a field next to the Robinsons’ yard and told police they heard two to four shotgun blasts.

“Why four shots? If you want to kill yourself, you don’t need but one—you’re not gonna miss,” Dorothy said. “It was definitely a cover-up deal.”

There were three spent shotgun shells in the garage and another along the fenceline at the back of the property near the schoolyard. The shotgun had been fired at a canvas mulch bag next to a tiller in the garage and also into the front-left fender of Dorothy Robinson’s car, a red 1976 Oldsmobile.

A Texas Department of Public Safety crime lab tested and confirmed that the shotgun shells were indeed fired from the shotgun found beside Frank’s body.

At the very least, the multiple shotgun blasts seemed strange and a possible sign of foul play—perhaps a struggle or a chase.

There was another oddity that perplexed some investigators: A mechanic had delivered Frank’s car and parked it in the driveway at the entrance to the double garage a few hours before his death. But police found it inside the garage. Curiously, its exterior was clean. Had it been in the garage at the time of the shooting, it would have been hit with the spray of blood and brain matter from the shotgun blast, some believed.

Chief Berry, once so sure this was a homicide, now told reporters that it was normal for someone who was going to shoot themselves with a shotgun to fire it several times before turning the weapon on themselves to make sure the weapon was working.

Today, James Todd, a current justice of the peace in Anderson County, says that in his experience, a suicide with multiple gunshots preceding the fatal shot is not at all common.

There were other unusual elements of Robinson’s case.

There was no suicide note.

Latent partial fingerprints were found on the shotgun, but investigators couldn’t match them—not even to Robinson. Officials said because of Robinson’s age, his fingertips didn’t produce enough oil to deposit fingerprints with defined ridges.

And there was no gunpowder residue found on Robinson’s hands or clothing, which is peculiar seeing as police claimed he fired the old shotgun four times.

The weapon is identified in a Texas Rangers report as a break-action shotgun, in which the barrel is hinged and opens for the manual loading and unloading of shells.

This means that after the first two shots, Robinson would have had to open the shotgun barrel, remove the spent shells, and insert fresh ammunition before firing again.

Furthermore, because there were four shots fired and police found another unfired shell in the shotgun, it must have been reloaded at least twice.

One witness was 11 years old and playing with his schoolmates when he heard the shots. The Story Elementary School students were playing football in a field next to the Robinsons’ house. He remembers that at first it sounded like lumber being dropped but then he recognized it as a shotgun blast.

“A bunch of us had skipped lunch to go start playing football, and we saw a white van pull up. We all were kids of hunters. So I grew up hunting and we know the sound of gunshots and there were gunshots and then people ran out and we testified to that,” he said, 48 years later.

He said he remembers the event as a murder.

The account of hearing four shots was told to investigators by seven different boys. Three of those boys told police they saw two white men at the Robinson house, and then saw the fleeing van. The elementary school was integrated; six of those boys were white and one, Carlos Aaron Sepulveda, was Hispanic. He was 12 years old at that time and still lives in Palestine.

“We just heard a gunshot go off and basically that’s it,” Sepulveda remembers today. He remembers only hearing one shot but in 1976 he told the investigating Texas Ranger he heard four shots. And he never saw any suspicious activity.

Sepulveda said the Robinson house was built on a little hill that overlooked the makeshift football field and Story Elementary. (The school building was destroyed by a tornado in 1987.)

This gave the boys a clear view of the house and garage. And they knew who the Robinsons were because Dorothy was a schoolteacher who taught Sepulveda’s brother.

The most detailed observation of the white van came from 11-year-old Michael Kevin Peterson, who told investigators it came out of the Robinson driveway “real fast.” It had a muffler that was smoking “real bad” and a radio antenna mounted on the front left.

In the years following, Dorothy would wonder about that mysterious van the boys saw. She would allege it was a lead that investigators never fully pursued.

Beyond the shaky physical evidence, more subtle clues point away from suicide.

For example: In Frank’s pocket was a blood-stained list of clothes he planned to buy for the coming winter. Dorothy considered that list so significant that she kept it for years.

“This is what I know, Frank James Robinson would never have killed himself. He was too busy and too involved in what he was doing,” Dorothy said.

The day that Frank’s life ended, he showed no signs of distress or despondency. First thing that morning, he walked to the post office and then to the East Texas National Bank. He spoke with Mary Kay Alexander, an 18-year-old bookkeeper, and asked her to mail him information about his checking account.

Alexander told police she remembered her exchange with Robinson and said he was soft-spoken and seemed neither jovial nor depressed.

Indeed, Frank Robinson had no reason to worry about money. He had worked as an extension agent and then an educator. He was also active in real estate development. His finances, later examined during the inquest, were sound. His house was paid for. He had several thousand dollars in the bank as well as other investments. Both he and his wife were drawing monthly pensions of $235 in addition to Social Security.

Nor did Frank Robinson have any known health problems that could have prompted him to kill himself, though he had suffered a stomach ulcer and been hospitalized for treatment weeks before his death. During his autopsy, no cancer or serious health conditions were uncovered.

Within weeks, the public furor surrounding Robinson’s death had become increasingly uncomfortable for the leaders of Palestine. Certainly, white politicians and city officeholders had a lot to gain from ruling it a suicide. Being labeled a hotbed of racial injustice was bad for business. Suicide would not only solve the problem of having to further investigate the murder of a slain civil rights leader, but it would also paint him with a stigma that might dull his voting rights accomplishments in the Black community.

But in October 1976, the elected Justice of the Peace Floyd Hassell determined that the numerous inconsistencies and the conflicting evidence prevented a routine determination of cause of death. He called for a rare legal proceeding: a public inquest.

An inquest is similar to a trial in which evidence is presented to a judge, or as in Robinson’s case, a six-member jury. The jury would decide if the evidence was sufficient to rule Robinson’s death a suicide, homicide, or inconclusive. In these cases, the jury is not held to the standard of “beyond a reasonable doubt,” but rather to the lesser “probable cause.”

On November 15, 1976, a month after Robinson was found dead, the inquest jury was sworn in. It included two Blacks, a fact seen as critical in creating the appearance of racial fairness in the controversial process.

A public inquest was so rare that no one knew how to conduct one, Alexander Nemer II recently said. Nemer was appointed to be the presiding judge of the inquest because he was an attorney and the justice of the peace wasn’t. Officials could have brought in a judge from a different county but, without explanation, didn’t. Nemer, who was the Anderson County attorney-elect at that time, called Texas Attorney General John Hill and asked him to send his smartest attorney for assistance.

Assistant Attorney General Anthony Sadberry, who was Black, was dispatched to Palestine.

Dr. Jack Pruitt, a pathologist from Lufkin, testified at the inquest that the gunshot wound that killed Robinson was “consistent” with other suicide victims he had examined. Pruitt said the angle of the shotgun blast that sheared off the top of Robinson’s head, plus other evidence, led him to believe it was a suicide.

The shotgun that killed Robinson had been pressed against his forehead above the bridge of the nose when it discharged pellets upward into the right side of the brain, Pruitt said.

But when pressed by Sadberry, Pruitt said it was “possible but not probable to me” that someone else could have shot Robinson.

“Somebody, unless this person was unconscious, would have to let this be done on purpose or think the person [with the gun] was bluffing for this to happen,” Pruitt said. “The reflex would be to pull away.”

Pruitt said that because of the nature of the gunshot wound, it was impossible to say if Robinson had been struck unconscious before being fatally shot.

Another expert witness, Cecil Kuykendall, offered a different view of the gunshot blast. Kuykendall was a former employee of the Harris County Medical Examiner’s Office and a former Palestine police officer. He told the court that the manner of death caused by the shotgun blast that blew off the top of Robinson’s head was duplicated in “very few” suicide cases he had seen. He said most suicides are performed with the gun barrel either under the chin or inside the mouth. Both methods “leave little room for doubt” as to their success.

Eleven-year-old Michael Kevin Peterson, who attended Story Elementary School the morning of the shooting, took the stand and told the jury that he heard the shots and then saw a white van in front of the Robinson home.

Civil rights attorney Dave Richards, who still lives in Austin, was there to represent the Robinson family in the inquest pro bono. He remembers the bravery it must have taken for the Peterson family to stand up in that charged atmosphere. “I was astonished that a white couple in Palestine would be willing to bring their son forward. And we put him on the stand,” he said. “But that testimony was not what they wanted to hear, so it was pretty much ignored,” Richards recalled years later.

Richards, who is former Governor Ann Richards’ ex-husband, had represented Frank J. Robinson two years earlier in his successful anti-gerrymandering case against Anderson County. Richards said the Robinson death inquest courtroom was “full of people” and at times had a circus-like atmosphere.

“The county put on what we thought was a bogus psychiatrist who testified that the pattern of Robinson’s behavior was very indicative of a suicide, based on nothing.” Richards said the psychiatrist had never spoken to Robinson. But that didn’t prevent him from testifying that Robinson was in a mental state that would lead to suicide.

Richards vehemently disagreed: “It strikes me as awfully unlikely, from what I knew of Frank, that he would have committed suicide.” Richards remembers him as “quiet-spoken and thoroughly committed to the issue of civil rights for African Americans.”

The inquest lasted four days. There were 35 witnesses. It took the jury about an hour to issue their unanimous decision: Frank J. Robinson killed himself.

Judge Nemer polled the jury twice and they didn’t waver. After dismissing the jury, Nemer pleaded with the spectators and the community to accept the decision. “To those who do not agree with the jury verdict, I can understand and sympathize with your feelings,” Nemer said.

Nemer, now 72, still insists that the jury got it right. “There is no doubt in my mind,” he said.

Nemer says he was friends with “Mr. Frank,” as he called him, and if Robinson was murdered, he would have wanted that fact to be made public.

But then why did Frank Robinson commit suicide? Nemer has no answer. “Sometimes people just kill themselves,” he said.

Forensic science has come a long way since 1976. A fresh look at the Robinson autopsy, an inspection of the physical evidence, and an examination of the crime scene photographs today could reveal clues overlooked almost 50 years ago. Perhaps some long-lingering questions about Robinson’s death could be answered.

But the autopsy, crime photos, and evidence have all gone missing.

Nemer remembers that one photograph convinced him it was suicide. It showed Robinson’s body on the floor, blood everywhere, and a cat licking the inside of his skull. “Once you see that, you never forget it,” Nemer said.

Requests to the Palestine Police Department, the Anderson County District Attorney’s Office, the Anderson County Sheriff’s Office, and the Anderson County District Clerk’s Office have failed to find any paperwork from the Frank J. Robinson death investigation or inquest. Records from 1976 are lost or no longer kept, was the agencies’ general response.

Only the DPS has been able to produce records of the Texas Rangers’ investigation. The reports are detailed but do not contain the autopsy report or the crime scene photos.

The outrage over Robinson’s death didn’t stop after the inquest. The nagging inconsistencies and unanswered questions were too incongruent to sweep away. In an attempt to help satisfy those who still insisted Robinson was politically assassinated, Texas Attorney General John Hill ordered the state’s premier forensic examiner, the Southwestern Institute of Forensic Sciences at Dallas, to prepare a full report reviewing all the pertinent evidence.

In a letter dated January 18, 1977, Sadberry, the assistant attorney general, wrote to Dorothy Robinson with an update about the continuing investigation and the new forensic review by the independent pathologist. On October 28, 1977, the Houston Post reported that the Institute’s report was completed and had been submitted the previous June to the state attorney general’s office.

Charles Petty of the forensic institute said he was told by Hill’s office to keep the report quiet and that any release to the public would come from the AG’s office. But it was never made public.

In 1982, Sadberry told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram the report had been inconclusive. It didn’t prove that it was a suicide and it didn’t prove that it was murder. Sadberry never forgot the Robinson case. He said from time to time he would page through the case transcript and wonder if the ruling of suicide was justified. “Frankly, I’m kind of uneasy about it. We just don’t know,” he said.

Sadberry died in 2008 after a distinguished law career and serving as the executive director of the Texas Lottery.

He wasn’t alone in being haunted by Robinson’s death. Into the 1980s Anderson County Sheriff Roy Herrington kept the case open and said, “I haven’t dropped it.” John Hannah, then U.S. attorney in Tyler, reopened the case after being prodded by Dorothy Robinson. He spent two years reviewing the evidence and chasing down leads before concluding there wasn’t enough evidence to indicate that Robinson was murdered.

Today, multiple open records requests to the now-renamed Dallas County Southwestern Institute of Forensic Sciences for a copy of the final Robinson report have resulted in claims the report never existed.

When pressed for details about how this report could be missing when other records from the 1970s are available, Dallas County’s response was: It appears this report was never ordered since there is no record of it in the “logbook.”

Normally, any out-of-county autopsy report would be returned to the justice of the peace in the county with jurisdiction. Though there is no statute of limitations on murder, nothing requires any Texas justice of the peace to retain death investigation records—and the current justice in Palestine does not have those records, either.

Requests for the copies of the case and inquest records were submitted to the Texas Archive, which maintains the files from Attorney General Hill’s tenure. But so far, archivists have turned up no records. According to the archive’s staff, the attorney general’s office files from this era haven’t been digitally processed and they need case numbers to locate them.

Dorothy never gave up. She wrote letter after letter to the FBI, to U.S. Senator Lloyd Bentsen, to state leaders, and anyone else she thought could help reopen the case, reclassify Frank’s cause of death, and bring his killers to justice.

“It was February before I even got a death certificate. The death certificate got lost. The records got lost, something happened and something happened,” she said. “And then, when I did get the death certificate and I had to sign whatnot for it, that was when I really broke down because it said ‘death from a self-inflicted, massive, massive wound.’ And I knew Frank Robinson did not kill himself. I cried like a baby.”