France's main Braille publisher is in financial crisis after a bold decision to sell its embossed books for the same price as standard ones. Its future raises the broader question of whether printed Braille still matters in the digital age – as its staff and visually impaired volunteers believe it does.

2025 marked the 200th anniversary of Louis Braille's invention of the six-dot tactile writing system that opened the door to literacy for millions of blind people.

Two centuries on, Braille is still used by around a third of France’s estimated two million blind and visually impaired people.

Yet access to reading material remains limited. Of the roughly 100,000 books published in France each year, only about 3 percent are transcribed into Braille. And just one institution systematically follows contemporary literary trends – the Centre de transcription et d’édition en braille (CTEB), based in Toulouse in south-west France.

Founded in the late 1980s, following earlier research into Braille transcription software at Toulouse University, the CTEB became France’s main centre for transcribing, editing, printing and distributing Braille books, magazines and documents.

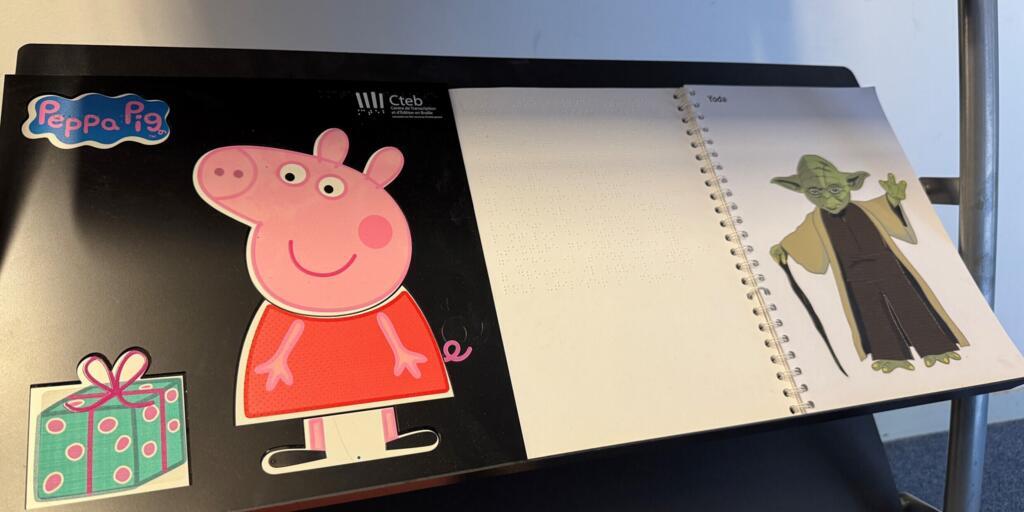

Today its catalogue contains around 2,000 titles, with between 200 and 250 new books added each year – from Harry Potter and Disney stories to self-help manuals and recent literary prize winners.

“Our collection has books for children from the age of four. And then it’s really all styles,” says CTEB director Adeline Coursant.

“Thrillers, novels, biographies, but also practical books like recipes, computing… We even produced the first books on sexuality, with illustrations in relief, which didn’t exist before. So there’s a bit of eroticism. And the current trend is towards personal development, spirituality and so on. So we keep abreast of the latest literary trends.”

Listen to a report from the CTEB on the Spotlight on France podcast:

A costly endeavour

Producing books in Braille is expensive. They require around three times more paper than standard editions, and the paper itself is more costly.

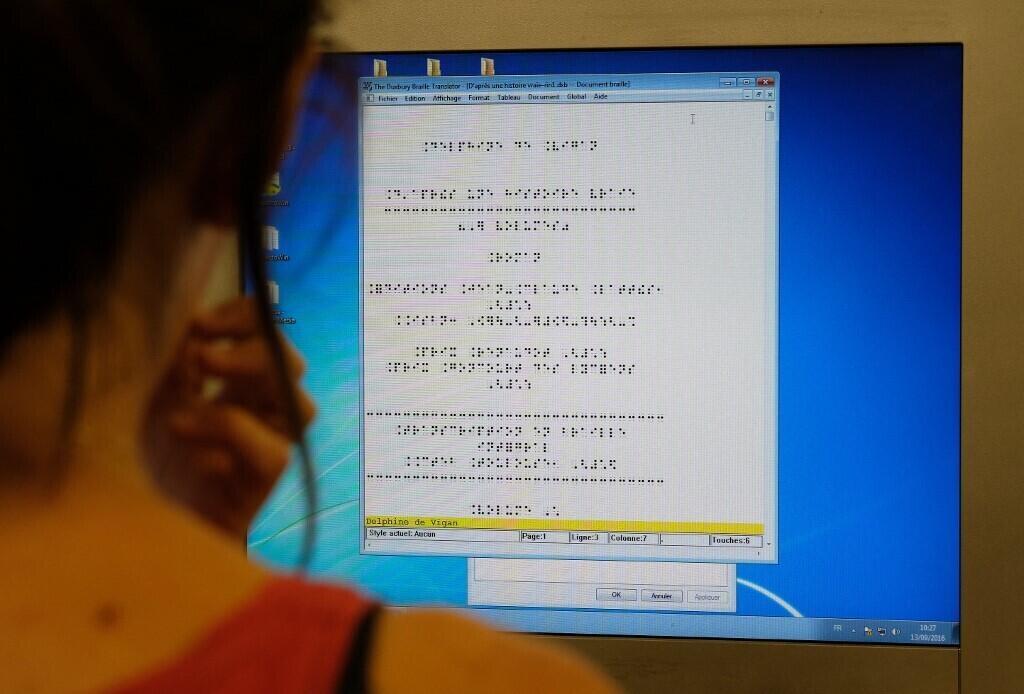

The process is also labour-intensive. Texts must be cleaned, page layouts simplified, and illustrations redesigned before transcription using specialist software.

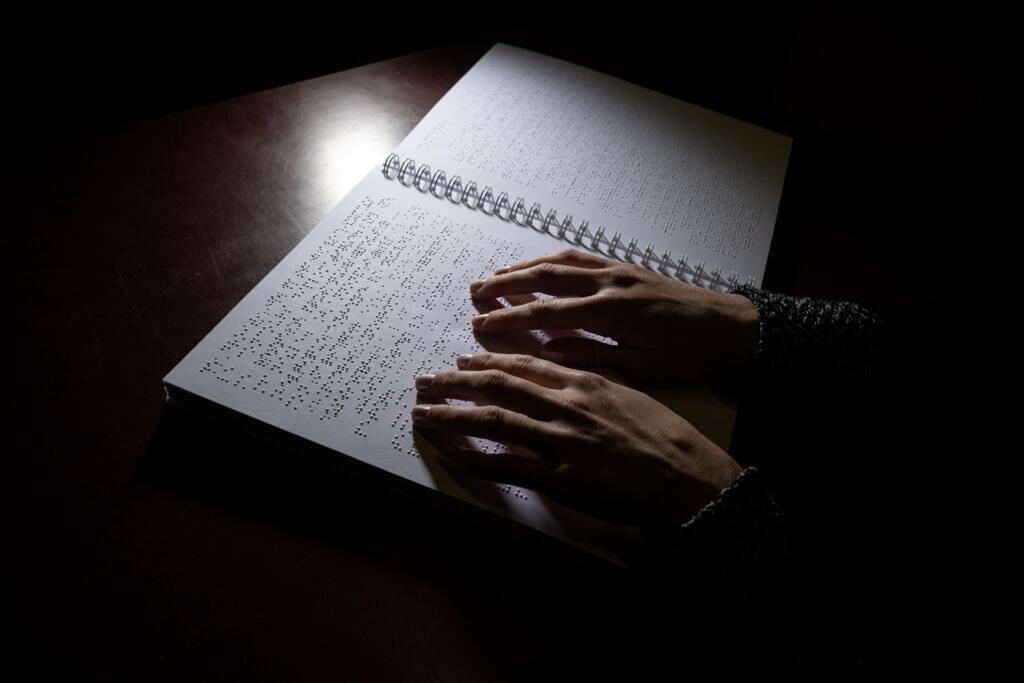

Every letter and character of the transcriptions are then checked by the CTEB's reading committee of blind volunteers.

“I'm re-reading the books, testing the transcription," says 42-year-old Sophie Renault, who recently joined the 60-strong team.

She works in tandem with her friend Virginie, touching the design of the books the graphics department produces "to see if they are compatible or accessible for blind people and how they can be improved".

The pair have different, but complementary, profiles. "I was born blind so I'm very bad at mental and spatial representation. Virginie is very good at manual things."

Given all the additional work involved, the average cost of producing a Braille book is between €700 and €900. And for children’s books where intricate details of the illustrations have to be rendered tactile, the price can rise to €1,500.

“We adapt all the drawings in the books so they’re understandable to the touch, while retaining the original illustrator’s style,” Coursant says. “You can’t ‘see’ a character in profile on a drawing… so we have to rework all the drawings.”

French woman allowed to daydream again thanks to guide dog

Service providers

Alongside books printed out on large machines known as embossers, the centre also generates its own revenue by producing Braille versions of bank statements, tourist brochures, theatre programmes, festival guides and newspapers.

Agnès Cappelletto, one of the centre’s 12 employees, is in charge of transcribing and editing such documents. After receiving the PDF versions on her computer, she uses Duxbury software for the transcription into Braille and then prints them off page by page from a small embosser on her desk.

Today she's processing an order for a Braille version of a lengthy Christmas Eve restaurant menu from a customer who wanted her blind father to be able to read what he would be eating.

"They can read the menu separately and discuss it afterwards," Cappelletto says. "It wouldn't have been the same experience for the father if his daughter had had to read the menu to him.

"I like being of service to people," she adds.

Making movies accessible to blind people

Paper vs digital

Given the high cost of producing Braille books, and with audio books and digital Braille available at a fraction of the cost, some question whether paper Braille has a future.

Renault is very digitally connected and says she accesses Facebook, WhatsApp and YouTube on her phone, using a voice-activated screen reader. Even so, she recognises it's not for everyone.

"I prefer to read on my computer, but people still need to have paper Braille. It’s like you, when you 'see'. Some people need to have the book in their hand. Some people like turning pages."

For CTEB president Blandine Gallo, who lost her sight at the age of six, it's not just a matter of preference. Paper Braille helps people, not least children, to become literate, she argues.

“Many people oppose paper Braille and digital Braille, but we shouldn't pit the two against each other, we need both,” she says. “We need paper Braille because it’s important to have the knowledge of the page, with the lines, with the end of the line. Children who have never 'seen' can’t know how a book is organised."

While audio and digital Braille books have their place, she says paper Braille remains crucial for learning spelling, grammar and spatial organisation – skills that underpin literacy and encourage independence.

Cricket World Cup for blind women helps change attitudes

Equality at a price

Until recently, the CTEB sold Braille books to libraries and bookshops at roughly three times the price of the original, reflecting their greater length and production costs. But in January 2023, Coursant decided to apply France’s fixed book-pricing law, introduced in 1981 by then culture minister Jack Lang.

The institution, which used to sell works from its catalogue between €60 and €122, began pricing them between €11 and €30.

“It’s about equality,” she says. “There’s no reason why a blind person should have to pay three times more because they have a disability.”

The centre is now operating at a considerable loss. “On average, we’re losing €680 per book,” Coursant explains. With up to 250 titles a year, that amounts to more than €130,000 annually. The cumulative funding gap now stands at €300,000.

“We’re in difficulty because we’re not supported enough,” she says. They've requested funding from the culture ministry but despite promises, it has not materialised.

“We’re not asking for a huge sum, €300,000 a year. It would allow us to supply not only all blind people in France, but also all French-speaking media libraries.”

Coursant has also floated a novel idea: adding a ten-cent solidarity contribution to every book sold in France to fund accessible publishing for people with disabilities, including those with dyslexia or who just need larger print.

The CETB sent all of France's MPs and senators a card in Braille this Christmas, drawing attention to their cause. As Coursant says: "It's time the state considered blind people as French citizens."

Listen to a report from the CTEB on the Spotlight on France podcast, episode #137.