I’ll do the remembering myself, letting it make of me what it will as memory does, with its own moonlit trail, bread crumbs, peril, revelation.

—Susannah Sheffer, “After: An Introduction”

In 2008, just after college, I spent the summer traveling across Texas in a midnight-blue Corolla with a crooked “Yes We Can!” Obama bumper sticker. I’d been hired by a new organization called the Texas After Violence Project, founded by Walter Long, a veteran capital defense attorney who could no longer stand to watch people destroyed by trials, death sentences, years of appeals, and eventually, executions. His idea was to use oral histories to reveal the widespread traumatic impacts of the death penalty on the loved ones of people sentenced to death, the loved ones of murder victims, defense attorneys, prosecutors, jurors, and corrections officers. Walter wanted to open space for people to share their experiences with the death penalty in their own words, on their own terms. He hoped that building an archive of stories that showed the destruction the death penalty caused in every life it touched would urge Texans to confront the impacts of our deep-rooted love for revenge and retribution.

The Corolla’s driver was the organization’s first director, an activist and lawyer named Virginia Raymond, who taught me that summer how to listen deeply with empathy and compassion to people as they recounted their experiences of loss and survival. Virginia often reminded me that, in documenting these stories, we weren’t just documenting facts; we were documenting what literary critic Shoshana Felman called “fragile evidence”—testimony of tragedy and suffering that carries the power to imprint collective memory.

That summer, we conducted several interviews a week, sometimes two in one day. Our first interview was with the father of a young Black man executed for murdering a prominent white businessman in East Texas. He told us about how the white prosecutors described his son as a predator hunting his victim. How the all-white jury, including a juror who was president of the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, sentenced his son to die. How, on the day of the execution, the family prayed unremittingly until the U.S. Supreme Court denied their final appeal. How, after the execution had been carried out, he reassured his family that God had not failed them. How his wife became very ill. And how, after he was laid off from the steel plant where he’d worked for over three decades, he had to take a job as a night guard in the same prison system that killed his son so that he could get health insurance.

After the interview, I sat on the patio with the man, drinking iced tea and continuing a conversation we’d started that morning about the philosophy classes I’d taken in college. He was particularly interested in my metaphysics classes. Perhaps he’d been wondering, Was there a reality beyond the one he’d been living? Could reality be altered, rearranged, undone?

As the fiery sunset dissolved into night, I tossed the football in the backyard with the man’s young grandson, maybe 4 or 5 years old, and couldn’t help but wonder what his life would be like growing up in this little town. In this state. In this country. That night, I’d sleep in a room on the second floor of the family’s home and wonder if the condemned son had ever slept in this room, staring at the ceiling like me. Wondering what might become of his future.

The next day, we traveled to Huntsville to interview the man’s other son, who was only 10 years old when his brother was sentenced to die. He wanted to do his interview outside the high red-brick walls of the prison where his brother was executed, but the guards with shotguns in watchtowers peering down on us made us uneasy, so we opted for the public library down the street. Like his father, it was clear that he’d also struggled to make sense of what happened to his older brother. Reflecting on the denial of his brother’s final appeal by the U.S. Supreme Court, in which three justices recused themselves because of their personal relationships with the victim’s family, he said: “It’s a tie, so you lose. To me, that doesn’t make sense. … If a baseball game is tied, you go into extra innings. In Japan, if the baseball team ties, it’s a win. Why is the judicial system different?”

I was having trouble believing in justice after the stories we’d been hearing.

In June, we interviewed a defense lawyer whose client was executed even though he was so severely intellectually disabled that he didn’t understand why he’d been sentenced to death in the first place. We interviewed a woman whose brother, a prison corrections officer, had been murdered in a prison. We interviewed a woman whose adopted son was executed for raping and killing a young woman in the same park where I played basketball every day after work. We interviewed a defense investigator who could not get the image of a young girl with a gunshot between her eyes out of his head, who, one day while jogging, saw a hole in the sidewalk filled with small rocks and had a panic attack.

We interviewed journalists who witnessed executions and described how the condemned prisoner is already strapped to the gurney when the curtains in the death chamber swing open. How a boxing ring–like mic hangs from the ceiling to amplify the final words. How the warden removes his glasses to signal to the hidden executioner to start the lethal chemicals. How the chaplain rests his hand on the ankle of the condemned. The journalists variously described the death rattle—the sound of the condemned dying—as ragged breathing, a loud snore, a horrible choking sound, a bag of coins shaking.

Virginia and I drove 500 miles from Austin to Amarillo to interview a Catholic bishop about an elderly nun who’d been raped and murdered on Halloween night, 1981. We stopped at a panaderia on the way, where, over Mexican Cokes and empanadas de calabaza, I told Virginia that I was having trouble believing in justice after the stories we’d been hearing. I’d awoken to the ways the legal system meets violence by brutally and relentlessly perpetuating more violence and trauma across families, communities, and generations. It had become impossible to reconcile these truths with everything I’d always been told to believe about the legal system’s pursuit of justice. With every story I was hearing that summer, another fragment of the worldview that had painted my life up to that point fell away. The worldview of the brown kid who raced around the neighborhood with red and blue police lights on his bike. The worldview of the brown man who has escaped the bullet, the cage, the needle.

Virginia told me that justice must exist, or else what is there to wake up every day and fight for? I needed her calm assurance. I needed to believe her. As we were leaving the panaderia, Virginia turned to me and warned me not to dwell too much on the stories we were hearing. Otherwise, she said, you’ll drive yourself crazy. I nodded, and we walked out into the hot swirling wind.

The bishop welcomed us into his modest home near the diocese and told us the story of the Swiss nun who’d arrived at the St. Francis Convent after a missionary trip. How they’d found her on the floor next to her bed, stripped and bloodied, after she hadn’t shown up for morning Mass, and how the nuns still keep a candle burning in her room. Four years after the murder, police arrested a local boy, 17 years old, who lived across the street from the convent. The boy insisted he was innocent, but the prosecutor charged him with capital murder and the jury sentenced him to die. For many years, the bishop and the nuns fought to spare the boy’s life. Pope John Paul II appealed to Governor Ann Richards, who granted a temporary reprieve before allowing the execution to proceed a few weeks later.

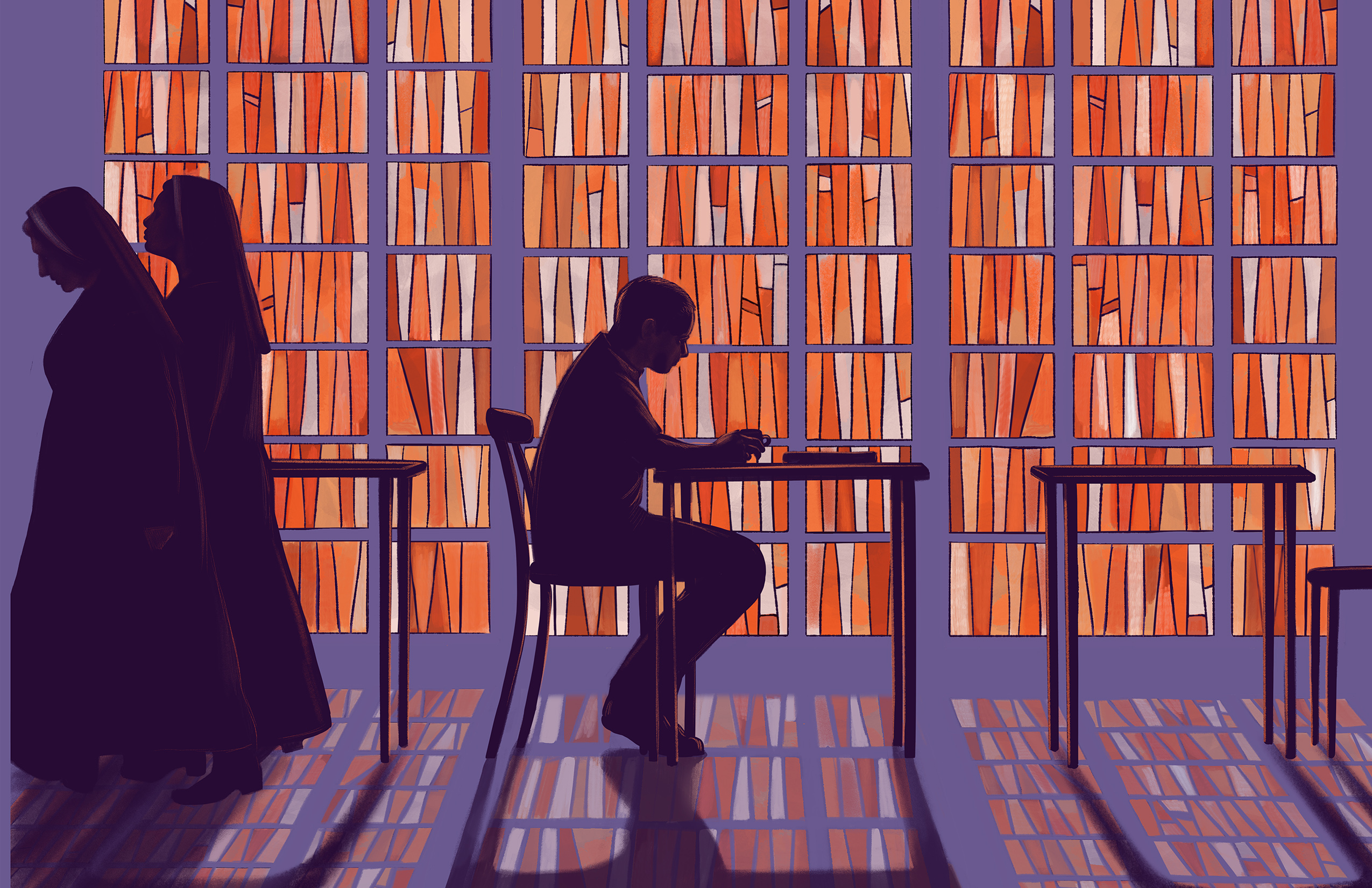

After the interview, the bishop invited us to have lunch at the convent. In the silent cafeteria polygon, light emanated from a stained-glass window, bestowing bright geometrical blessings on the nuns sitting below, heads bowed, slurping soup. “That one found the sister that morning,” the bishop told us, pointing out nuns with his spoon. “That one knew the sister, too. That one was never the same after that day.”

By August, it was becoming clear to me that there was no escaping the stories. When we weren’t on the road conducting interviews, we were at our office reflecting on them, preparing them for the archive, preparing for the next one.

Every morning, when I’d walk into the office building and see the fake dracaenas near the elevator and smell the overpowering potpourri air freshener, my heart would begin to beat faster and my hands would become cold and damp. We’d sit in front of our computers for hours transcribing the interviews. Watching the videos over and over again. Pause. Slow down. Rewind. Speed up. Repeat. Their trembling voices, their eyes. The lines cutting across their faces, pulled down by the gravity of grief and sorrow.

Oral historians are supposed to be silent observers. Disembodied voices on the recording. But even something as mundane as repeatedly transcribing the first-person “I” can begin to play tricks on the mind, blurring the boundaries between self and storyteller. Soon you start to catch glimpses of yourself in the stories. In the police car. In the courtroom. In the death chamber. At the funeral. Soon apparitions of suffering appear like mirages in the desert of one’s memory. It isn’t real, but it is. It is you, but it isn’t.

As the summer heat intensified and patches of burned grass on the side of the highway passed with more frequency, we drove to Burleson, just south of Fort Worth, to interview the parents of a man executed for killing five people during a psychotic breakdown. The cream-colored walls of their home were filled with ethereal landscapes sent to them by men on death row whom the elderly couple had come to know over the years they visited their son at the Polunsky Unit in Livingston.

To prepare for the interview, I spent a few afternoons at the state archives reviewing case files and came across a biographical essay their son had written while awaiting execution. He first started to “feel different” when he was in the military, he wrote. After being discharged because of a psychotic break, he moved from town to town working construction jobs and experimenting with drugs. He began to build little pyramids that he believed gave him special powers. One night, he felt a cosmic force release within him that he believed would soon end the world. On the day of the murders, he believed the souls of the dead would swallow the earth in flames.

Throughout our interview, the woman would reach between the couch cushions every so often to retrieve a Hershey’s Kiss her husband had “hidden” for when her blood sugar dipped. “He’s my savior,” she said, winking at him and sliding a chocolate into her mouth. “Daddy,” she would say to her husband, “get me some water.” “Daddy, tell that one story.” “Daddy, don’t tell that story.” For hours, they huddled in front of our camera recounting their many attempts over the years to get their son help for his severe schizophrenia. “Everybody said they couldn’t help him because he wasn’t violent, and if he ever got violent then they would commit him to the hospital,” the woman told us. “And then they committed him to death row.” This had become her battle cry, one she repeated often at rallies with the earth-shattering force of a grieving mother.

A few weeks later, Virginia and I interviewed the sister of a mentally ill man who’d been executed for kidnapping and killing a hitchhiker. He told police he’d done it because he’d hoped to return to prison, where he wouldn’t be such a burden on his family. After the interview, we rushed to a Kinko’s before it closed to make copies of photographs of his sister taken by a photojournalist. I remember feeling sick as I watched the photocopies multiply and stack in the copier tray. A photo of the sister at a flower shop picking out a wreath for her brother’s grave. Sitting in the prison parking lot taking swigs of whiskey before her final visit. Walking into the prison, smudged mascara under her eyes, to witness her brother’s execution.

I flipped through the photos again in my motel room that night as I sipped a lukewarm beer. When I came across a photo of her brother smiling on the day of his execution, my body suddenly folded as though it were being pulled to the ground by a giant magnet. My heart beat against my chest. I didn’t know what was happening. I didn’t know what to do. I curled into myself, frozen, until I finally fell asleep.

That night in the motel room in East Texas began a period of intense fear that lasted for several months. Every moment was footnoted by the knowledge that violence was happening somewhere, to someone, right then. I’d sit still for hours at a time scanning my body for signs of death approaching, obsessing over every sensation—not unlike the structuralist philosophers who debated the metaphysics of madness, if only to try to avoid being consumed by it themselves. If the healthy bodies of the condemned can be suddenly erased by a breach of nature, why couldn’t my own?

Virginia encouraged me to take some time off and registered me for a conference about self-care. In a workshop on compassion fatigue, the facilitator passed around crayons to the packed room of social workers, therapists, and paramedics and told us to draw a picture showing how we were feeling in that moment. I drew an oak tree being struck by lightning, splitting in two.

It’s a cliché straight from an old ranchera song to say I drank to numb the pain, but it’s true. That summer, I put on 20 pounds. I remember sitting alone one night in the Hill Country, deep into a bottle of cheap cabernet, in awe of the power of the stories over me. I surveyed the land, moonlit and damp from the summer rain. I remember the black shadows of cedar elms reaching toward the sky like buried memories refusing to rest.

When I finally saw a therapist after resisting for several months, she asked me if someone I was close to had recently died. I said no. She asked me if I’d experienced anxiety or depression before. I said no. When I told her what I’d been doing that summer, she put down her pen, sighed deeply, and told me I was experiencing vicarious trauma. I was grieving for the dead, she said, even though I never knew them.

Every moment was footnoted by the knowledge that violence was happening somewhere, to someone, right then.

She placed old Walkman headphones on my head and told me to close my eyes. The metronomic tones hummed as I talked about the stories I’d heard that summer. Hummed as sweat rolled down my face. When it was over, she offered to cradle me like a child, explaining that doing so could be therapeutic. I declined, thanked her for her time, and never went back.

Back then, I didn’t know anything about vicarious trauma, but I remember being immediately suspicious of its premise of distance. It was becoming very clear to me that bearing witness to stories of violence and death, whether in war zones or in living rooms, is to absorb the suffering of others. Whether it’s basic human compassion or some empathic telepathy of mirror neurons, in the moment of the story’s telling, witness and storyteller are bound together as if there is no distance between them. The story enters the witness and stays for a lifetime.

But untethered from the original violence, the pain of the witness seems baseless. Emergent from nothing. An imagined annihilation. There is guilt and shame when standing next to the pain of those who lived through it even when the texture of feeling is the same. Not only did I survive, I wasn’t even there. Who am I to suffer? Who am I to grieve? Who am I to have a story of my own?

I left the Texas After Violence Project the following summer, encouraged by Virginia to attend graduate school. Maybe she was trying to protect me, trying to get me away from the stories. The fear that death was always near eventually lost its power over me, little by little, with every bright morning I found myself staring back in the bathroom mirror.

It’s been 13 years and here I am still.

The stories from that summer occasionally return to me at seemingly random moments, and suddenly I’m back on some unending highway in Virginia’s Corolla, in some stale motel room in East Texas, in our old office staring at a video of a grieving mother looking back at me.

In 2015, Walter called me out of the blue one afternoon and asked me to return to the Texas After Violence Project as its director. I hesitated. I feared being destroyed again. But I also knew that my experience that summer had only solidified my belief in the transformative power of stories of loss and survival in the aftermath of violence. After graduate school, I’d worked on an oral history project about abuse and torture at the Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp during the post-9/11 global “war on terror.” Then I’d worked on behalf of death-sentenced defendants as a post-conviction mitigation investigator collecting stories of violence that had been done to them as children that could be used as crucial evidence in their legal appeals. Storywork in the aftermath of violence, as emotionally and psychologically punishing as it is, had become a calling.

When I walked into the office building after several years and saw the same fake dracaenas near the elevator and smelled the same overwhelming potpourri, I froze. My hands became cold and damp. What are you doing here?

In the office, I found a photo from our first interview that summer. I’m kneeling behind the video camera. I’m so young. The photo now hangs over my desk as a reminder of who I was that day and who I’ve become since. Now I understand that bearing witness to stories of loss and survival is often as giving as it is unbearable, generative as it is destructive. The stories embrace us, nurture us, obliterate us. All at once. To bear witness is to offer one’s own body as an archive of the pain of others. I can’t help but imagine what kind of world we could create if we all opened ourselves to this fragile evidence.