The study of exoplanets, worlds which orbit stars other than our sun, is currently being transformed by the new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). We will shortly gain our first insight into conditions on rocky, potentially Earth-like worlds beyond our solar system. One of these distant worlds might host life. But could we detect it?

We may be able to spot signs of life in the composition of the planet’s atmosphere. We can use a technique called transmission spectroscopy – which divides up light by its wavelength – to search for traces of different gases in starlight as it passes through a planet’s atmosphere.

Some starlight-absorbing gases might indicate the presence of life on the planet. We call these biosignatures.

1. Oxygen and ozone

Oxygen is probably the most obvious biosignature. Plants make it, we breathe it and the rock record shows that levels in Earth’s atmosphere changed dramatically as life evolved. The oxygen that we breathe is O2, two oxygen atoms stuck together. But another configuration of oxygen, O3 or ozone, could also be observed with JWST.

So, if we detected one or both of these gases, would it be job done? Unfortunately not. Another scenario that could produce large amounts of atmospheric oxygen is a planet undergoing a “runaway greenhouse effect”. Once a planet is hot enough for its water ocean to evaporate, the resulting water vapour in the atmosphere contributes to a greenhouse effect – super-heating the planet to levels that aren’t compatible with life – in a feedback loop.

Eventually, the planet becomes hot enough for water molecules to break apart into hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen molecules are light and can move fast enough to easily escape the planet’s gravity, whereas the more sluggish oxygen tends to stick around, ready to be detected and trick unsuspecting astronomers.

2. Phosphine and ammonia

The current focus of the search for life might be mostly on exoplanets, but there have also been recent developments closer to home. Phosphine – a gas that occurs naturally in hydrogen-dominated atmospheres like those of gas giants Jupiter and Saturn – was recently detected in the atmosphere of Venus. Interestingly, phosphine is considered to be a potential biosignature.

On Earth, phosphine is produced by microorganisms, for example in the intestinal tracts of animals. If no life is present, we wouldn’t expect phosphine to occur in large quantities in Venus-like atmospheres, which are dominated by carbon dioxide. That said, we can’t yet rule out other sources of phosphine on Venus.

Foul-smelling ammonia is another potential biosignature gas, also produced by animals on Earth. Like phosphine, it is prevalent on gas giant planets, but not expected to occur on rocky worlds in the absence of life.

However, detecting phosphine or ammonia in the atmosphere of a distant exoplanet is likely to be challenging. Both reach tiny concentrations of only a few parts per billion on Earth. So unless our potential extraterrestrials are much stinkier than Earth’s animals, we probably won’t be spotting them any time soon.

3. Methane plus carbon dioxide

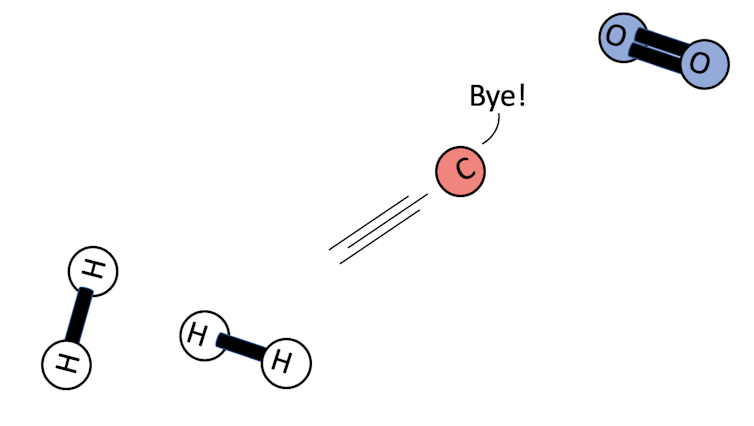

Individual gases that are unambiguous biosignatures are few and far between, so we might be better off looking for a winning combination if we want to detect life. Large amounts of methane, produced by farting animals on Earth, plus carbon dioxide would be a good hint that there is something going on.

If there’s enough oxygen available, then carbon much prefers to hang around with oxygen as carbon dioxide (CO2, one carbon atom and two oxygen atoms), rather than form methane (CH4, one carbon atom and four hydrogen atoms). In an oxygen-rich environment, any carbon finding itself in a methane molecule quickly ditches its hydrogen buddies in favour of a couple of spare oxygens.

So seeing lots of both methane and carbon dioxide coexisting would suggest that something – maybe bacteria – is constantly producing methane.

4. Chemical imbalances

We can apply the above argument to any combination of gases that shouldn’t happily coexist. Life disrupts the chemical equilibrium (balance) of its environment because it uses chemical reactions to generate energy.

On Earth, oxygen is transformed into carbon dioxide, but in a different type of atmosphere, with different chemicals available, life would use other processes to achieve the same goal. Methane-producing bacteria that live around hydrothermal vents deep in Earth’s oceans, for example, harvest chemical energy from minerals and chemical compounds. Looking for imbalances allows us to be open minded about what life elsewhere might look like.

What happens if we spots signals of alien life?

JWST is already exceeding our expectations for exoplanet atmosphere observations. As powerful as it is, though, rocky planets with mild temperatures and atmospheres dominated by nitrogen or carbon dioxide are still going to be challenging to study using transmission spectroscopy. The signals we expect from these planets are much weaker than those we have successfully observed in hot gas giant atmospheres.

If we are lucky enough to observe starlight-absorbing gases in the atmosphere of a rocky exoplanet – TRAPPIST-1e, for example – we still have to measure how much of these gases are present to draw meaningful conclusions. This isn’t straightforward as the signals can overlap and need to be carefully disentangled.

Even if we do detect and accurately measure one of our possible biosignature gases, I don’t think we could claim to have detected alien life. JWST is only just opening up a new, rich laboratory of planetary atmospheres, and as we explore no doubt we will find many of our previous assumptions are proven wrong.

Jumping to conclusions about aliens every time we find something unusual would be premature. A JWST biosignature detection would be an interesting hint, with the promise of a great deal more work to do. As an astronomer, that’s exciting enough for me.

Joanna Barstow receives funding from the Science and Technology Faciliites Council. She is a Councillor and Trustee of the Royal Astronomical Society.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.