Carbon emissions from fossil fuels are set to reach a new high in 2024, with no clear signs yet of the urgently-needed peak in pollution to curb global warming, scientists have said.

Global emissions of carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas driving climate change, need to peak and fall rapidly to zero overall if the world is to have a chance of limiting rising temperatures to levels that avoid the worst impacts of warming.

But the latest annual global carbon budget assessment has found that emissions from both fossil fuel use and land-use change such as deforestation are up on 2023 levels this year, totalling 41.6 billion tonnes, up from 40.6 billion tonnes last year.

The warning comes as countries meet in Baku, Azerbaijan, for the latest round of UN climate talks which are focusing on finance for poorer countries to develop clean economies and cope with the already-inevitable impacts of climate change, and as they gear up to submit new action plans for 2035.

Global carbon emissions from burning and using fossil fuels are projected to rise 0.8% in 2024, reaching 37.4 billion tonnes, according to the Global Carbon Project, which involves researchers from around the world.

It comes despite progress in rolling out renewables and electric vehicles, as increased gas and oil use has driven emissions up, while coal has also marginally increased, the assessment shows.

The impacts of climate change are becoming increasingly dramatic, yet we still see no sign that burning of fossil fuels has peaked

Increases in fossil fuel emissions came from aviation which has rebounded after the pandemic, from India where renewable rollout has been outstripped by increased coal use to supply more people with power, and in the world beyond the major emitters of China, US and Europe.

Meanwhile, emissions from changes to land use are also up this year to 4.2 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, with drought conditions worsening emissions from deforestation and forest fires.

There is a glimmer of hope in that over the last 10 years, while fossil fuel pollution has risen, carbon dioxide emissions from land use have fallen on average as deforestation has reduced and forests have been restored and planted.

This means that overall, total carbon dioxide emissions have plateaued in the past decade, which is progress after a strong decade of growth averaging around 2% a year between 2004 and 2013.

But Professor Pierre Friedlingstein, of Exeter University’s Global Systems Institute, who led the study, said: “The impacts of climate change are becoming increasingly dramatic, yet we still see no sign that burning of fossil fuels has peaked.”

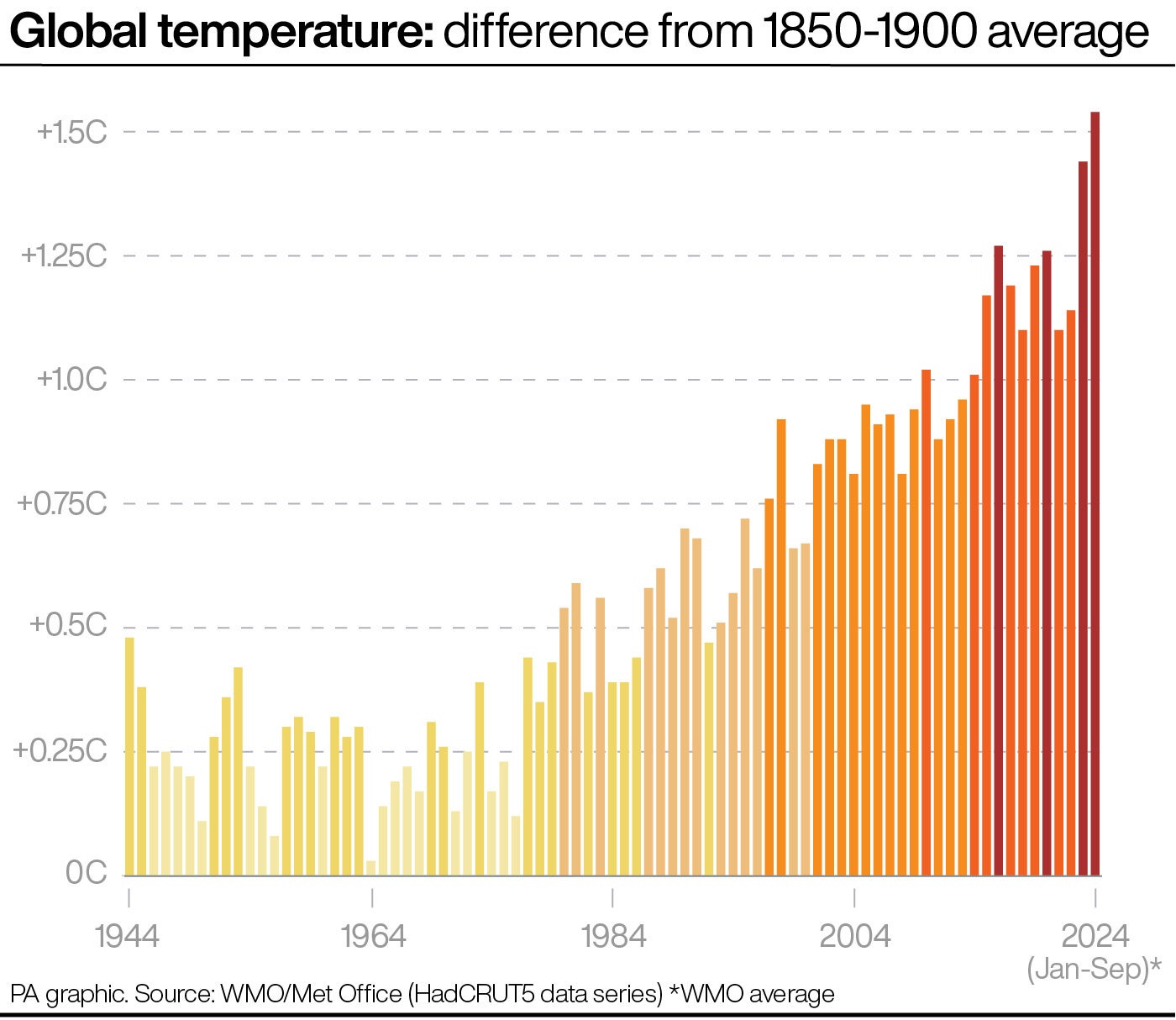

Under the Paris climate treaty, countries committed to keeping temperature rises to “well below” 2C and to pursue efforts to limit them to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels to avoid the worst climate-driven extreme storms, floods, heatwaves, droughts, rising seas and collapse of natural systems.

Prof Friedlingstein warned “time is running out to meet the Paris Agreement goals” as he warned world leaders at Cop29 must bring about rapid and deep cuts to fossil fuel emissions.

To meet the 1.5C limit, emissions would have to drop from current levels to zero by the late 2030s, he added.

Professor Corinne Le Quere, from the University of East Anglia’s School of Environmental Sciences, said: “Atmospheric carbon dioxide is now 52% above pre-industrial levels.

“It will continue to rise and cause further climate change as long as total carbon dioxide emissions do not reach net zero globally.”

But despite another rise in emissions this year, there was evidence of widespread climate action, with renewables and electric vehicles displacing fossil fuels, she said.

The researchers pointed to 22 countries, including many European nations, the US and the UK, where fossil fuel emissions have fallen during the past decade, even as their economies grow.

But Dr Glen Peters, of the Cicero Centre for International Climate Research in Oslo, said the much-needed peak in emissions was “frustratingly close, but it’s not quite there”.

“We’ve been discussing peak emissions for many years now, and it feels it has got close; renewables are growing strongly, electric vehicles are growing strongly, but still it’s just not enough,” he said.

Dr Peters said he would not be surprised if in the “next years we do get a peak and – hopefully – a decline after that”.

The study is being published in the journal Earth System Science Data as a pre-print, and later as a peer-reviewed paper.