A former detainee of the Guantanamo Bay prison camp has claimed that Florida governor and 2024 presidential contender Ron DeSantis witnessed him being tortured during the time he was stationed there.

Mansoor Adayfi, a Yemeni citizen who was held for 14 years on the US Naval base in Cuba, told The Independent in an extraordinary interview that he was brutally force-fed by camp staff during a hunger strike in 2006, and that Mr DeSantis was present for at least one of those sessions.

The United Nations has characterised the force-feeding of hunger strikers at Guantanamo Bay as torture. The US government has denied that the practice amounts to torture, and it has been used against prisoners over successive administrations during hunger strikes.

Mr DeSantis was stationed on the base between March 2006 and January 2007, according to his military records.

An investigation by The Independent details the following claims:

- Two prisoners held at the camp at the time Mr DeSantis was stationed there claim he witnessed the forced-feeding of hunger-striking prisoners.

- Mr Adayfi claims that Mr DeSantis had initially told him he was there for the detainees’ welfare.

- Mr DeSantis was stationed at Guantanamo during a year marked by riots, hunger strikes and death.

- Part of his role was to field concerns and complaints from prisoners.

- Mr DeSantis emerged from his time at Guantanamo as an advocate for its continued use, and against the release of detainees.

Mr DeSantis has not responded to several requests from The Independent for comment on the allegations and for clarity about his role in the notorious prison camp.

As an assumed candidate for the 2024 election, Mr DeSantis is likely to face questions about this time in his career and what impact – if any – witnessing the treatment of Guantanamo detainees has had on his politics.

Until now, he has not spoken in detail about this part of his career. In public, he has advocated for the continued use of Guantanamo Bay to hold detainees suspected of involvement of terrorism, but he has not spoken in detail about his time spent at the camp.

‘Bleeding, vomiting and screaming’

Mansoor Adayfi describes it as one of the worst stretches of his 14-year imprisonment at Guantanamo Bay. In 2006, he was in the midst of a hunger strike with a number of his fellow detainees in protest over the conditions inside the notorious prison. A new team had been brought in to break the strike with a more aggressive form of force-feeding. One day, he recounts with emotion in his voice, he was strapped to a chair in the yard by his head, hands, waist and feet, and a feeding tube was forced into his nose. He was bleeding and vomiting and screaming while an assortment of uniformed military personnel watched from the side.

Years later, now released from the camp without charge and trying to rebuild his life in Serbia, Adayfi came across a photograph online of someone he says he recognised from that day. Until then, he says he knew the man as a young Navy lawyer stationed at the prison, but now he had a name: Ron DeSantis, the governor of Florida.

Adayfi says that the same man had watched the terrible episode unfold from behind a chain link fence.

“He was watching, and I was really screaming, crying,” Mr Adayfi, a Yemeni, tells The Independent in a lengthy video interview from his home in Belgrade. “I was bleeding and throwing up. We were in the block yard, so they were close to the fence.”

Mr DeSantis has spoken sparingly of his time at Guantanamo Bay, where he served between March 2006 and January 2007 with the US Navy, at 27-years-old, as a judge advocate general (JAG), a job which entailed providing legal representation to military personnel and ensuring the US military complied with the law. There is little mention of it in his new book and he has offered few details of what he did on the campaign trail.

But since serving at the controversial military prison, Mr DeSantis has consistently argued for it to remain open, and spoken against the release of prisoners, even though most are held for years without charge.

At a time when Mr DeSantis appears to be preparing to run for president, the accusations from the former prisoner may shed new light on the potential candidate’s military career. They allege that he witnessed treatment of detainees that the United Nations condemned as torture, and went on to become a champion of the facility that practised it.

In 2006, the year Mr DeSantis arrived at Guantanamo, the camp was roiled by hunger strikes, violent riots and protests from prisoners over their conditions. Camp officials began to take a more aggressive tack to bring the hunger strikes to an end in the early part of the year.

Mr Adayfi says his first interaction with the young navy lawyer was memorable. When they first met, he didn’t know his name – camp staff do not use their real names around prisoners for security reasons – but the man he would later come to learn was Mr DeSantis told Mr Adayfi that he was there to help him.

“I don’t remember exactly when DeSantis came because we had no watch, no calendar, nothing,” he says. “He came to talk to us along [with] others – medical staff and interpreters. And we explained to him why we were on hunger strike. And he told us, ‘I’m here to ensure that you get treated humanely and properly.’ We were talking about our problems with the brothers, the torture, the abuses, the no healthcare.”

“This was something strange, because nobody told us that before,” Mr Adayfi adds.

Mr DeSantis was memorable for his appearance, too.

“He was handsome with beautiful eyes,” he says.

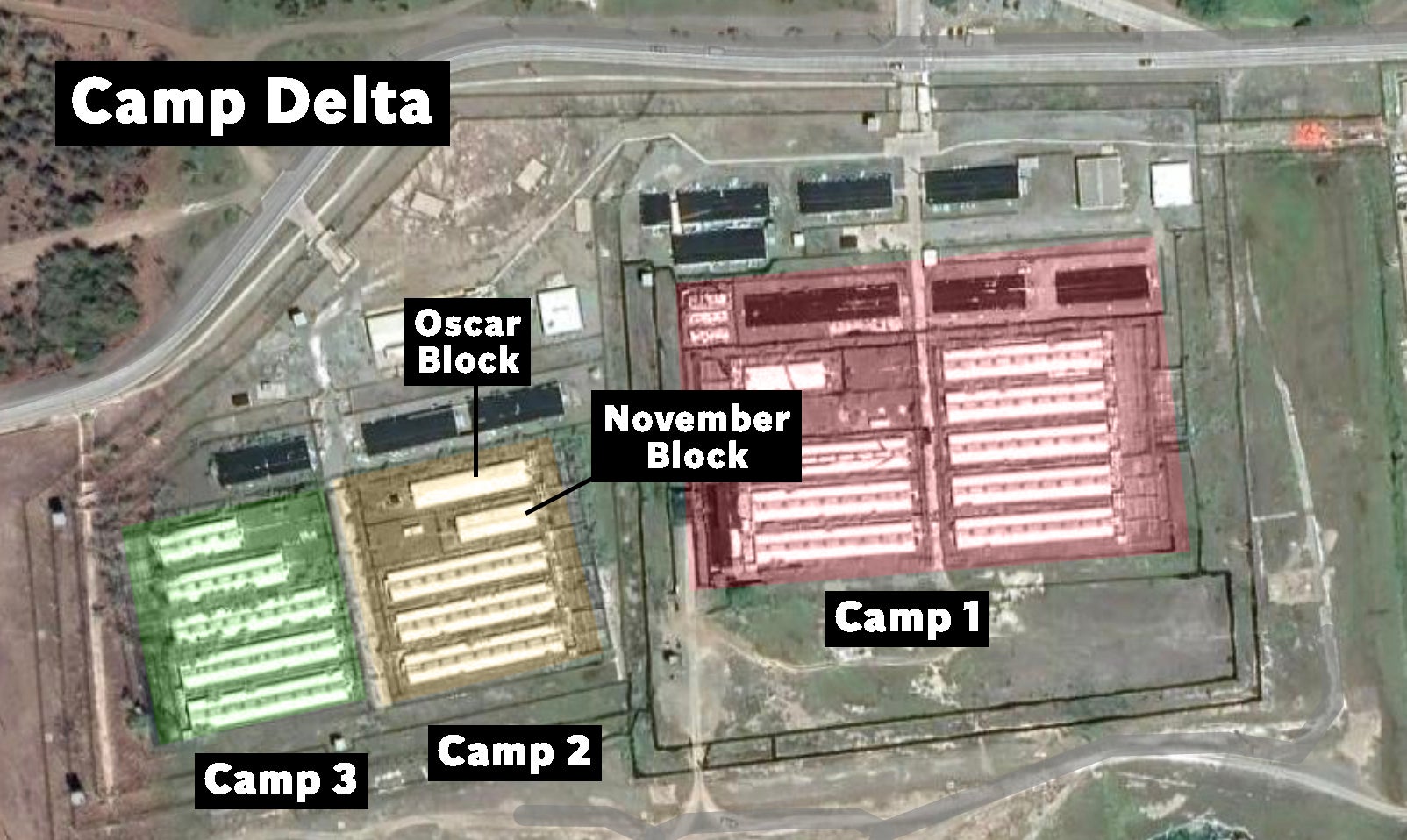

Mr Adayfi recalls that he initially believed Mr DeSantis when he told him he was there to help, but he says that quickly changed after he claims he was present for his force-feeding. On the day in question, Mr Adayfi says Mr DeSantis was standing behind a fence in the yard behind the November and Oscar blocks of Camp Delta, watching him being strapped to the chair and force-fed.

He knows about everything – about the hunger strike, the torture, the abuse in the camps. And his job was to ensure that we were treated humanely— Mansoor Adayfi

“He was there with medical staff, there was other officers, there was some interpreters. There was like a group of them there,” he says.

In his memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here, Lost and Found at Guantánamo, Mr Adayfi describes one incident of force-feeding in detail.

“Guards pushed me into the chair. They tightened the chest harness so that I couldn’t move, then strapped my wrists and legs to the chair. Every point of my body was tightly restrained – I couldn’t move at all. One of the male nurses stood in front of me holding a long, thick rubber tube with a metal tip. Another nurse grabbed my head and held it tightly while the male nurse forces that huge tube into my nose. No numbing spray. No lubricant. Raw rubber and metal sliced the inside of my nose and throat. Pain shot through my sinuses and I thought my head would explode. I screamed and tried to fight but I couldn’t move. My nose bled and bled, but the nurse wouldn’t stop.

“When they were done feeding me, the nurse pulled hard on the tube and ripped it out of my body. It felt like a knife coming through my nose and it bled badly. Blood ran everywhere. I couldn’t breathe and my stomach was so full I thought I would explode.”

Throughout lengthy questioning from The Independent about the finer details of his interactions, Mr Adayfi was insistent that the man he knew as a lawyer at Guantanamo was Mr DeSantis. Mr Adayfi’s description of his initial interaction with Mr DeSantis, for example, where he claims the young lawyer explained his role at the camp, matches the description given by Mr DeSantis’s superior of his job. The dates of key events in the camp during 2006 – such as the deaths of three prisoners – match publicly available information regarding the timeline of Mr DeSantis’s posting.

‘Amounting to torture’

Mr Adayfi characterises the forced-feeding episodes he suffered as torture. That assessment is supported by numerous United Nations reports, including one in 2006 which said of the practice at Guantanamo: “[t]he excessive violence used in many cases during transportation, in operations by the Initial Reaction Forces and force-feeding of detainees on hunger strike must be assessed as amounting to torture as defined in article 1 of the Convention against Torture.”

The World Medical Association said in 2006 that the force-feeding of hunger strikers “constitutes a form of inhuman and degrading treatment”.

The US government, over several administrations, has defended the practice and consistently denied that it amounts to torture. In a lawsuit brought by four detainees in 2013, government lawyers said of the practice: “It is the policy of the Department of Defense to support the preservation of life and health by appropriate clinical means and standard medical intervention, in a humane manner, and in accordance with all applicable standards.”

Barack Obama, who as a candidate promised to close the prison at Guantanamo, but defended force-feeding there when he was president, replied to a question about it by saying: “I don’t want these individuals to die.”

After Mr Adayfi says he saw Mr DeSantis at one of these force-feeding incidents, he didn’t talk to him again.

“At that time, I don’t want to see his face. But other prisoners, they talked to him. Some of the prisoners splashed him with faeces and urine and spit on him,” he says.

Mr Adayfi was released from the prison camp in 2016 with no charges. He kept in touch with other former detainees spread across the world in various locations and started to try to rebuild his life. Then one day, in 2020, he saw a photograph of Mr DeSantis online.

He says he shared the image with some other released former detainees, who also recognised him. He also shared the image with his book editor at the time, Antonio Aiello. When contacted by The Independent, Aiello confirmed this account and says he had multiple discussions with Mr Adayfi about Mr DeSantis going back roughly two years.

Mr Adayfi first made the claims publicly in November 2022, on the Eye’s Left podcast. That account of Mr DeSantis’s presence during force-feeding matches the one he gave to The Independent.

But Mr Adayfi is not the only former detainee who says that they recognised Mr DeSantis from their time at the prison camp.

Ahmed Abdel Aziz, a former prisoner who was released after 13 years without being charged with a crime and is currently back at home in Mauritania, also claims that Mr DeSantis witnessed the force-feeding at Guantanamo.

Although he did not take part in the hunger strike himself, Mr Aziz tells The Independent that he witnessed “dozens” of force-feeding sessions in 2006 himself, and it was not uncommon for large groups of camp staff to watch them from the side.

“Sometimes a big bunch of people will come, sometimes two or three, sometimes the medical staff would come alone with the guards. Among them was this man,” he says, referring to Mr DeSantis.

“He was not there all the time,” he says. “He was watching. He cannot stop it, he doesn’t have the authority, but he could stand against that or write to his higher-ups, to Washington, to other departments and tell them what’s going on.”

Like Mr Adayfi, Mr Aziz says doesn’t remember exactly when he realised the lawyer he knew from Guantanamo was Mr DeSantis, but he dates it roughly to a few years ago, when one of his friends sent him a picture.

”As soon as I saw his picture I know him very well because he spent a long time there, maybe six months or eight months,” he says. “Most of the people in there, once we see them, we don’t forget them,” he adds.

Mr Adayfi says he believes the American people should know that Mr DeSantis – now a national political figure on the cusp of declaring a run for the White House – was aware of and observed what he endured at Guantanamo.

“I’m not trying to say DeSantis was giving orders to the force-feeding. I didn’t see him giving orders to the guards, and I don’t think he was in a position to give orders to the guards. But he was there watching. He knows about everything – about the hunger strike, the torture, the abuse in the camps. And his job was to ensure that we were treated humanely,” he says.

Mr DeSantis’s military records show that he had duties at Guantanamo Bay Naval base between 1 March 2006 and 31 January 2007. His duties are listed as “Trial Counsel, Command Services Attorney,” as well as JTF-GTMO scheduler/administrative officer.”

Retired Navy captain Patrick McCarthy, who served as staff judge advocate at the detention facility and supervised Mr DeSantis, said in a 2018 interview that his duties required interacting with detainees and hearing their complaints.

“If any complaints were raised, Ron would have been among the folks I sent down to talk to the detainees,” Mr McCarthy told the Miami Herald. He said in the same interview that Mr DeSantis would have made sure the complaints “were addressed in a way that was consistent with the law”.

In his recently released book, The Courage to be Free, Mr DeSantis wrote that part of the reason he enlisted in the military in 2004 was so that he might be able to take part in prosecutions at the camp.

“One recruiter told me that the assumption was that the Iraq campaign would be over relatively quickly, and that there would be a need for military [judge advocate general’s] to lead prosecutions in military commissions of incarcerated terrorists at Guantánamo Bay,” he wrote. He added that it “seemed like a good opportunity to make an impact.”

At the time, allegations of torture and ill-treatment of detainees at the camp were rife. The International Committee of the Red Cross, which had conducted visits to the camp since 2002, wrote to the US government in June 2004 to decry the system of interrogation there as “an intentional system of cruel, unusual and degrading treatment and a form of torture”. The report, which became public in November of that year, alleged “humiliating acts, solitary confinement, temperature extremes, use of forced positions”, as well as exposure to persistent loud noise and music and “some beatings”.

The use of torture at Guantanamo Bay – euphemistically referred to as “enhanced interrogation” by the Bush administration – was approved by defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld for use as early as 2002. Those techniques included “hooding, stress positions, isolation, stripping, deprivation of light, removal of religious items, forced grooming, and use of dogs”, according to a 2005 Human Rights Watch report.

The chaotic situation at the camp continued throughout the year. On 10 June 2006, three prisoners died in one night. The US military determined that Yassar Talal al-Zahrani, Mani Shaman Turki Al Habardi al-Tabi, and Ali Abdullah Ahmed, all died by hanging, but researchers claimed the investigations into their deaths "failed to conform to minimum standards”.

Enemy combatants

As of February 2006, the month before Mr DeSantis arrived, the US government held more than 500 prisoners at Guantanamo Bay as alleged “enemy combatants”. Mr Adayfi was one of them.

Born in a small village in Yemen, he was just 18 when he went to Afghanistan in 2001 to conduct what he says was a research mission into al-Qaeda on behalf of a sheikh at an Islamic institute outside of Sanaa, the Yemeni capital. According to his account, detailed in his book, Mr Adayfi was captured by Afghan warlords and handed over to the CIA at a time the intelligence service was offering rewards. He then says he was taken to a CIA black site, where he was tortured.

According to a Department of Defense file on Mr Adayfi that called for his continued detention in Guantanamo, dated 2008, the US government described Mr Adayfi as “an admitted member of al-Qaeda who possessed prior knowledge of the 11 September 2001 attacks as well as other planned attacks against US interests”, and also claims that he was “identified as a commander of evacuating front line forces assessed to be Usama Bin Laden’s (UBL) 55th Arab Brigade during hostilities against US and Coalition forces”.

Mr Adayfi says he repeatedly denied the interrogator’s accusations that he was a member of al-Qaida, but says he later gave a false confession in anger at his ill-treatment.

“I was angry. I was hurt. I said things that I didn’t mean, but I was in a deep, dark hole,” he recalled in his memoir. “I wanted to teach them that they couldn’t kill and torture us and expect us to love them for it.”

Before his release, the US government also amended its assessment of Mr Adayfi, saying in a declassified report that it was “unclear whether he actually joined” al-Qaeda and was “probably … a low-level fighter”.

Mr Adayfi’s sister and brother died during the 14 years he was held at Guantanamo. He emerged from the prison he entered at 19 years old a different person. He says he still suffers from the impact of the time he spent at Guantanamo, and the force-feeding was just one part of it.

“They totally destroyed our life. The interrogations, sexual assault, the beatings, the long-term confinement, mental, psychological, physical abuse, just name it,” he said of his treatment at the prison camp and in CIA custody before his arrival.

“They broke our lives, and we still struggle to live now,” he adds.

When asked how he feels about Mr DeSantis today, Mr Adayfi says he has no ill will towards him, but does not believe he should be president.

“He’s a bad person, you know. I like America, and such people, when they come to power, they create a lot of problems.

“I have no hate against him. But at the same time, as a lawyer, as someone who is a graduate of law and believes in the law, he should have known better,” he says.

“I would ask him why would he want to keep Guantanamo open. As a lawyer, there should be a presumption of innocence, not guilt. If you love your country, if you love your people, if you believe in American values, you should be the first one who called for the closure of Guantanamo. And if you think we are criminal terrorists, okay, take us and try us before your justice system.”

Following his time at Guantanamo, Mr DeSantis went on to serve as a JAG in Iraq. Later, he became a congressman for Florida’s sixth congressional district, at which time then-president Barack Obama had proposed closing the prison by executive order. Mr DeSantis spoke out numerous times against the idea.

At a congressional hearing chaired by Mr DeSantis in 2016, the then-congressman forcefully argued for Guantanamo to remain open.

“The president’s conclusion that the detention facility should be closed is based in part on his idea that the facility is a recruiting tool for Islamic jihadists, but this represents a misunderstanding of the nature of the terrorist threats we face.,” he said. “These are not the type of people that will abandon their jihad against America and our allies simply because we close Guantanamo Bay,” he told the House of Representatives Subcommittee of National Security, part of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

In the same session, he spoke briefly of his time there.

“When I was in the Navy I was there for a time and it is a very professionally run facility. Anybody in this room would rather spend a night there than in like the Fallujah jail or something like this. I mean, it is just night and day. And the people that are guarding that facility are under an awful lot of pressure because those detainees are very hostile to them, and they know that if they do anything that they are all of a sudden going to be subject to – so it is a very stressful environment for our uniformed personnel who are there,” he said.

In a campaign ad for his successful 2018 run for governor, images of Mr DeSantis in his navy uniform are shown as a narrator described him as a “JAG officer who dealt with terrorists at Guantanamo Bay.”

Mr DeSantis’s office did not respond to several requests for comment.