It is impossible to miss the political symbolism in Meenambal Sivaraj (M.S.) Nagar in the heart of Chennai. At the entrance to the Ambedkar Ground located in one corner of the locality stands an arch, constructed to mark the birth centenary of the leader who gave India its Constitution.

The spot near this ground has busts and statues of Ambedkar, Pandit Iyothee Thass, Rettamalai Srinivasan, ‘Periyar’ E.V. Ramasamy, and A. Sakthidasan (of the Republican Party of India) -- leaders who fought against caste. The area’s name (after leaders N. Sivaraj and Meenambal Sivaraj) and the statues near the ground are an indication of how M.S. Nagar, with a predominantly Dalit population, was once a politically-thriving locality. Ironically, it has been struggling for decades to secure the land rights of its own people.

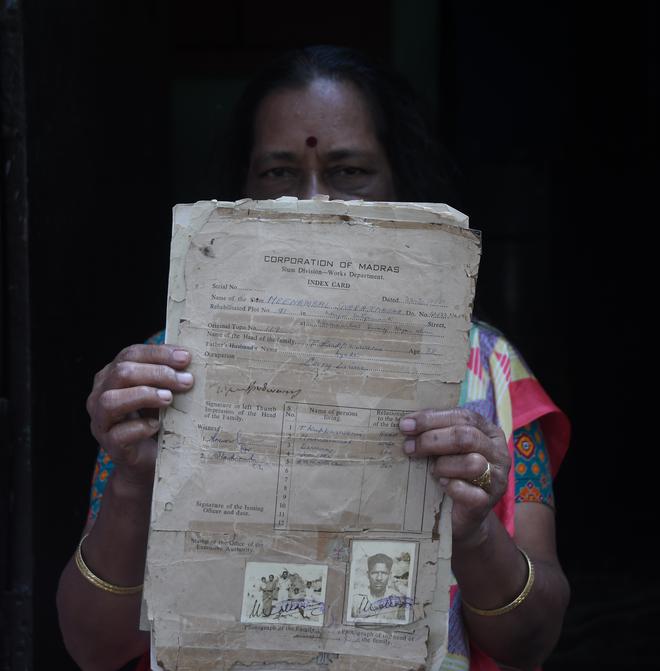

A few metres away from the ground, 40-year-old Jyoti*, in her house, opens a bag full of yellowing documents, some of which are nearly 70 years old, to show her family’s rootedness in the locality and their continuing struggle to secure ownership for the plot they live on. The documents were safeguarded by her late grandmother in an old trunk that survived many a fire in the locality that was once filled with huts.

One of the oldest documents in Jyoti’s possession is a 1959 certificate provided by the then Corporation of Madras. The photograph in the document shows her grandmother and grandfather, in front of their hut with their three children. “This was the first document recognising that they were residents of this plot. But my grandmother had told me that they had moved here many years before that,” said Jyoti.

After living on the plot for at least 70 years and despite promises made by the government, land rights still elude Jyoti’s family. This is not the story of only Jyoti or the nearly 150 more families in M.S. Nagar, but that of at least 57,000 more families across hundreds of settlements in Chennai and 28,000 more in nine other cities in Tamil Nadu as per conservative estimates of the State government.

The promise

While there had been other smaller schemes for providing land to the urban poor, these families were promised land ownership predominantly under three different projects launched by the State government between 1977 and 1988. They were the Madras Urban Development Project (MUDP) I (1977), MUDP II (1980), and the Tamil Nadu Urban Development Project (TNUDP) I (1988), all of which were funded to a large extent by the World Bank, through loans.

These projects marked a departure in the focus of the Tamil Nadu Urban Habitat Development Board (formerly Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board), which had until then, focused, to a large extent, on clearing slums and resettling them in multi-storey apartments. In contrast, these projects had a component called “slum improvement,” through which infrastructure was improved by providing basic amenities in areas where the poor had settled, despite not owning the land. The plots were sold to them on a hire-purchase basis with the cost recovery planned through monthly repayments for a fixed number of years.

M.S. Nagar was among the first of 53 localities taken up in Chennai during MUDP 1, covering around 25,000 families. MUDP II covered around 60,000 families in Chennai and TNUDP I covered around 77,000 families in Chennai and nine other cities in Tamil Nadu, including Coimbatore, Madurai and Tiruchi.

R. Geetha, advisor, Unorganised Workers Federation, said, as a young activist, she was among the many who opposed the scheme at that time since the people were asked to pay for the infrastructure and land. “We were of the view that the land had to be provided free of cost. In hindsight, the scheme was a good one, as it ensured land rights for the poor, which is very important,” she said, adding that it was unacceptable that these rights have not been realised even after four decades.

An arduous struggle

In the case of Jyoti, all the fragile papers in her possession, including bills proving the monthly repayments, have not helped obtain a sale deed since she was not able to produce the original allotment order given to her late grandfather. “The Board should also have a copy of this allotment order. However, they are not willing to check for it, despite the other substantiating documents that we possess,” she said.

Illustrating how the problems compound as years pass by, Jyoti says that with the original allottees dead and the families expanded with each generation, many families were facing internal struggles on the issue of who among the second generation should get the sale deed.

“In some cases, original allottees have moved out for livelihood reasons, selling their allotment orders to other families without the approval of TNUHDB. The board, however, says they can issue sale deeds only to the original allottees,” she said.

In many localities The Hindu visited, people seemed to have little awareness of their right to land ownership or the procedure to obtain it. Many others who are aware have tried in vain. M. Azhagu Maistry, aged around 70, of Periyar Street in M.G.R. Colony, said he had all the original documents and receipts. “When we were given the allotments, I remember people saying that we would eventually get pattas. However, there is no one to guide us,” he said.

On the other hand, T. Kumaran, a resident of Avvaipuram, followed up persistently with the board and paid ₹35,000 demanded as dues and interest for the years passed. “Despite this, they have neither provided me with the sale deed nor a document acknowledging that all my dues have been settled,” he said.

N. Thiruvengadam (69), a resident of Jakir Hussain Street in M.G.R. Nagar, who has also settled all his dues, filed a case in the Madras High Court, which directed TNUHDB and other departments concerned in 2015 to consider his petition for issuance of sale deed. “It has been eight years, I am still waiting. I want to initiate contempt proceedings in the court, but my neighbours are less hopeful,” he said.

Mani,* a resident of Moovendar Nagar (called Naduvankarai Pillaiyar Colony in official records of the board), alleged that lower rung officials of the TNUHDB demanded bribes to process his documents, a complaint heard in few other localities as well. “I lost hope and stopped trying 10 years ago,” he said.

Seventy-year-old K. Vasuki, a resident of M.S. Nagar, was among the few who relentlessly pursued her case with the board for more than a year and successfully obtained a sale deed. “The amount I had to pay was revised multiple times without clear reasons. I paid all of that and got the sale deed,” she said.

However, she was in for a surprise when she went to the taluk office to obtain a patta. The revenue officials said the land, subdivided into plots, was not updated in their systems. And this indicates perhaps the most complex problem to be solved in the issue: who owns these lands?

Who owns the land?

In the case of M.S. Nagar, officials said the land has been transferred to TNUHDB, but a survey may be required to update revenue records with subdivided plots. In some other cases, the land where families had been settled belonged to other departments like Revenue, Public Works, Water Resources or in some cases even temples managed by the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (HR&CE) Department.

The alienation of these lands by the other departments to TNUHDB should have happened during the commencement of these World Bank-funded projects. However, World Bank documents and government orders issued at that time, showed that TNUHDB was provided “enter upon” permission to develop infrastructure in these lands due to time constraints, with the understanding that the land alienation could be done later. Although several years have passed, the land alienation is yet to be done in many areas.

Threats of eviction

In some places where land alienation has not been done, people who were once promised ownership of the land now face threats of eviction, especially in localities that were located close to water bodies. In a few places, evictions have already taken place.

Muthuselvi,* who held an allotment order for a plot in Moovendar Nagar under MUDP, was evicted a few months ago. TNUHDB’s order, unilaterally cancelling the allotment order, said that the area was located close to the Cooum River and the Public Works Department needed the land for “river expansion”.

A senior official, who formerly served on the board, said that people who were covered under MUDP or TNUDP but faced eviction should have ideally been provided with compensation for the land not just on principles of natural justice, but also because many had paid for the land. “Had things worked as intended, they would have been title holders of the land,” he said.

Mr. Kumaran said 74 households were allotted plots in Avvaipuram on the banks of Cooum as part of MUDP by erecting a boundary wall along the river. He expressed concerns about rumours that these households may be evicted because of the Chennai Port–Maduravoyal Expressway project.

A Madras High Court judgement of 2012, delivered by Justice S. Manikumar, is considered one of the progressive judgements on the issue. In the case filed by S. Arokiam, demanding a sale deed for the plot allotted to him in Ullagaram under MUDP II, the Judge ruled in favour of not just the petitioner but the thousands of families awaiting sale deeds.

Stressing that these families cannot be seen as encroachers, the Judge said it was the TNUHDB that identified these areas, carried out development work and issued allotment orders. Citing a submission of TNUHDB, the judgement said even the areas located close to waterbodies cannot be treated as “poramboke” or “water resource” if they had lost the nature of being a water source.

Arguing that further delays in resolving this long-pending issue would lead to more complications and with consideration to the number of families affected across the State, Vanessa Peter, founder, IRCDUC, a community-centric hub for deprived urban communities, who had filed representations to TNUHDB on this, said that the government should consider forming a high-level committee to resolve this issue on a mission mode. She stressed the need for absolute transparency, clarity on procedure and outreach by TNUHDB to facilitate more people to apply for sale deeds.

A senior official from the board said that transferring land rights to families covered by projects like MUDP and TNUDP was a priority. He said the board was planning to simplify the procedures with the help of online systems. On allegations of bribery, he said stringent action would be taken on any such complaints. He expressed hope that increased transparency and simplification of procedures would help prevent such complaints. Another official pointed out that an empowered committee constituted by the government was looking into issues related to land alienation.

*Names changed to protect privacy