The cofounder of Store716 stood inside a Buffalo sports paradise. It was Sunday morning, and he was strolling past T-shirts printed with slogans that spoke to the magnitude of the afternoon ahead. Favorites include:

AVENGE THE 90s

BUFFALO VS. EVERYBODY

JOSH F*CKING ALLEN

WIN THE WHOLE DAMN THING

David Gram, the store’s co-founder, was born here, grew up here, went to college here and stayed here. He never considered leaving. Instead, while working at an advertising agency, he started a sports-gear side hustle with a colleague and fellow diehard. They sold hats and hoodies and key chains, but never at high volumes. “And then,” Gram says, “Josh Allen came along.”

The Bills quarterback changed their paradigm, allowing the marketers to open the brick-and-mortar store where Gram now stands. They like to describe their merch as “original Buffalo fan gear,” and this, from two advertisers, became an exercise in storytelling. They sold the collective experience of local sports fans, those devoted, rabid, tortured types who long ago decided the best way to prepare for games was to jump through tables after shotgunning beers. “We just have this feral desire for a championship,” Gram says. “It’s who we are.”

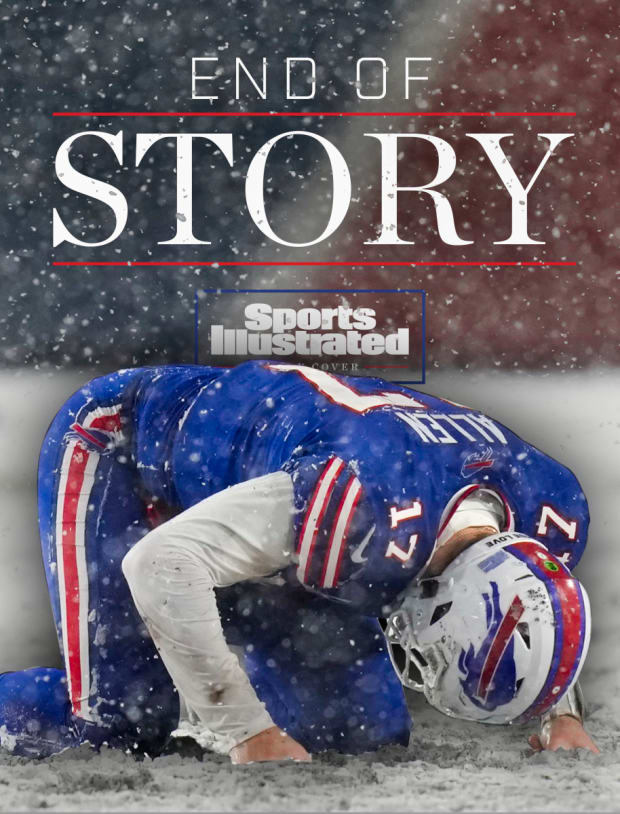

Seth Wenig/AP

On the wall behind him, near the cash register, there is a whiteboard. It announces “big news” related to a GoFundMe for Damar Hamlin, a donation of $41,716 to the Chasing M’s Foundation that Hamlin created long before that night. That donation marked the largest of nearly 250,000 contributions that funneled nearly $9 million to Hamlin’s efforts. All said something—about Bills Mafia, about Buffalo, about a community that supports and embraces and does right by its own.

Gram was watching at home that night, with his fiancé, a nurse. They witnessed Hamlin make a first-quarter tackle on Tee Higgins. They saw him get up and collapse. Gram’s fiancé believed Hamlin had gone into cardiac arrest. They watched, same as millions across the world, as paramedics and trainers resuscitated him, saving his life. The game was canceled. The season moved forward, unsteadily, especially in Buffalo.

Life must. Even in this place, where four straight AFC championship teams lost in four straight Super Bowls, where a racist mass shooter at an area grocery store killed 10 people in May and where a blizzard unlike any storm in this snow globe of a city claimed 47 more lives last month. No, football wasn’t life and death. But here, sometimes, it felt that way.

Gram wasn’t sure he wanted to sell anything related to Hamlin. The man’s heart had stopped, twice, on a football field. He decided to wait for positive news. There wasn’t much initially, when an ambulance rushed Hamlin to the hospital, while teammates wept and prayed and held each other tight. He was listed in critical condition, sedated and on a ventilator. But there would soon be better news.

Hamlin’s condition was upgraded. His father spoke to the Bills that Thursday, Jan. 4, demanding they play to honor his son. Two days later, Damar had his breathing tube removed. He also took his first steps since that night, with assistance. He began to text his teammates; he even, unnecessarily, apologized. By Monday the next week, he was back in Buffalo, at another hospital, for more tests. Doctors said he had already made “great progress.” Two days later, he was released. Soon, he went to visit his teammates.

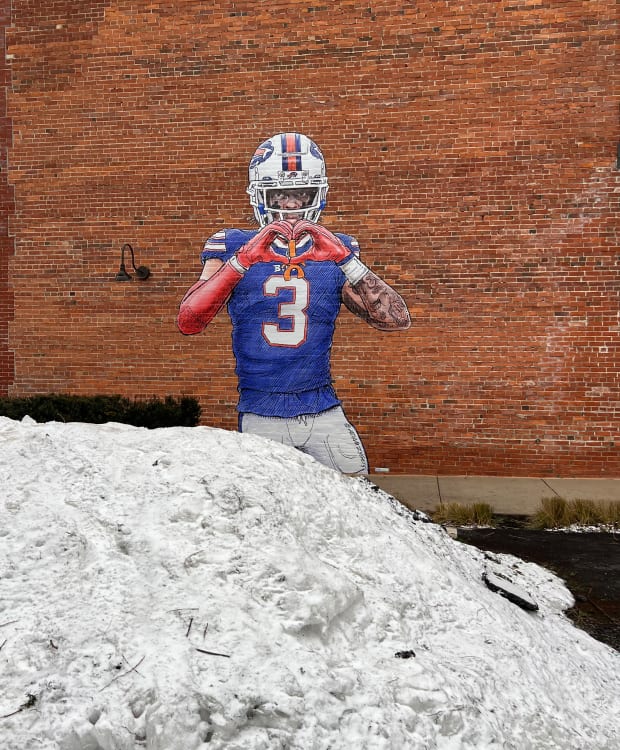

Store716 began selling Hamlin gear around then. Like the blue sweatshirts with the hearts underneath WE ARE DAMAR. Local sports fans threw their arms around him. Gram sold so many Hamlin T-shirts and sweatshirts that one of his employees came down with tendonitis in her thumb from preparing all the shipments.

Greg Bishop/Sports Illustrated

So, yes, on this Sunday morning, he considers Hamlin, along with the blizzard, the shooting and the history that now, to some, seemed to matter more than ever. Everything had become tethered—place and team tied even tighter. “We’re a city of so many heartstring stories,” Gram says. And a fan base that gets “kicked in the balls over and over again” but “always just rises up and does something. We keep going.”

He wondered two things, same as every other Bills Mafia member: Would Hamlin be at the game that afternoon against the Bengals? And: Would the Bills lift a city and region that had endured so much, at the most opportune time? Gram thought so. He knew so.

He shrugs. “This is Buffalo,” he says. “It was never going to be easy.”

All morning, anticipation heightened. Injuries, matchups, Allen, stars aligning and Labatt Blue combined for an optimistic vibe. Plus, Hamlin. Always, Hamlin. On Sunday morning, six hours before kickoff, fan after fan stopped by a mural painted on the side of an apartment building. There he was, No. 3, clad in a blue jersey and white pants. With both hands, he formed the shape of a heart, his signature in recovery. A police officer walked her dog over to take a picture, followed by a man in a neon windbreaker, followed by a family of four wearing Allen jerseys. No one said anything, but they nodded at each other. They, too, understood.

Greg Bishop/Sports Illustrated

Oddsmakers had made the Bills 5.5-point favorites, which didn’t sit well with the Bengals, who were underdogs only two other times this season. Players like running back Joe Mixon went out of their way to remind reporters that Cincinnati, a team that nearly won the last Super Bowl, remained the conference’s “top dog.” Mixon and teammates also took issue with the NFL’s decision to begin selling neutral-site AFC championship game tickets this week (because of the cancellation of that night’s game, the NFL determined a Chiefs-Bills tilt would be played in Atlanta). “Disrespectful,” Mixon said. After all, Buffalo still had to go through the conference’s defending champs.

There were hearts and No. 3’s and combinations of both all over downtown, near the casino and the hockey arena and the factories looming in the distance. It was as if the locals planned to will Buffalo forward, everyone connected by a brutal seven-month stretch that made them all more resilient, too.

They understood that the Bengals played 15 games this season without losing a single starting offensive lineman. But that had changed in recent weeks. Cincinnati had bolstered its protection of Burrow this offseason, signing right tackle La’el Collins, right guard Alex Cappa and center Ted Karras, then drafting guard Cordell Volson in the fourth round. But Collins went down with a left ACL and MCL tear against the Patriots in Week 16, Cappa went out with a left ankle injury against the Ravens in Week 18 and left tackle Jonah Williams sustained a dislocated kneecap in the wild-card playoff win over Baltimore. All three would be out against the Bills, and at Highmark Stadium, no less, where it’s cold and airplane-hangar loud. “Us against the world,” Burrow said.

Three hours before kickoff, the parking lots near Highmark were filled to capacity. Fans in snowshoes rolled coolers down the streets. Allen jerseys were everywhere—on a dog walker, on a dude manning a smoker, on parking-lot attendants, for sale in so many tents. But Hamlin gear was just as ubiquitous. The star and the inspiration, that was the sell; they accounted for the vibe. Plus, in the playoffs, Buffalo had been 13–1 at home since 1970. The Bills ranked second in scoring defense (17.9 points allowed per game) and second in scoring offense (28.4 points scored per game).

Greg Bishop/Sports Illustrated

The guys playing cornhole in those classic-style Zubaz pants predicated a blowout. As did the crew downing smash burgers at the tailgate lot near the corner of Abbott and Southwestern. Fires blazed. Fans carried WE BILL-IEVE signs. One sang a drunken rendition of God Bless America to an audience of zero—just the fan, her car and her microphone.

Sure, the quarterback had struggled at times this season, especially relative to 2021. He had turned the ball over too often. But the Bills were 14–3. They had won eight straight. They were balanced, explosive, and—considering the Bengals’ banged-up offensive line and Patrick Mahomes’s ankle sprain Saturday—as healthy as either of the other two teams still standing in the AFC.

The tents that lined Abbott Road peddled face-painting services, energy drinks, recovery drinks, pizza and chili dogs. The revelers ate and imbibed. Most believed that all signs pointed toward the same place: a necessary triumph, on to Atlanta, one step closer to Super Bowl LVII.

Shortly before kickoff, on the other side of the continent, Jordan Palmer had just finished a pancake breakfast with his two boys; they were heading home to help out with their baby sister.

As a private quarterbacks coach and a retired QB himself, Palmer mentors all manner of NFL signal-callers. Two that he has worked extensively with are playing that afternoon. Allen and Burrow can seem antithetical to each other—fans experience how Allen plays football, while Burrow operates with an unnatural calm. But Palmer sees a commonality, calling both “two of the most likable leaders in the league,” dynamic and clutch MVP candidates who take different routes to the same place. In this case, Highmark Stadium on Sunday afternoon.

Palmer doesn’t buy the sentiment that Allen has “regressed” this season. He’s 26 years old, after all, meaning that, for all his massive progress, he’s not anywhere near the finished product he will become. Before this season, he was also 3–3 in the playoffs, with 14 touchdown passes against only one interception. That changed in the wild-card round against Miami, when he took seven sacks, fumbled three times, threw two picks and still made the kinds of throws that drop jaws across the country. He still won. “Josh wasn’t good five years ago, six years ago,” Palmer says. “Joe wasn’t starting [at Ohio State] six years ago. They got better at a s---load of stuff really fast. They’re just not normal people.”

The game, Palmer says, will come down to factors that sound boring but remain critical: scoring touchdowns in the red zone, avoiding turnovers, kicking field goals. “It would have been the same answer when Jim Kelly was playing against Boomer Esiason,” he says. “Nothing changes.”

Palmer spoke to Allen in the aftermath of Hamlin’s collapse in Cincinnati. He spoke to shaken players all over the league. He hoped that moment lent them perspective, the kind that can be gleaned from only tragedy. But he also didn’t buy the notion that the inspiration of Hamlin’s recovery, large as it had grown, would lift Buffalo to certain victory. Palmer played for the Bengals in 2009, when wideout Chris Henry died after falling out of the back of a pickup truck. Teammates said the same things and made the same tributes. But when the Bengals needed to beat the Chargers to secure the conference’s top seed, “we melted in the fourth quarter,” Palmer says.

He adds, “I could see it go both ways.”

He was not wrong. Light snow began to fall an hour before kickoff, as fans streamed inside. One wasn’t wearing a shirt. Another was … Peyton Manning. Snow. Quarterbacks. History. Drama. And: Hamlin was in the stadium, making his first public appearance since the last time these teams played.

For Bills Mafia, the game started so poorly that “disastrous” fails to fully capture it. The Bills won the coin toss and deferred. That gave Cincinnati the ball, and the Bengals held it for most of the first half.

The Bengals scored touchdowns on their first two possessions. The Bills went three-and-out the first two times they had the ball. As he is most Sundays, Joe Burrow was the best player on the field. He threw for 186 yards and two touchdowns in the first half alone.

Then the Bills started to build toward a moment. Josh Allen found his favorite target, Stefon Diggs, for a completion, a positive sign on an afternoon absent positive signs. Allen nearly scored on a QB sneak near the goal line, while dragging what seemed like half of the Bengals’ defensive line with him. He plunged in on the next play, and it was 14–7.

In response, the Bengals mounted a drive. That’s when the moment came. At the two-minute warning, the big screens at Highmark Stadium flashed to a suite. With the snow and the glare from the lights, it was difficult to see anything. Then, suddenly, the picture became clearer. There was Hamlin, holding up both hands, through which he formed a heart. It’s the only thing that could make all of Buffalo turn away from the field. They fashioned their hands into hearts, too, while screaming and saluting and jumping up and down.

But even after the Bills defense held Burrow and company to a field goal, it wouldn’t change anything. The Bengals converted 60% of their third downs, picked up 30 first downs and punted just twice all afternoon. The game never got closer than the seven-point lead Cincinnati had taken with that opening-drive touchdown—at no point in the second half did the Bills have a possession with a chance to pull even. On Sunday evening, Burrow twice took snaps in victory formation from just outside the Bengals’ end zone, and Buffalo’s season was over.

Afterward, Bills coach Sean McDermott dismissed many of the obvious what-went-wrong questions. He didn’t think his players lacked energy, as some had said; the Bengals’ holding the ball that long in the first quarter had taken the Bills out of their offensive rhythm. He didn’t have an issue with Diggs’s early exit from the postgame locker room or sideline histrionics, because he believed both were borne of frustration, the kind that makes him an elite competitor. He didn’t believe that Buffalo’s window for Super Bowl contention is closing or had closed. He was proud of this group, because their season had turned into more than a normal playoff season. It had become about survival, about circumstances without precedent. “We just didn’t do enough to win,” he said. “No excuses. They beat us.”

Sam Greene/The Enquirer/USA TODAY NETWORK

His players mostly echoed their coach’s sentiments. The Bengals were simply good. They might win the title that slipped through their grasp last February. They had won playoff games in consecutive seasons for the first time in team history. But some Bills still admitted to just how heavy the emotions have been the past few weeks. “We want to win,” left tackle Dion Dawkins says. “We try to compete at a high level all of the time. And sometimes it gets us. That’s the sucky part of being human.”

Some members of Bills Mafia, having been kicked in the balls again, might have taken issue with that most human of answers. Most surely understood that this season had not been like other seasons. Hamlin’s health was more important. The community that embraced them was more important. The blizzard, the shooting, real life, all of that was more important. An optimistic Buffalo sports fan—you know who you are!—might look at everything the team endured and consider how much that will inform the story of next season. Or, how it will feel when, sometime in the near or perhaps distant future, the Bills finally, mercifully, hold the Lombardi Trophy as high as they can after they’ve won the whole damn thing.