The white paper beneath her crinkles as she shifts to look at the medical objects in the room. She’s had the coronavirus three times. no one can figure out why.

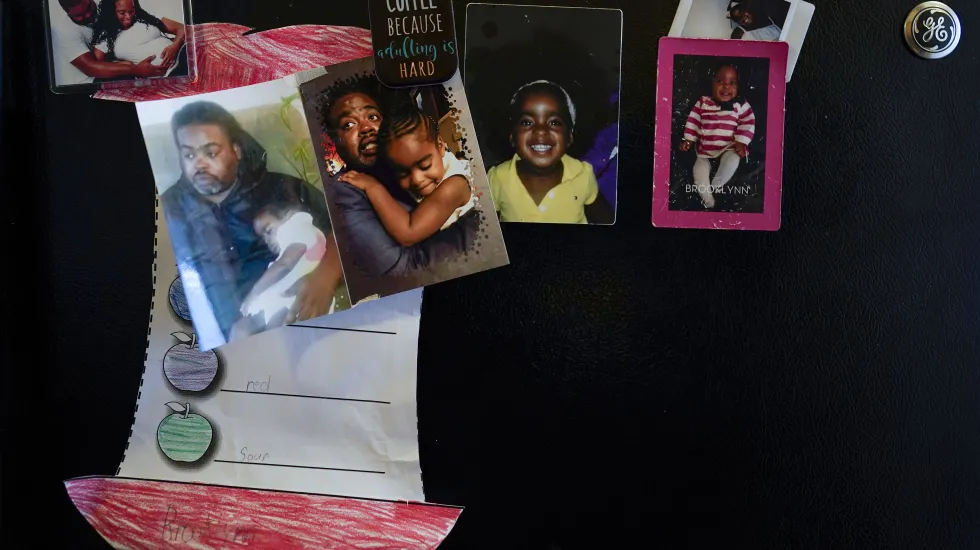

In a way, though, Brooklynn’s lucky. Each time she has tested positive, she has suffered no obvious symptoms.

But her father Rodney caught the virus — possibly from her — in September and died from it.

Her mother Danielle is dreading a next bout, fearing her daughter could become gravely ill even though she’s been vaccinated.

“Every time, I think: Am I going to go through this with her, too?” she says. “Is this the moment where I lose everyone?”

Among the puzzling outcomes of the coronavirus, which has killed more than six million people worldwide since it emerged in 2019, are the symptoms suffered by children. More than 12.7 million children in the United States alone have tested positive for COVID since the start of the pandemic, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Generally, the virus doesn’t hit kids as severely as adults. But, as with some adults, there are still bizarre outcomes. Some suffer unexplained symptoms long after the virus is gone — what’s often called long COVID. Others get reinfected. Some kids seem to recover fine, only to be struck later by a mysterious condition that causes severe organ inflammation.

And all of that can come on top of grieving for loved ones killed by the virus and other interruptions to a normal childhood.

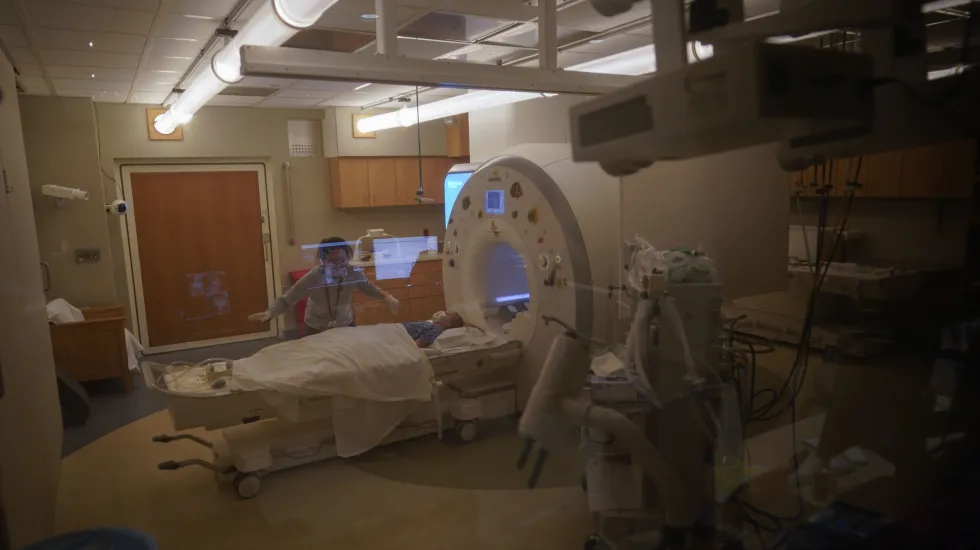

Doctors at Children’s National and other hospitals getting money from the National Institutes of Health are studying the longterm effects of COVID on children.

The goal is to be better able to evaluate the impact on children’s health and development physically and mentally — and learn more about how their developing immune systems respond to the virus to learn why some fare well while others don’t.

Children’s has about 200 kids up to age 21 enrolled in the study for three years. It takes on about two new patients each week.

The study involves kids who have tested positive and those who haven’t, such as siblings of sick kids. The subjects range from having no symptoms to requiring life support in intensive care. On their first visit, participants get a full day of testing, including an ultrasound of their heart, blood work and lung function testing.

Dr. Roberta DeBiasi, who runs the study, says its main purpose is to define the many complications children might get after contracting the virus and how common those are.

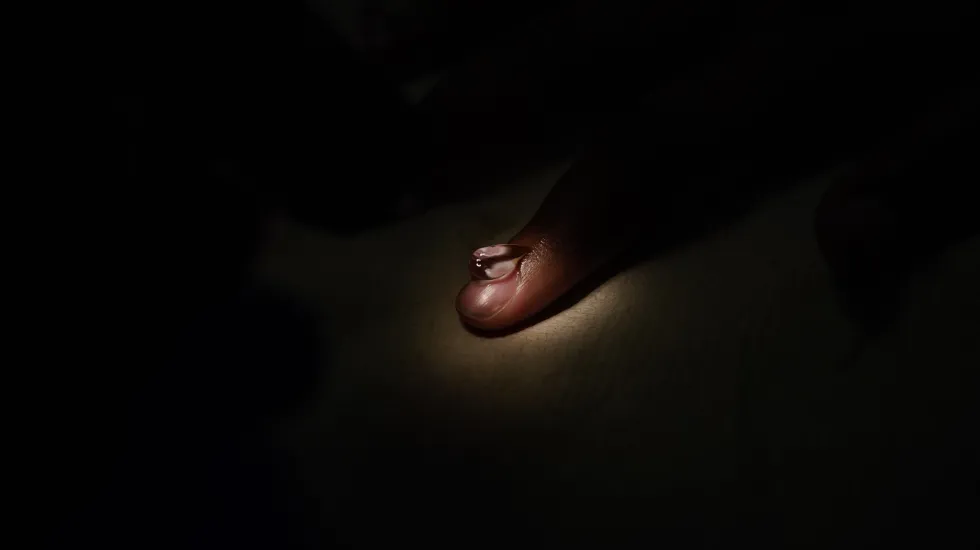

Alyssa Carpenter is another child enrolled in the study. She has had COVID twice and gets fevers that break out unexpectedly and other unusual symptoms. Alyssa was just 2 when she started in the study and has since turned 3. Her feet sometimes turn bright red and sting with pain. Or she’ll lie down and point her little fingers to her chest and say, “It hurts.”

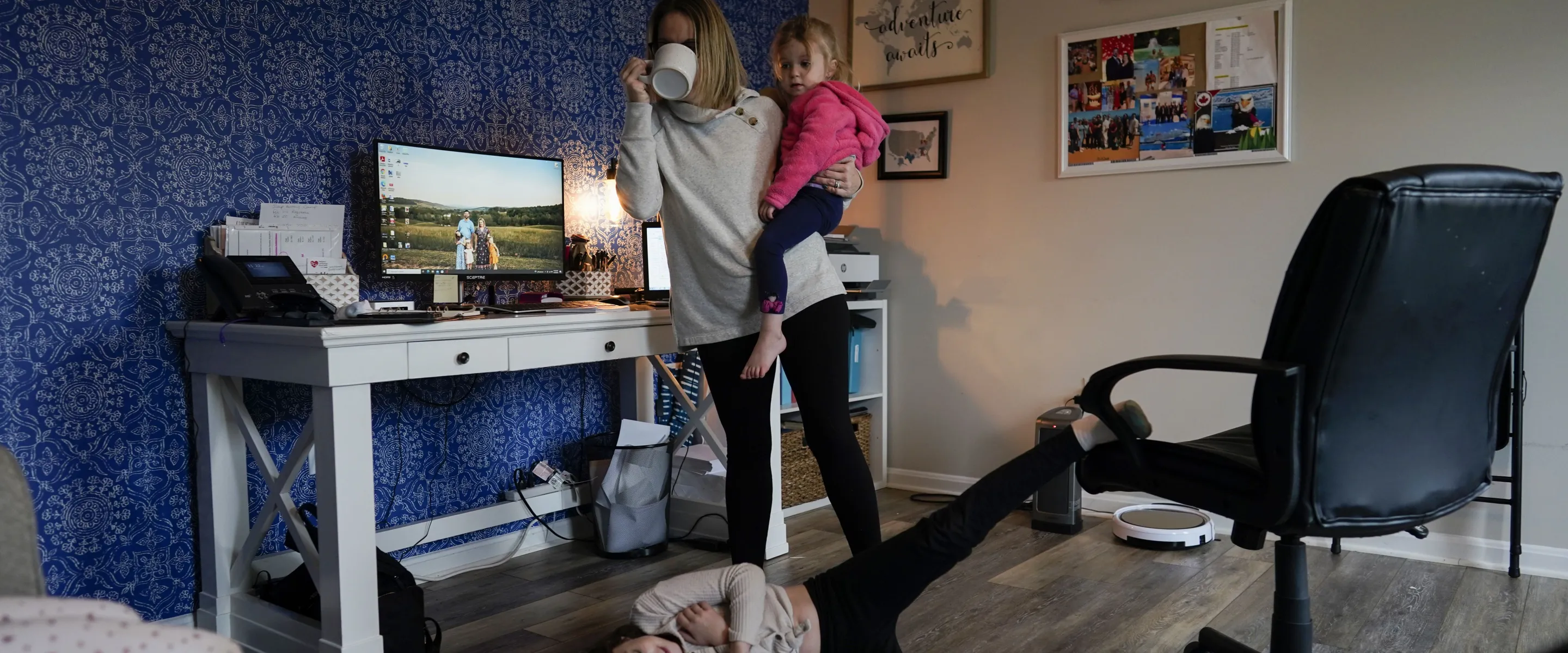

Her parents Tara and Tyson Carpenter also have two other daughters: 5-year-old Audrey and 9-year-old Hailey, who is on the autism spectrum. As it has been for many parents, the pandemic has been a nightmare of missed school, unproductive work, restrictions and confusion.

Beyond the anxiety many parents feel, they have another concern for their toddler. They just don’t know how to help her.

“It was just super-frustrating,” Tara Carpenter says. “We’re trying to find out answers for our kid, and nobody could give us any. And it just was really frustrating.”

Alyssa would wail in pain from her red burning feet or whimper. She’d come down with a fever but suffer no other symptoms and be sent home from school for days, ruining Carpenter’s work week.

But then in ballet class, with her pink tights and tutu, she’d seem totally fine.

In the past few months, her symptoms have begun to subside. That’s giving the family some relief.

Still, Tara Carpenter says: “After the fact, what do we do about this?” We don’t know. We literally don’t know.”

For some families in the study, a child suffering from long COVID is the easy one during the hospital visits. On a recent day, another family finds that it’s the older sister Charlie who dissolves into tears because she doesn’t want blood drawn while younger sister Lexie, by now used to being prodded by nurses and doctors, hops up on the table.

The family dynamics can be tough: The child with the illness might get more attention, which can create problems for other siblings. Exhausted parents struggle with how to help them all.

The children are given full medical check-ins. They also receive a full psychological assessment, run by Dr. Linda Herbert.

Herbert asks the kids about fatigue, sleep, pain, anxiety, depression and peer relationships. Do they have memory concerns? Are they having a hard time keeping things in their brains?

“There’s this constellation of symptoms,” she says. “Some kids are incredibly anxious about getting COVID again.”

Psychological symptoms are among the most common, and it’s not just the kids with COVID. It’s their siblings and parents, too.

Brooklynn’s mom Danielle Mitchell feels the stress. She’s a single mother working full time, grieving the loss of her partner and trying not to seem too depressed in front of her daughter. She was motivated to enroll Brooklynn in the study by wanting to draw attention to the need for vaccines, particularly in the Black community.

“My baby keeps getting it,” she says. “Can’t the people around us try to protect her?”

Brooklynn whimpers when she hears she has to get blood drawn and asks, “Do you have to?”

“Yes, baby,” the nurse says. “It’s so we can figure all this out.”

“If her daddy was here, he’d take her to Dave & Busters after this,” Mitchell says.

Then, she lowers her voice so her daughter can’t hear what she says next — that her longtime partner Rodney Chiles wasn’t vaccinated.

She says he had qualms, as many do, about the vaccine and was waiting to get it. Shortly after Brooklynn tested positive during the run of the Delta variant, he started feeling sick and went downhill fast. Chiles had other medical conditions, too, which accelerated his death. He was 42.

“He called us on a Sunday,” Mitchell says. “He was, like, ‘They are about to intubate me because I can’t keep my oxygen up. And I love y’all, and, Brooklynn, forgive me.’ It was the last time he talked to them before he died.

“I’ll tell you what,” Mitchell says. “The only reason I’m still here is because I have a child.”

On school days, Mitchell picks up Brooklynn from Rocketship Rise Academy Public Charter School. Hand in hand, they walk to the car for a short ride before she resumes work, from her home office in her bedroom, with a not-for-profit organization.

One recent day after school, as Mitchell had a Zoom meeting, Brooklynn munched popcorn and talked about how she and her dad bought a pair of tennis shoes and balloons for her mom last year on Mother’s Day. They forgot her mom’s shoe size and had to come back home and check the size. She giggles as she tells it.

In her room, there’s a big photo of her with her dad, though she usually sleeps in bed with her mom now.

“Even though kids aren’t as sick, they are losing,” Mitchell says. “They’re losing parents, social lives, entire years. Yes, kids are resilient. But they can’t go on like this. No one is this resilient.”