Readers are advised this piece contains some racist terminology.

Today, the Australian public mostly sees a conservative Australian Jewish communal leadership that has, since the 1990s, rarely spoken out on anything unrelated to Israel or the Holocaust.

Both issues are often drawn together. Arguments for Israel’s defence are often bolstered by the memory of the Holocaust. That the Holocaust is an inevitable cause of conservatism and Zionism has become part of a commonsense idea of, and about, Australian Jews.

But as I argue in my book, Jewish Antifascism and the False Promise of Settler Colonialism, the seemingly natural connection made between Israel and Holocaust memory has shifted over time.

In fact, Australian Jewish communities have long fought internally over the best strategy to achieve Jewish safety.

The memorialisation of the Holocaust was key to the ideas and practice of the popular Australian Jewish antifascist left in the 1940s and 1950s.

Read more: How COVID has shone a light on the ugly face of Australian antisemitism

A popular Jewish antifascist left-wing movement

In the 1940s and 1950s, I found, Holocaust memory was key to a popular Jewish antifascist discourse that was left-wing, non-nationalist and universalistic.

For these Jewish antifascists, memorialising the Holocaust meant fighting fascism and racism. These were seen as ongoing international threats that could only be defeated through solidarity with progressive forces and other oppressed people.

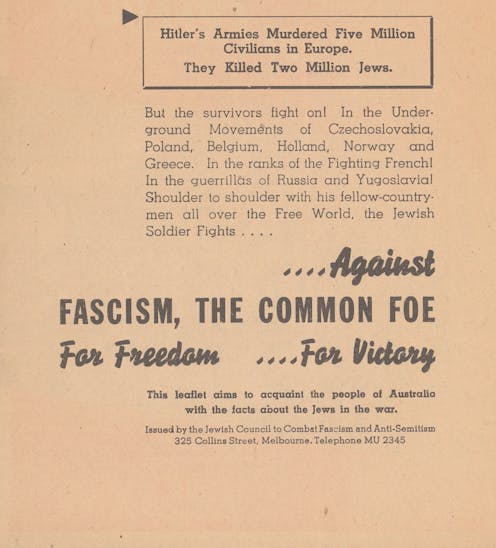

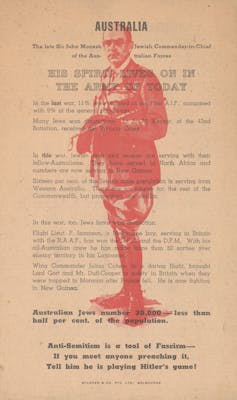

The main organisation of the Jewish antifascist left in Australia was the Jewish Council to Combat Fascism and Anti-Semitism, sometimes shortened to “the Jewish Council”.

Formed in Melbourne in 1942, the Jewish Council represented, in the words of historian David Rechter

in institutional form the broad-based antifascist leftism enjoying considerable vogue both within the Jewish community and in society at large.

It monitored and responded to incidents of antisemitism and actively linked the threats of antisemitism and fascism. Its strategy was to fight these threats by allying the Jewish community with progressive political forces.

By 1943 the Jewish Council was popular enough for the Victorian Jewish Advisory Board (the official representative body for Victorian Jewry) to vote to give it “full moral and financial support”. It was given responsibility for all official Jewish community public relations activities.

Throughout the 1940s, the Jewish Council had widespread support. It had hundreds of members and many committees (including special committees of doctors and lawyers and, later, a very active ladies auxiliary committee and youth section).

The philosophy and practice of the Jewish Council is summed up in a 1950 editorial in the popular Jewish left-wing magazine Unity, which warned that:

Goebbels’ spectre is still alive. Hitler’s lies and exploded theories are being refurbished.

It raised alarm about the widespread distribution of propaganda in Melbourne from a white supremacist organisation known as the “All Aryan World Movement”.

The editorial continued:

Shall we ignore such ridiculous and poisonous material? Some people in the community because of their sheltered lives in Australia have never really felt or understood the impact of Nazism on the Jewish people. They are advocates of silence. Their counterparts in Hitler’s Germany only learned the folly of their inactivity on the threshold of the gas chamber […] The spreading of fascist and anti-Semitic doctrines threatens us not only as Jews but strikes at the very foundations of our democracy.

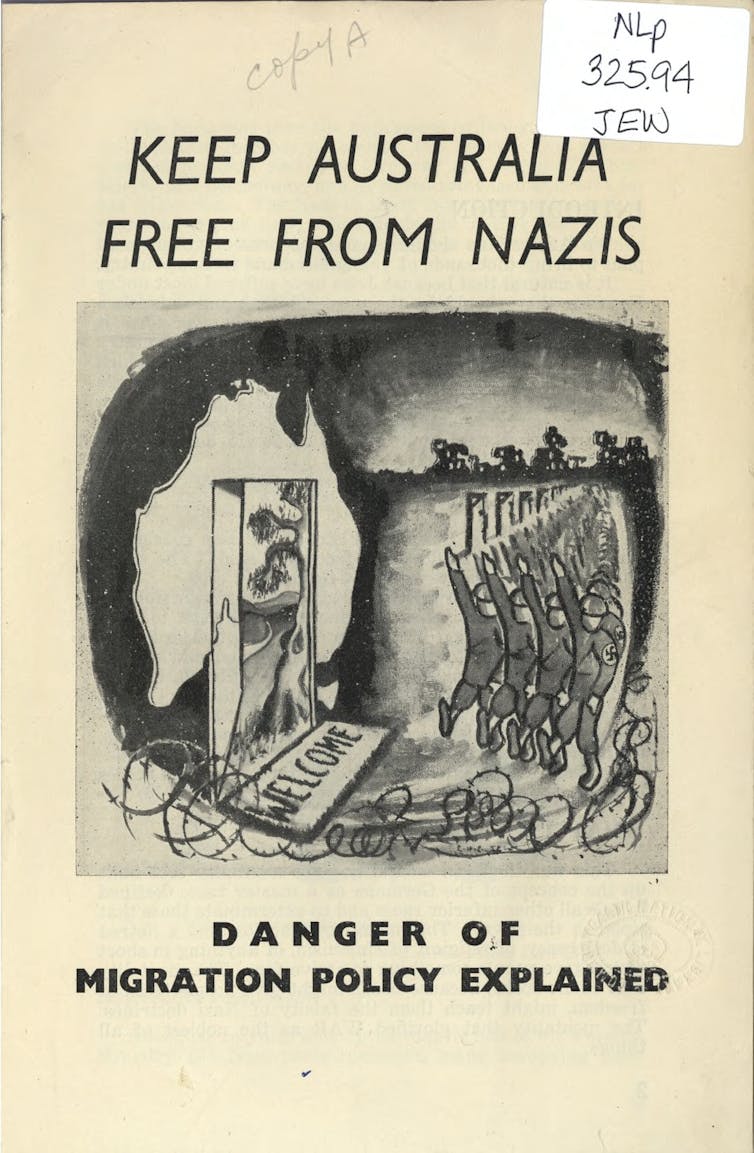

In the late 1940s, the Jewish Council was especially focused on the alarming numbers of Nazis and Nazi collaborators migrating to Australia under the Displaced Persons scheme.

Some were infamous Nazis and had harassed Jews in migrant reception centres.

In one dramatic incident of intelligence gathering, the Jewish Council’s Sam Goldbloom disguised himself as a plumber and sneaked into the shower block at the Bonegilla migrant reception centre. He photographed the scars under migrants’ left armpits, where they had removed their SS tattoos.

The broader fight against racism and colonialism

For the Jewish Council, the struggle against antisemitism was connected to fighting racism and colonialism more generally.

In 1947, during a period of persistent attack by the press and conservative forces on Jewish refugees, Jewish Council activist Norman Rothfield proclaimed:

We must attack reaction, no matter whence it comes. Dutch aggression against the Indonesia Republic is our concern, as is also the lynching of negroes [sic] in America, or the maltreatment of Aborigines [sic] in Australia […] We Jews can only be secure in a secure world. It is a world situation of conflict and strife together with a situation in Australia of intense class conflict which lays the ground for a campaign of anti-Semitic prejudice greater than any previous attacks in this country against a racial or religious minority.

The Jewish Council frequently compared the Holocaust with other instances of colonialism and racism.

A 1952 editorial from the Jewish Council-affiliated magazine The Clarion criticised Australia’s allies’ involvement in the Korean War, suggesting:

The Master Race theory of Nazism has reached a new peak in the war circles of America and Britain: for what is the difference between exterminating “Gooks” [sic] in Korea and “Yids” [sic] in Europe? Both are fruits from the same tree of evil.

Yosl Bergner, antifascist artist

The famous artist Yosl Bergner (1920-2017) presents another example of Jewish antifascist Holocaust memorialisation.

The war years saw the emergence of a new pan-Aboriginal movement led by Aboriginal activists Doug and Gladys Nicholls.

Bergner encountered this movement through Jewish antifascists and left cultural organisations, as well as his membership of the Communist Party of Australia.

He frequently painted urban Aboriginal people, rejecting the typical settler artist imagery of Aboriginal people as a “dying race”. Instead, his work depicts Aboriginal people as complex modern subjects, displaced and dispossessed in a world of urban poverty inseparable from the wider social relations of Australia.

In the mid-1940s, Bergner often exhibited these works along with his paintings of Polish Jews. He sought to suggest strong connections between the plight of the two oppressed peoples.

‘A Nazi Writes Home’

Another example is a short satirical story titled “A Nazi Writes Home”, written under the initials “L.F.” and published in Unity magazine in July 1951.

In this fictional letter of furious irony, a Nazi in Australia named “Fritz” writes his Nazi friend back in Germany.

He describes initially fearing Australia was “a spineless democracy-loving country, rotten with worship of the masses”. He changed his mind, however, after seeing how brutally Aboriginal people were treated. He goes on to celebrates Australia as an exemplary country of white supremacy – “the true Aryan theory”.

After seeing a white child racially abuse an older Aboriginal woman, Fritz suggested:

Australia is a land where the principles of National-Socialism are not altogether foreign.

The writer isn’t just drawing a clear link between the ongoing fascist threat and the racism of Australian colonialism. The story also links discrimination against Aboriginal people with the plight of Jews in the Holocaust and racial segregation laws in the United States.

“A Nazi Writes Home” places the oppression of Aboriginal people within an international antifascist context. It suggested antifascists needed to fight the entrenched structural racism of Australia.

Max Kaiser has received funding from the Commonwealth government for his PhD research.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.