'Eating food is our right. If our tongues aren't made of free will, it will be difficult to establish democracy. If we aren't allowed to eat our favourite food, how can we have desired politics?" said Asst Prof Chatichai Muksong, lecturer in history at Srinakharinwirot University, who has studied the topic of food for over two decades.

He and two other experts recently joined a public forum at Thai PBS to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the Siamese Revolution in 1932, which changed the political system from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy. Soon after, the government brought about a revolution in food to ensure that its citizens would be strong for the nation.

Chatichai said the Khana Ratsadon (People's Party) implemented a six-point programme -- independence, public safety, economic planning, equal rights, liberty and universal education -- during its 15-year tenure (until 1947). Pridi Banomyong, the intellectual leader of the group, drafted an outline economic plan in 1932, which caused conflict with King Prajadhipok (Rama VII).

"Following the counter-revolt by Prince Boworadet [the king's cousin], the king abdicated and the Khana Ratsadon began to enact economic reform. Luang Suwan Vajokkasikij, director-general of the Department of Agriculture, drew up agricultural and industrial plans. Accordingly, the government of Phraya Phahon Phonphayuhasena built the first white sugar plant in Lampang. Its products were transported to Bangkok by rail," he said.

In those days, white sugar was a luxury item imported from Java. Local people used palm, coconut and cane sugars. During the reign of King Nangklao (Rama III), Siam was a global exporter of sugar. When King Mongkut (Rama IV) signed the Bowring Treaty with Britain in 1855, Siam shifted its focus to the export of rice because its prices were going up.

"Phraya Phahon, the leader of senior military officers who joined the Khana Ratsadon and declared the end of the absolute monarchy, became prime minister from 1933-1938. He initiated the construction of the mill [in Koh Kha district] to reduce dependency on foreign sugar. It was home to a large number of sugar cane farms. His statue is erected in front of the plant," he said.

Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram, the founding member of the Khana Ratsadon, was attracted to the idea of a strong, militarised state. In 1939, his government issued ratthaniyom or state edicts to strengthen the country in the context of World War II. These measures included changing the country's name from Siam to Thailand and setting up rituals for national symbols, like an anthem and flag.

Chatichai said his government wanted to increase the population to 30-40 million and make them strong for the nation. It saw a high rate of fertility and mortality because mothers were not healthy. Dr Yong Chutima launched a national nutrition project to encourage the consumption of healthy food. For example, he promoted soybean, a source of protein, because it was affordable.

"Before the Siamese Revolution, locals ate too much rice with spicy and salty chilli paste, while those from middle and upper classes ate more delicate meals, according to Mae Krua Hua Pa [Thailand's first cookbook]. Dr Yong proposed the revolution in eating habits based on nutrition. He encouraged people to eat healthier and milder food," he said.

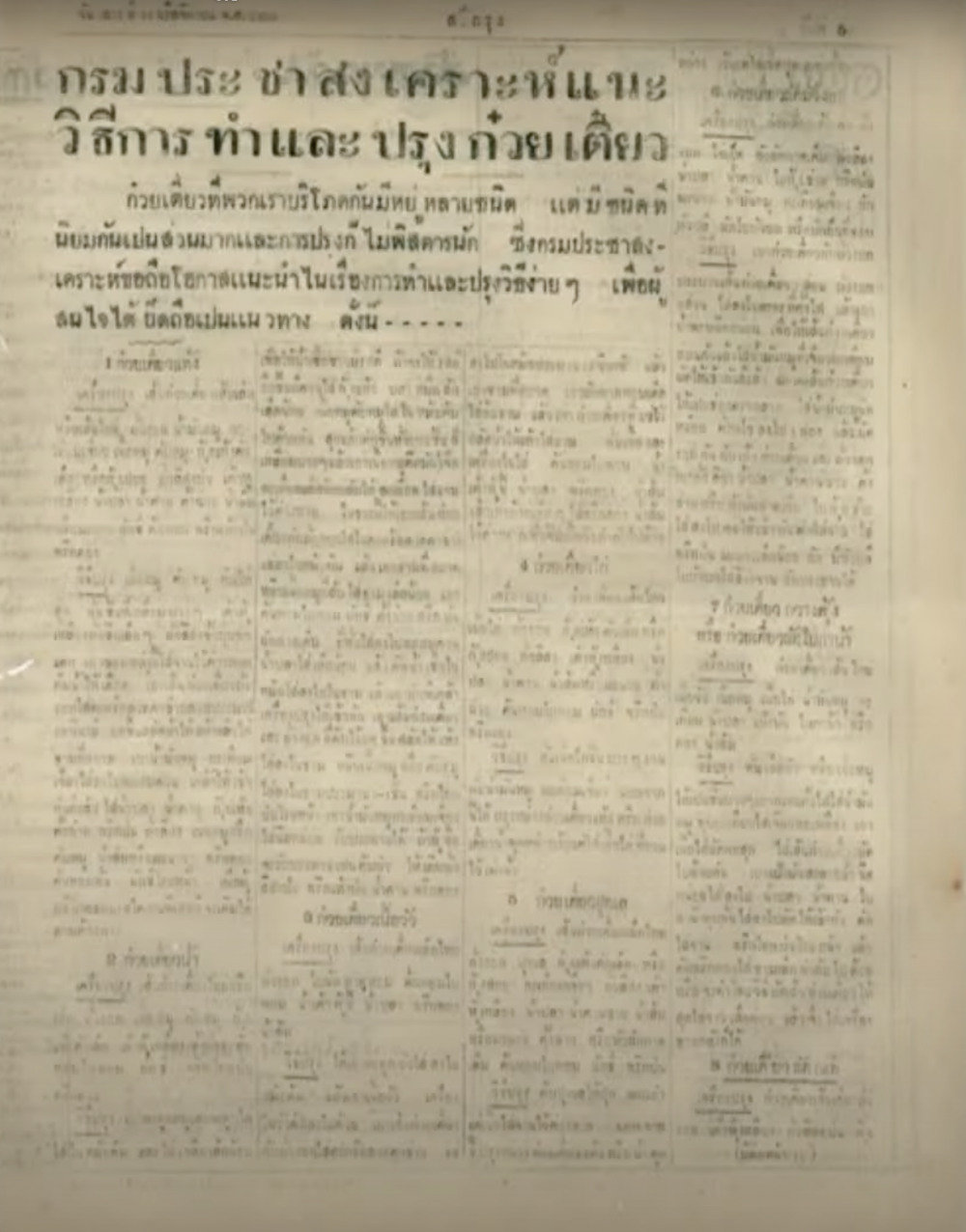

When flooding hit Bangkok in 1942, people were unable to do farm work. Chatichai said Phibun worried about their livelihood, recalling how his parents similarly suffered huge losses in 1917. He encouraged them to grow bean sprouts because they grow faster than rice. Then, he integrated industrial and agricultural policies into noodles, exclusive to the Chinese, and implemented supportive measures to create jobs.

"He gave each vendor a seed capital of 150 baht and told them to make a profit and return this sum of money to the government so that others would benefit from the scheme. He ordered government agencies to have noodle vendors on their premises. He also asked the Ministry of Interior to manufacture noodle groceries. He followed up on his work. You can see his handwritten comments on official documents," he said.

Chatichai said Phibun also gave subsidies for raising chickens to Luang Suwan. He was the first person to study chicken raising with a teacher in the Philippines. After the World War II, the US promoted it to increase its own social and cultural capital.

"It became a successful industry. He asked the Post and Telegraph Department to publish a slogan on a letter, which read 'an egg a day keeps a doctor away'. It was also broadcast on the radio. He encouraged people to drink coffee with soft-boiled eggs. Chicken meat and egg replaced pla thu [Thai short mackerel] as household staples," he said.

Next, the government planned to promote milk, a popular drink for foreigners only. Luang Suwan found that native cows produced a low level of milk, but foreign dairy cattle breeds were very expensive. During World War II, the government faced a shortage of milk and bought a piece of land for raising cows, which is now the location of Srinakharinwirot University.

"However, the war came to an end. Mom Luang Pin Malakul bought the land and founded the Advanced Teacher Training School [in 1949]. It was MR Chavanit Nadakorn Voravarn who brought in dairy cattle breeds. Milk drinking campaigns were successful. From my observation, Thais are taller than their neighbours, but this is not classification. Studies in other countries show that conscripts have obviously grown taller, but I am unable to get draft reports here," he said.

The Khana Ratsadon took the consumption of healthy food seriously to ensure that citizens would be strong enough for war and industrial work. Chatichai said it is the basic idea of the modern state in which the government collects tax from its citizens, but simultaneously looks after them. "It is mutual responsibility, not an act of kindness," he added.

After leafing through evidence from 1932-1957, he discovered legal documents banning the export of sugar after World War II and price gouging. In light of today's higher living costs, the government should not just ask for co-operation, but enforce laws to curb commodity prices. Meanwhile, people are now heavily dependent on external sources of food and energy.

"We can't produce food from scratch without infrastructure. A good country should have public space for gardening. For example, farm-to-table communities in the US help ensure their food security. Despite its capitalistic economy, they can provide chemical-free food and cut out the middleman. In 1997, our constitution endorsed public participation in health promotion, but green markets have disappeared," he said.