Many words we use come with hidden baggage. For instance we tend to assume that local, natural and grass-fed foods are good for our health, the environment and animal welfare, while intensive farming is bad for these things. However, the evidence often doesn’t bear this out.

Here are five terms about food which we need to use more precisely.

1. Local

Every environmentally-damaging activity is local to somewhere. However, many assume lower “food miles” always means “better for the environment”.

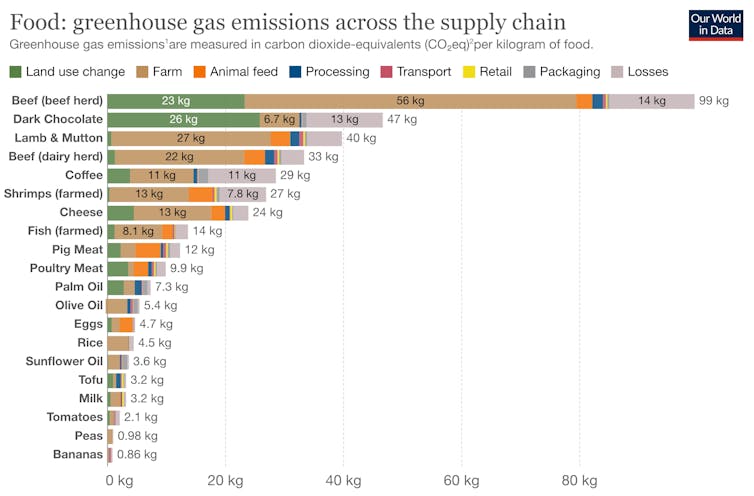

When it comes to greenhouse gas emissions, what you eat matters much more than where it’s come from. Although transport is a key sector for climate change, transporting food from farms to us (“food miles”) makes up on average only 6% of products’ total carbon footprint.

Very little food is air freighted, which has high emissions and should be avoided. Most travels by boat, rail and lorry, with much lower emissions per km. Of course, all other things being equal, fewer food miles means fewer emissions, and there are other reasons people might wish to purchase local produce.

Shifting how people travel matters much more than food miles. If you want to reduce emissions from transport, helping yourself and others cut out flying or taking the bus instead of driving will make a much bigger difference than not buying ship-freighted bananas.

2. Intensive

“Intensive” is rarely used in a positive context for farming. People tend to associate it with low animal welfare, pollution and faceless corporations.

But there are lots of different ways to farm intensively, and it is worth asking what sort of inputs are being referred to. Do we mean lots of human workers? High energy and electricity use? High fuel use? High pesticide use? Are we considering input levels in terms of per hectare, per tonne of produce, per 1,000 calories?

Many fruits, vegetables and other produce, from strawberries to mushrooms to vanilla, rely on manual labour for harvesting. However these types of produce are farmed, they are highly labour-intensive compared to arable crops which can be gathered by fewer people operating combine harvesters and tractors/trailers.

Organic crops are often used as an opposite example to “intensive” farms. They use fewer pesticides and so are less intensive in that respect. However, organic farming tends to have more intensive fuel and machinery use to mechanically break up weeds without herbicides, or extra human labour to control weeds manually.

Intensive farming is often used as shorthand for high-yield farming – that is, farming that produces more food per hectare. Land efficiency in food production is generally viewed positively. High yielding farm systems, with low pollution, soil loss and so on per tonne of produce, are arguably the main way we can feed the world with the least environmental damage.

The alternative to intensive high-yield farming is extensive low-yield farming, which ironically requires much more land. Land which could instead be used for reforestation, wetlands, solar or wind farms, housing or parks.

3. Industrial

Similar to “intensive”, this is almost universally used negatively with respect to animal welfare, sustainability and farming. The suggestion is that agriculture prior to the industrial revolution was always sustainable. But this is not the case.

Ancient and modern farming systems can both significantly damage the land and wild ecosystems. Farmers in the Roman empire seriously damaged their soils.

Norse settlers in Iceland deforested the landscape for their crops and livestock, which led to widespread loss of the island’s erosion-prone volcanic soils. These historic farming practices still affect the country’s ecology today.

4. Grass-fed

Grass-fed is generally viewed positively. However, grass-fed beef and lamb has a huge carbon and land footprint compared to pork, chicken and protein rich plants such as peas, beans and lentils.

In many countries most grass-fed livestock are also fed crops. This means the meat they produce can use more cropland – cropland alone, before even considering pasture land – per kilo than peas or beans.

5. Natural

Similar to local, “natural” is a friendly-sounding term which many assume means that food is good for us and for the planet. Natural is good. Unnatural is bad and, well, unnatural.

However, many natural foods are poisonous and dangerous. As the biologist Ottoline Leyser has pointed out, “No one sends their children into the woods saying ‘Eat anything you find. It’s all natural, so it must be good for you.’”

Meat is often viewed as more natural than vegan meat alternatives brewed in vats with a number of different ingredients. But modern livestock farming has involved millennia of artificial selection and is far from what most people would consider natural.

Animals are unable to move and form family and social bonds as they would in the wild. You won’t see a domestic cow or chicken in nature as they’d be eaten by predators in no time. These animals only exist because humans bred them into existence from less tasty and less manageable wild ancestors.

Meat alternatives – unnatural though they may be – generally have much smaller carbon and land footprints compared to meat. Unnatural can be better for nature.

So, the next time someone talks about intensive farming or natural food, ask them exactly what they mean.

Emma Garnett does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.