Suella Braverman has said that her role as home secretary “is first and foremost to be honest to the British people”, while making a series of misleading statements about English Channel crossings.

She conducted a series of media appearances on Wednesday morning to support the government’s new Illegal Migration Bill, which has ignited widespread opposition and practical questions about whether it could be implemented.

The UN Refugee Agency has said the creation of a legal duty to detain and deport all small boat asylum seekers without considering their claims would be a “clear breach” of international law.

The body said the proposals amount to an “asylum ban” and that branding refugees as undeserving based on their mode of travel “distorts fundamental facts”.

The government has admitted that the bill may also breach human rights laws, with the prime minister saying he was “up for the fight” predicted in British courts.

Here are some of the questionable claims made by the home secretary so far.

Safe and legal routes

Defending her plans on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, Ms Braverman argued that refugees did not need to cross the English Channel in small boats because there were alternative routes.

Asked how a 16-year-old orphan fleeing war or persecution in Africa would reach a sibling in the UK, the home secretary could not point to a “safe and legal route” that would apply.

She listed schemes including family reunion and community sponsorship, telling presenter Nick Robinson “you’re wrong” when he suggested none would apply to the hypothetical African teenager.

Ms Braverman hailed the welcoming of “hundreds of thousands of people”, but only in reference to bespoke schemes for Ukraine, Afghanistan and Hong Kong.

Home Office figures show that in 2022, 14 times more refugees were granted asylum after travelling to the UK themselves than were resettled by the British government.

Over 16,600 people were granted asylum after travelling to the UK and launching claims, while only 887 refugees were brought to the UK under the government’s flagship “UK Resettlement Scheme”.

A further 216 people were resettled under the separate Community Sponsorship Scheme, and 22 Afghans who missed the August 2021 evacuation were brought to Britain.

While 4,473 partners and children of refugees living in the UK were on family reunion visas, the figure is 40 per cent down on 2019 and the route is not open to siblings.

The figures do not include people arriving under schemes for Ukraine and Hong Kong, because they do not grant refugee status and do not amount to resettlement.

Ms Braverman said the government worked with the United Nations to select people for resettlement, but in a statement issued in response to the bill, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) said: “While critical, resettlement schemes remain very limited, and can never substitute for access to asylum.

“The Refugee Convention explicitly recognises that refugees may be compelled to enter a country of asylum irregularly.”

‘First safe country’

A core assertion underpinning the government policy is that refugees should claim asylum “in the first safe country they reach”.

“If people are coming here from a safe country, they really should not be claiming asylum in the first place,” Ms Braverman told MPs on Tuesday.

But the UNHCR said: “International law does not require that refugees claim asylum in the first country they reach.”

In a previous statement, the body said that the principle would cause the “collapse” of the global refugee system if followed, with the countries neighbouring conflict zones already hosting the vast majority of displaced people.

“If all refugees were obliged to remain in the first safe country they encountered, the whole system would probably collapse,” the UNHCR said in 2021.

“The countries closer to zones of conflict and displacement would be totally overwhelmed, while countries further removed would share little or none of the responsibility. This would hardly be fair, or workable, and runs against the spirit of the Refugee Convention.”

The new laws will be a ‘deterrent’

Ms Braverman told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme: “The running theme throughout this bill is deterrence.

“We want to ensure that people understand they shouldn’t make the journey in the first place because they will be removed if they do so. That will stop the people-smuggling gangs … deterrence is a big objective for these measures.”

When The Independent asked the Home Office for research or evidence to support those claims, officials were unable to provide any.

During a press conference on Tuesday, Rishi Sunak pointed only to a single anecdote from a Conservative MP, who told parliament he heard that the announcement of the Rwanda scheme caused a “big upsurge in migrants in France approaching authorities asking about staying in France”.

The prime minister claimed: “The deterrent effect can be quite powerful quite quickly.”

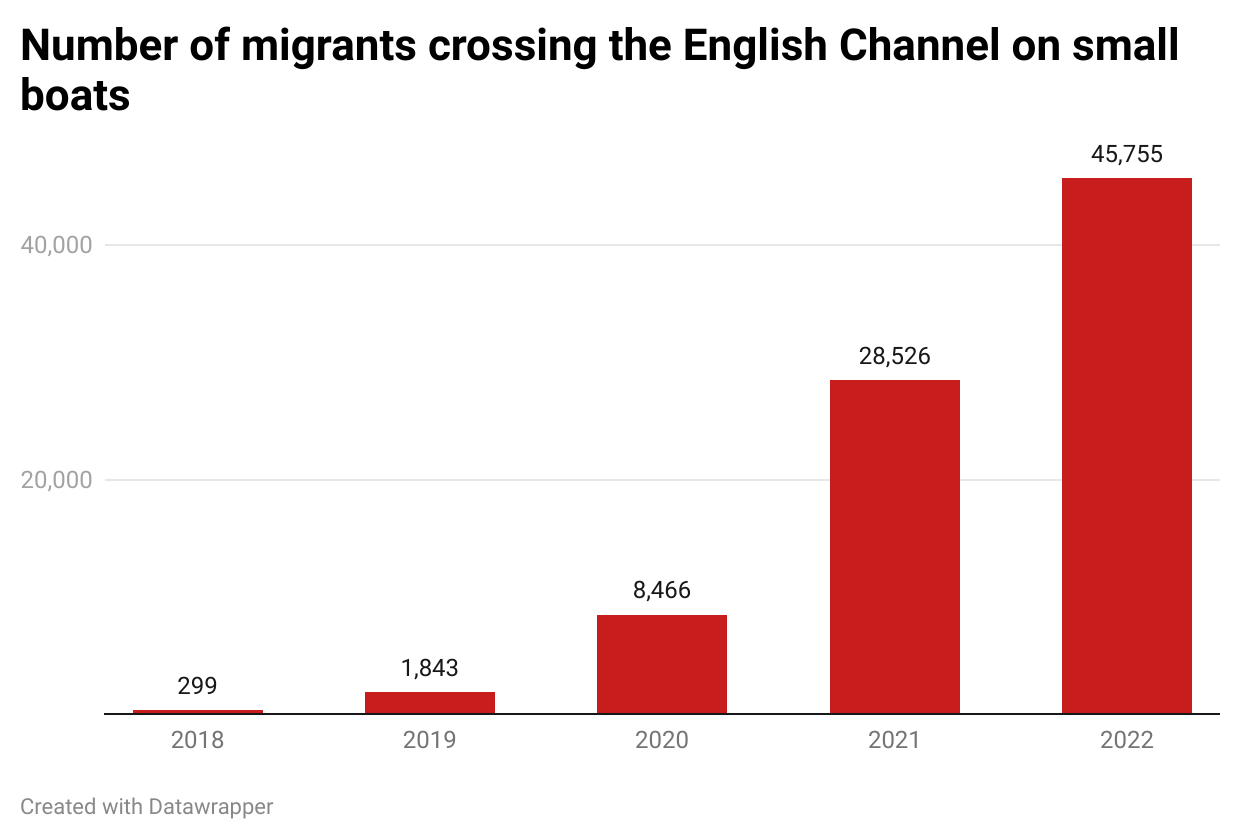

Successive governments have claimed that a series of policies regarding Channel crossings would be a deterrent, but numbers have continued to rocket since 2018.

Previous alleged deterrents include Royal Navy patrols, the Rwanda scheme and last year’s Nationality and Borders Act. None have caused any tangible reduction in crossings.

‘Necessary, proportionate and humanitarian’

Ms Braverman told the BBC that the new Illegal Migration Bill was a “necessary, proportionate and humanitarian” means of reducing crossings.

But the government has ignored or dismissed a series of alternative solutions proposed by parliamentary committees, the UN and expert groups.

On Tuesday, the UNHCR said it had “presented the UK government with concrete and actionable proposals”.

“Making the asylum system work is key to tackling this challenge,” a statement added. “Fast, fair and efficient case processing, as well as enhanced reception conditions, would accelerate the integration of those found to be refugees and facilitate the swift return of those who have no legal basis to stay.”

Government policies and processing rates have caused the asylum backlog to rise to a record of over 160,000 people awaiting an initial decision, many for years.

The chair of parliament’s Home Affairs Committee, Dame Diana Johnson, told parliament that an inquiry last year had called for the government to “expand safe and legal routes and negotiate a returns policy with the EU”.

It has done neither, and last April the government voted down a law that would have increased the number of refugees resettled directly from outside Europe, and expanded family reunion schemes to allow asylum seekers to join relatives in the UK more easily without resorting to dangerous journeys.

Previous ministers have rejected the idea of allowing initial asylum processing in France, so that those with a legitimate claim can legally board safe transport, and a 2021 watchdog report said the government had not “monitored or evaluated the impact of its policies”.

In November 2020, the Independent Chief Inspectorate of Borders and Immigration said Home Office officials admitted that small boats arose “as a consequence of the success of the extensive work done by the UK and its European partners, in particular the French, in making other methods of illegal entry more difficult”.

The rise had been predicted by parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee in 2019, with a report warning: “The UK cannot expect others to prevent Channel crossing attempts if we are not willing to work together to address the root causes.

“A policy that focuses exclusively on closing borders will drive migrants to take more dangerous routes, and push them into the hands of criminal groups.”

100 million people

The home secretary has repeatedly claimed that without reform, “[there are] 100 million people around the world who could qualify for protection under our current laws”.

She told ITV’s Good Morning Britain the figure was “an estimate by the UN”, adding: “Many of them are heading to the United Kingdom.”

Ms Braverman was challenged on whether anywhere near that number of people would ever attempt to reach Britain, when 83,000 have arrived on small boats since 2018.

“On what planet is that likely and how is that not inflammatory language?” asked host Susanna Reid.

While the UNHCR has estimated that there are more than 100 million forcibly displaced people around the world, only 26 million have left their own country and most of those are in the countries immediately surrounding conflict zones.